- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- within Intellectual Property, Transport, Media, Telecoms, IT and Entertainment topic(s)

- with Inhouse Counsel

- with readers working within the Law Firm industries

Last week the Court of Appeal handed down its judgment in Accord and others v Astellas and another. The patent protects the prostate cancer drug called Xtandi (enzalutamide), which had global sales of over $5 billion in 2023. The generic parties sought to revoke EP 1 893 196 covering the compound, but were unsuccessful at first instance and now on appeal. The decision tells a cautionary tale about how to conduct revocation actions based on obviousness in the UK.

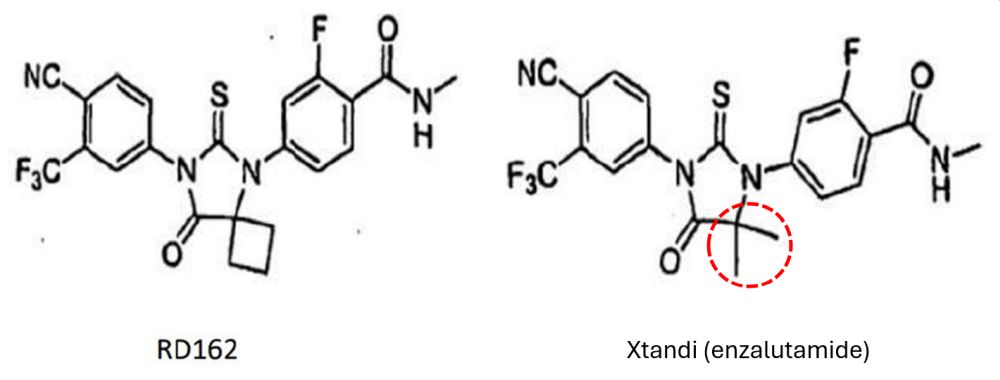

The generics relied on two related pieces of prior art (slides and a poster from a conference in late 2005), which disclose a closely related molecule called RD162. Enzalutamide only differs from RD162 by the substituent at one carbon atom ("position X") as you can see below. The trial judge (Mellor J) did not agree that the modification to RD162 was obvious based on the prior art: in summary, he found that the generics' case depended on hindsight and lacked a concrete factual scenario explaining why the team would change position X into enzalutamide.

Obviousness

The ultimate test for this ground of revocation in the UK is, as the name suggests, whether the claim is obvious over the cited prior art. There are various guiding principles that may assist in the assessment, but they are not a substitute. The degree of modification over the prior art – in this case, just one CH2 moiety – is not relevant. A change can be 'small', but that does not make it immaterial. Conversely, motivation may be a relevant consideration, although it is not a necessary precondition for obviousness. This became an important part of the case, as discussed further below.

The conduct of structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies

The thrust of the generics' case was that it would have been obvious for the skilled person (here, a medicinal chemist) to do SAR on RD162, and these routine studies would have led the skilled person to enzalutamide. However, in evidence, the generics' expert did not explain why the skilled person would have been motivated to modify position X. The expert was instructed to consider the change at that position, and asked whether it would have a material effect. The trial judge found that this tainted his evidence with hindsight. The generics had failed to properly advance a case (which may have been successful) that the skilled person, looking at RD162, would have explored a change to position X, for example, in order to fully characterise the activity of the molecule, to develop an improved compound, or to develop a novel compound.

Ultimately, the trial judge said that the generics came "very close to succeeding", but they failed because the reason for deviating from RD162 was not properly advanced in the evidence in chief (as opposed to at trial and through skilful cross-examination).

Appeal decision

It is notoriously difficult to overturn a finding on obviousness as it is a factual assessment, and appeals can only be made on an error of law or principle. The generics' appeal concerned whether or not, by criticising the missing context / scenario for the inventive step analysis, the trial judge erred in law.

Arnold LJ, with whom the others agreed, found that a key issue was the failure of the generics' expert to explain what objective the skilled person had in mind when developing an alternative to RD162. A very different position could have been reached had the expert for example said, in evidence, that the skilled person would have been interested in characterising RD162 by modifying parts of the compound, in order to understand what contributed to activity (and this would have included modifying position X). His Lordship thought that the trial judge was correct to consider this deficiency.

Importantly for the future, Arnold LJ questioned whether a party revoking a patent should have its expert follow the so-called Pozzoli approach, as this can create a risk of hindsight. This approach, which was followed by the generics' expert, asks them to consider if the difference between the claim and the prior art was obvious – the problem being that it asks the expert to consider the problem by reference to its solution. Instead, and quoting from paragraph [98] of the appeal judgment, his Lordship said that "Hindsight would have been easier to avoid if [the generics' expert] had been asked an open question along the following lines: supposing that the skilled team, after having read the Poster, wanted to develop an alternative to RD162 which had similar therapeutic potential, what compound(s) would have been obvious choices to investigate?"

Take-aways

Although his Lordship resisted setting a prescriptive formula above, his phrasing of the question shows the importance of telling a credible story when attempting to revoke a patent based on obviousness – and avoiding the use of the Pozzoli approach. This story should answer, in evidence, what real world scenario would lead the skilled team to make the modification from the prior art. It is not enough to assert that the change is trivial – the evidence must show that the skilled team would reach that compound because of, for example, routine SAR studies.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]