- within Tax topic(s)

- in European Union

- within Wealth Management topic(s)

- in European Union

In this second article in the 'Killing trusts softly'

series, Marsha Laine Dungog, Jennifer S. Silvius and David Laanemaa discuss

the evolving US tax treatment faced by Australian superannuation

funds for US persons and Aussie investors alike.

You can also read part 1, Killing trusts softly: The Australia-Canada-US

trust paradox.

This article was first published in Tax Notes International, Volume 120, Number 1, on October 6, 2025.

Nine months have passed, and Australia has yet to hit its stride when it comes to relations with the United States.

It started in January, when U.S. tennis player Madison Keyes won her first singles championship at the Australian Open, in Melbourne. Even though Australians won the mixed-doubles category, this singular grand slam win foreshadowed the next nine months of U.S.- Australia relations. Indeed, over the past few months, the United States has unilaterally embarked on changing the course of international world trade without the usual diplomatic courtesies and formalities traditionally afforded to trusted allies, including Australia.

Opening volley

On February 1 President Trump issued three executive orders1 imposing heavy tariffs on Mexico, Canada, and China, showing that it was not in fact business as usual in Washington. Then on April 2 Trump issued Executive Order 14257, which sought to recalibrate the ongoing trade imbalance between the United States and the rest of the world by introducing tariffs on an unprecedented scale not attempted by any sitting U.S. president since Woodrow Wilson.2]

Hashtagged #liberationday, EO 14257 literally threw the baby out with the bathwater where U.S.- Australia relations are concerned, causing Aussies to wonder if 100 years of mateship3 between these two great countries could be past its prime. Just five weeks earlier, Australian Treasury Secretary Jim Chalmers, in his keynote speech at the U.S. Superannuation Investment Summit,4 said that the four-day event was timely and a powerful demonstration of the strategic and economic alignment of the two countries that has done so much to secure prosperity for both peoples.5 U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent even attended and endorsed Australia's "fantastic" superannuation system that has delivered growth of Australian retirement savings in a "sustainable" and "regular" way.6] Chalmers and Bessent spoke gospel truth — the glowing track record of Australian pension fund investments in the United States speaks for itself. In 2025 the United States has attracted over one third of all private market investments that Australian pension funds make overseas,7 notably in U.S. private equities, real estate, and infrastructure.

However, has the imposition of tariffs8 on Australia's beef industry broken the spell cast by the summit over key superannuation industry players9 who came to Washington and publicly acknowledged their intent to invest trillions10 of super fund dollars in the U.S. economy? For Australia, the summit was about becoming the trade partner of choice for the United States for its long-term capital needs.11 Dangling its behemoth super fund war chest before the Trump administration was a calculated proposition to bring to the forefront Australia's privatized social security system as a safe and reliable provider of long-term capital to the United States with projected growth to make it the second-largest pension fund market globally by 2030.12 More recently, however, Australia's top super funds are reducing their exposure to U.S. equities because of stretched valuations and increased volatility caused by recent Trump administration policies,13] opting instead to invest in alternative assets such as private equity,14 insurance bonds, and asset backed financing, as well as emerging markets in China. They are also diversifying their portfolios to cope with geopolitical uncertainty,15 with some investing in real estate assets, property, and infrastructure, while others are exploring opportunities in Europe and India.16]

Still, now that the infamous revenge tax17 has been shelved, the Aussie appetite for U.S. capital markets has once more been somewhat revived.18 One has to ask why Australian super funds are so hell-bent on pursuing U.S. opportunities19 when the U.S. tax system, even without the revenge tax, has subjected many U.S. and Aussie expats to premature U.S. taxation on super fund savings that have not even matured.20 According to a new report, Australia's pension fund investment in the United States is expected to more than double over the next decade from US $400 billion to over US $1 trillion.21 Considering the Australian pension system is greater than that of the largest sovereign wealth funds,22 and on track to surpass Canada and the United Kingdom to become the world's second-largest retirement system by 2031,23 the exciting possibility of Australia's becoming the key investment partner of the United States mandates a stricter review of exactly how these super funds are going to be classified and taxed under the U.S. tax regime. In this second installment, Dungog and Silvius collaborated with David Laanemaa,24 a cross-border Australian tax director at Bentleys Pty Ltd, New South Wales, in their attempt to answer whether the U.S.-Australia mateship can have a happily ever after in light of current U.S. tax treatment of Australian superannuation funds, and what it would take for the United States to be truly a safe and successful investment location for Australians.25]

Australian superannuation funds on the down low

The superannuation industry is a significant player in the Australian retirement scheme, with superannuation assets totaling AUD 4.1 trillion at the end of the March 2025 quarter,26 and with significant growth in pension mandates coming from listed equities, global fixed interest, and private credit.27 Almost half of this total is invested in assets outside Australia, primarily listed international equities.28 Technically, there are six types of super funds available to Australians: industry funds, corporate funds,29 retail funds, public sector funds, self-managed superannuation funds (SMSFs), and small Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) funds. However, the real distinction is not with the type of super fund, but rather, the category — whether the specific super fund is a large professional public offer fund or a small offer fund, which is a do-it-yourself fund among partners and private families.

Except for SMSFs, which are regulated by the Australian Taxation Office,30 and government funds, which are operated by some Australian states and have constitutional exemptions, it is APRA that manages all larger professional super funds.31 These large professional public offer super funds must have trustees that hold registrable superannuation entities (RSE) licenses.32 To date, RSE licensees are approximately just 5933 and are regulated by APRA and the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) for prudential and consumer protection purposes.

As of September 2024, there were 95 public offer super funds,34 which can be further divided into industry and retail funds. Industry funds are not for profit and have equal representation of unions and employers (with some independents on their boards). They are linked through common ownership of IFM Investors and have their own representative body, the Super Members Council.35 The retail funds are for-profit, owned by banks, insurers, financial services business and investment firms with a different representative body, and the Financial Services Council.36 Retail fund members run platform products with lots of choice, not just a few investment options, and tend to be subject to professional financial advice.

In contrast to smaller funds and larger public offer funds, SMSFs are not regulated by APRA or ASIC because the members of SMSFs are also statutorily required to be trustees of the funds. SMSFs are regulated by the ATO and must be in strict compliance with tax law requirements on superannuation to remain subject to preferential tax rates. Most SMSFs are serviced by accounting firms and are represented by the SMSF Association.37

As of May the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia38 (ASFA) reported that industry funds have the most substantial assets under management, equivalent to AUD 1.485 billion spread among 20 funds, followed by small APRA funds with AUD 1.003 billion under management across 646,847 funds.39 Altogether, the industry funds — so called because they initially were created for workers in specific economic sectors — hold more than one-third of the country's retirement savings.40 Separately, SMSF assets total AUD 1.005 billion,41 which is spread over 646,168 privately managed funds and covers 1.14 million members.42]

As of June 30, APRA reported the following key statistics for the superannuation industry43:

- Total superannuation assets increased by 4.8 percent over the quarter to AUD 4.3 trillion as of June 30, of which AUD 3 trillion was in APRA-regulated funds.

- Total contributions increased by 14.1 percent to AUD 210.2 billion in the year ending June 30. Employer contributions increased by 10.1 percent over the year to AUD 151.1 billion. Member contributions increased by 25.8 percent over the year to 59.1 billion.

- Benefit payments increased by 12.8 percent to AUD 132.5 billion in the year ending June 30. This increase was the result of lump-sum payments rising by 14.3 percent to AUD 73.3 billion and pension payments increasing by 11 percent to AUD 59.2 billion.

These statistics confirm what was already apparent, that the Australian super fund war chest is massive and growing exponentially. And it is heading our way. The question is, are we ready?

From an Australian perspective, super funds are statutory trusts because each is created under the superannuation laws44 that mandate that employers create trusts providing for employees' retirement. Employers are legally obligated to make superannuation contributions based on 12 percent pretax earnings of each employee to a complying superannuation fund (either APRAregulated or SMSF). Employers who do not follow this requirement are subject to a penalty tax. Unless self-employed, employees can choose the fund to which their employer contributions are paid. If the employee doesn't choose a fund, the contributions are invested in a MySuper, which is a low-fee default plan.45 However, employees cannot opt out of paying super contributions, although they can make additional voluntary contributions (either pretax or posttax) up to annual contribution caps. They benefit from lower tax rates on contributions46 and earnings of the funds.47] Income distributions are tax free in retirement.

To encourage contributions, these funds receive preferentially low tax rates in Australia, with the aim of increasing private savings and facilitating asset growth. Unlike traditional retirement funds, contributions and earnings generated by investments held by a super fund are taxed at a low flat rate of 15 percent.48 Broadly, where a super fund has derived a capital gain from the disposal of an asset, any net capital gain, after deducting any capital losses, will be included in the fund's taxable income and will attract tax of 15 percent, which may be further reduced to 10 percent.49 Contributions and earnings in a super fund account cannot be accessed by the beneficial owner, the employee, until a condition of release is met — reaching age 65 or retirement. At that time, distributions from the super fund are generally tax free.50]

The Australian government highly encourages investment in a super fund to increase the level of savings for an individual's retirement. It provides incentives for saving funds in a super, such as current tax concessions, which serve the dual purpose of encouraging future savings and ensuring the beneficiaries are compensated because assets placed in a super fund cannot be accessed until retirement. Preferential tax rates encourage fund owners to contribute and engage in active investments that will grow the assets. These investments range from bonds and equities to partnership interests in active business operations. In this regard, SMSFs are the super fund of choice for these types of undertakings.

However, for U.S. taxpayers, using super funds to actively invest and hold business and real estate assets creates a unique challenge — because U.S. tax laws are also applied to determine the treatment of the super fund, and as a corollary, income and gains generated by its underlying assets, the results are often incongruent with and adverse to the preferential tax treatment applied in Australia. Thus, an Australian's investment in a super, which is the third pillar in Australia's retirement system,51 could be at risk in the United States depending on its classification.

When superannuation reforms were enacted in 2017,52 Australia's legislature made clear its intent to continue providing tax-favored treatment for supers so that they would eventually replace money paid out of the old age pension funded by government. In short, one could say it is almost Australian social security.

Recent Division 296 reforms in Australia

These days, however, the super fund industry has become a victim of its meteoric success. The super fund is no longer perceived as a savings vehicle for a dignified retirement, alongside government support, in an equitable and sustainable way. Over the past 30 years since super funds took off, the superannuation regime has received wide criticism from all corners as the focus has shifted from savings to tax sheltering because people have been hoarding money in taxconcessional superannuations for family wealth.53 Over the last few years, Australia's Labor Party has tried to impose a super tax. Super funds with accumulated balances over AUD 3 million are set to be levied a tax on unrealized capital gains over that amount. This proposed tax is intended to force people to consider shifting wealth from super funds to other vehicles such as family trusts and investment companies. The fate of the unrealized capital gains tax is yet to be decided but will likely become law.

Pension plans around the world

Australia's reintroduction of the super regime in 1992 was followed by other countries that also instituted pension reforms to increase savings for their aging populations. Currently, many types of retirement savings plans54 exist worldwide that make up the cross-border pension landscape. However, there is no comprehensive scheme providing a uniform global classification of these plans for all tax purposes in all countries.

In general, pension plans around the world have shifted to fully funded private individual accounts that can be accessed by individuals through their employers, by social partners (occupational pensions), or directly without any involvement by their employers and established by a pension fund or a financial institution acting as a pension provider (personal pensions). Occupational pensions are either defined benefit (DB) or defined contribution (DC). In DC plans, benefits offered are directly linked to the extent of contributions made by the participants, but participants bear the brunt of the risk and are responsible for managing their investment decisions for retirement. In contrast, in traditional DB plans sponsoring employers assume all risks. However, some countries have developed hybrid DB plans, which come in different forms but all result in spreading the risks between employers and employees. Both types of pensions coexist in 33 out of the 38 countries appearing in the OECD report.55

According to the OECD, DC plans and personal pensions have been gaining prominence at the expense of DB plans even in countries in which there has historically been a high proportion of assets in DB plans, such as the United States.56 Indeed, this same observation can be found in the August 2022 report on retirement security57 by the U.S. Government Accountability Office. It notes that traditional DB pensions have become less common, with more individuals managing their own retirement savings. Since the 1980s many OECD countries instituted reforms to restructure their public pension programs to address anticipated financial shortfalls in the traditional pay-as-you-go system,58 which meant reducing benefits under the public pension and increasing incentives for fully funded and mandatory individual account-based savings59 (fully funded private pension plans).60 This included:

- requiring automatic enrollment by employers of their employees in retirement savings plans to increase program participation;61]

- making employer contributions and government contributions mandatory to encourage participants to remain in their plans;62

- using default contribution rates of 3 percent to 5 percent of a participant's salary to facilitate savings by simplifying key investment decisions of how much to contribute;63 and

- providing participants with flexibility in terms of plan options when changing employers, ability to pause or stop contributions, ability to take early withdrawals, and ability to draw down funds.64]

Fully funded private pension plans are intended to complement existing public pension plans, so much so that in some countries, like Australia, Canada, Chile, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, funded private pension plans have overtaken public pensions as the main source of retirement funding.65]

With more and more U.S. persons relocating abroad for work and lifestyle choices, it is not a surprise that many now participate in foreign fully funded private pension plans that do not fit squarely within the four corners of what would be classified as a tax-qualified plan under the U.S. tax code.66 Not surprisingly, the foreign countries to which U.S. persons are relocating are among the top-ranked for fully funded private pension plan assets as of 2022. These are: the United Kingdom (US $3.6 trillion), Australia (US $2.3 trillion), the Netherlands (US $2 trillion), Canada (US $1.7 trillion), Japan (US $1.5 trillion), and Switzerland (US $1.2 trillion).67

A super-sized lack of guidance

Of the foregoing countries, only Canada has received adequate guidance from the IRS over U.S. tax classification, tax treatment, and reporting requirements of its various pension and savings plans over the last two decades.68 Australian super funds continue to receive inconsistent tax classification and treatment, and although Australia initially hoped that the U.S. Tax Court in Dixon69 would be able to provide much-needed direction, that is looking less and less likely. As of the time of writing of this article, the Dixon case has been languishing in the Tax Court for over five years.

Similarly, the international tax community hoped that Australian super funds would come back to the forefront with the January 2024 indictment of John Anthony Castro in the Northern District of Texas. Castro was indicted on and ultimately convicted of 33 separate counts of assisting in the preparation of a fraudulent tax return, based on his activities while operating Castro & Co. LLC, a virtual tax preparation business with locations in Orlando, Florida; Mansfield, Texas; and Washington, D.C.70 One group of particular interest to Castro and his company was Australian and American expats, especially those with significant accumulations in their super funds not previously disclosed on U.S. tax returns.

Since 2016 Castro had been holding himself out as an international tax expert and participated in the preparation of more than 1,900 tax returns for U.S. taxpayers around the world. Unfortunately for his many clients, he was actually preparing tax returns based on fraudulent positions and novel legal theories not supported by U.S. tax law.71 Most significantly for our purposes, Castro was a proponent of the theory that interests in Australian super funds should be classified as interests in "privatized social security accounts" and therefore exempted from U.S. taxation entirely under article 18(2) of the Australia-U.S. tax treaty.72 On this basis, he sold U.S. tax opinions to Aussie and American expats with undisclosed super funds, advising them on how to exempt their super fund earnings and distributions from U.S. income tax. Included in his client list was the aforementioned Daryl Dixon, who became his client sometime in 2016.73

Because of this connection, when Castro was indicted, the international tax community hoped that there would finally be some additional guidance forthcoming from the U.S. Treasury on the proper U.S. tax classification of a super fund. But alas, it was not meant to be. Castro's domestic activities related to fraudulent deductions, refunds, and filings were so prolific that the assistant U.S. attorneys prosecuting the case were able to obtain a conviction without even really having to rely on litigating the super fund issue. So we continue to wait.

Isolationist tendencies run deep

Unsurprising? Perhaps. Indeed, international tax practitioners have long bemoaned the fact that the U.S. domestic tax regime has not kept pace with pension reforms initiated around the world to expand retirement security by increasing opportunities for individual taxpayers to accumulate pretax savings. Perhaps the better view is that the United States has never really been interested in catching up with the latest international trends. Being oblivious to the changing world views on taxation of retirement and pensions (which sacrifices tax revenue to encourage personal savings among the population), the current U.S. statutory tax framework for classification and reporting of foreign retirement savings plans remains incoherent and disjointed, severely lacking a uniform structure for addressing foreign pension plan arrangements in a manner that extends to such plans the benefits of tax deferral or, in some cases outright exemption, as endeavored in U.S. bilateral tax treaties. To further complicate this area of the law, in May 2018 the IRS implemented an enforcement campaign targeting foreign trust reporting by U.S. persons. This campaign unfortunately cast a broad net, entangling U.S. persons with beneficial interests in cross-border pension plans.

Taken together, perhaps this all helps to explain why many Australians remain generally perplexed and astounded by the U.S. tax classification and treatment of a super fund. First, the United States taxes contributions, earnings, and distributions from a super simply because the beneficiary of that super is American. Then, the United States taxes a super fund's investment in U.S.-situs assets (including investments in real estate, U.S. startup companies, and other businesses) not as assets held in a foreign pension fund, which are often subject to deferral or preferential rates, but as any other foreign investor, subject to U.S. withholding taxes and standard marginal rates.

U.S. pensions: an overview

Over the past 100 years,74 in the United States at least, a survey of publications by Treasury and the IRS yields a plethora of guidance on the tax treatment of domestic retirement plans, and more recently, foreign pension plans. Published guidance on the former appears to have been issued on an as-needed basis, resulting in the application of provisions under the code with the related Treasury regulations that, when strung together, provide a tax classification that supports adverse tax treatment of the foreign plan for U.S. income tax purposes. Indeed, relief from unfavorable tax consequences for U.S. participants in foreign plans has been sought time and again through applicable treaty provisions negotiated with the United States.75 Because of the inherent political nature of the treaty-making process, the ratification and amendment of tax treaties remains in a lengthy hiatus,76 subject to the changing priorities of the U.S. government. The United States must urgently acknowledge the evolving nature of foreign pension plans and adapt existing domestic tax frameworks to keep pace with these changes, so that U.S. persons with beneficial interests in these plans are not disadvantaged, and to keep the country competitive with the rest of the world. The U.S. retirement scheme allows for individuals to direct their savings and to have both occupational and personal pensions. However, unlike many other countries, occupational plans were voluntary in the United States until the recent passage of the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act 2.0 of 2022,77 which recalibrates traditional U.S. domestic retirement vehicles (such as section 401(k) plans and individual retirement accounts) one step closer to the pension and retirement regimes of other countries with mandatory employer-funded accounts.

Because the U.S. retirement regime for occupational pensions up until the SECURE Act was voluntary, accounts established by an employer under a DC or DB plan for the benefit of its employees to assist with retirement savings are afforded tax-deferred status under section 401(a) to encourage participation. This statute confers tax-qualified treatment to an employees' trust that is created or organized in the United States and forms part of a stock bonus, pension, or profit sharing plan of an employer for the benefit of its employees or beneficiaries. The irony is that there is no definition under the code or regulations of what would constitute an employees' trust for this purpose. Moreover, even if one were somehow able to divine that a particular retirement or pension plan is an employees' trust, it would still most definitely have to be a domestic trust to obtain tax-qualified status under section 401(a). The tax-deferral benefits enjoyed by a U.S. employee who is covered under a U.S. tax qualified plan extends even after that employee relocates to work in another country. However, a U.S. participant's contributions to such a plan, as well as income accruals and distributions from the U.S. plan, are generally subject to tax in the other country unless relief is available under the applicable tax treaty between the United States and that country.78 Our survey of existing U.S. tax treaties with applicable relief provisions reveals that there is no uniformity of relief to be found.79

Robbing immigrants of their savings?

Nonresident persons who relocate to the United States and participate in U.S. plans are afforded the same tax-deferral benefits on plan contributions and income accruals as U.S. persons. However, while there is a U.S. taxation exemption option, under section 72(w),80 for any contributions made to an existing foreign retirement plan before relocating to the United States, there does not appear to be any relief from current U.S. taxation of foreign employer contributions made to the foreign plan, as well as income and gains accrued in the foreign plan (from both foreign employer and employee contributions) once the beneficiary of the plan has become a U.S. tax resident.81 The result is that a substantial portion of the corpus and all of the income and gains accrued in the plan become subject to U.S. taxation once the conditions are satisfied for penalty-free withdrawals and distributions to commence.

In the same vein, U.S. persons who participate in another country's foreign retirement and savings plans while living overseas have very limited ability to claim tax deferral on contributions, income accruals, and distributions from such plans that are not U.S. tax-qualified plans. As noted, most foreign plans will not meet the requirements for U.S. tax-qualified plans under section 401(a) because there is no definition in the code of employees' trust, and even if there were, section 501(a) requires an employees' trust to be a U.S. domestic trust.82 Hence, the U.S. tax treatment of foreign plans falls under section 402(b), which was enacted in its current form in 196983 to govern contributions and earnings made within a nonexempt employees' trust. This default treatment of foreign plans owned by U.S. persons has an adverse effect on the ability of U.S. persons to accumulate savings compared with non-U.S. persons, as well as arguably a chilling effect on the ability of the United States to attract and retain the best and most talented workers in the world.

Section 402(b) provides that (1) contributions made to the foreign plan by a foreign employer would be includable as gross income of the U.S. person with a beneficial interest in the plan and taxed currently, to the extent the amounts meet the requirements of section 83;84 and (2) income accretions in the foreign plan that are distributed or made available for distribution to the U.S. beneficiary are taxable to that person in that same year, to the extent provided for under section 72.85 What is not apparent is that the term "distribution" under section 402(b) does not include transfers and rollovers between foreign plans that are nonexempt plans because they are simply not structurally U.S. trusts to begin with. In fact, transfers from a foreign plan to another foreign plan in the form of rollovers are treated as taxable distributions for U.S. tax reporting purposes absent specific exemptions under this section. One would hardly consider resorting to the provisions of section 402(b) as being in the best interests of the beneficiary because the individual would likely be subject to U.S. tax on contributions made by the foreign employer, or on rollovers or transfers between foreign plans; and income accretions made available to the U.S. taxpayer without actual distribution. A U.S. beneficiary of a foreign plan under section 402(b) should expect to be taxed on almost all components of the foreign plan without any recourse for treating the plan as a foreign grantor trust,86 such that future distributions made from the plan would no longer be subject to additional tax.87

To mitigate the risk of double taxation regarding these foreign plans, a U.S. beneficiary may opt to treat the foreign plan as a foreign grantor trust under reg. section 1.402(b)-1(b)(6). Doing so would exempt future distributions from the plan (including rollovers and transfers between foreign plans) from additional U.S. taxation. However, this provision can only be applied if the beneficiary's employee contributions are "not incidental when compared to employer contributions" and the "applicable requirements of subpart E are satisfied."88 No further guidance is provided under this reg subsection to enlighten U.S. taxpayers and their advisers. From our perspective, taking a position under this obscure subsection of regulatory guidance could be quite the gamble given the overall lack of clarity in how these provisions operate.

A better option in the long run for U.S. beneficiaries of foreign plans is to report the plan itself as a foreign grantor trust. As mentioned, this option only becomes available as an exception to the exception under reg. section 1.402(b)-1(b)(6).89 A deliberate classification of a foreign plan as a foreign grantor trust under subchapter J rather than as an exception to the exception under reg. section 1.402(b)-1(6) would subject all contributions and income accruals to current U.S. taxation but will eliminate U.S. taxation on future distributions. In essence, the foreign plan would be treated as a post tax plan, operating similarly to a U.S. Roth IRA.90 However, unlike U.S.-based Roth plans, the only monetary limits to savings under the foreign plan would be the limits placed on it by the foreign country's laws.

Still, resorting to a Machiavellian fix to mitigate the risk of double taxation of U.S. persons with beneficial interests in foreign plans leaves much to be desired. The end does not justify the means. More work is needed to recalibrate the statutory tax framework used to classify foreign occupational and personal pension plans to narrow the tax gap between the U.S. persons with domestic plans and those with foreign plans. After all, because U.S. persons are taxable on their income worldwide, regardless of how and where it is generated, there seems to be no reason why a U.S. person working in the United States for a U.S. employer should incur no tax on contributions and income accruals in a tax qualified plan while a U.S. person working for a foreign employer overseas91 participating in a mandatory foreign plan is subject to double taxation on the same components.

Super taxing Australian superannuation funds

Based on the above, it is abundantly clear that theoretically all foreign funds coming to the United States with their new U.S. residents are treated equally badly under the existing U.S. tax regime. However, in practice the devil is in the details. For those coming to the United States with funds that closely resemble U.S. domestic retirement plans, the answer seems to be relatively simple. In fact, it is, at least in the case of the Canadian Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP), perhaps the foreign retirement plan that most closely resembles a traditional 401(k). However, for funds and plans that do not resemble U.S. domestic plans, at times the gap feels insurmountable.

To be fair, super funds do not exist nor resemble any entity or structure in the U.S. tax world. This may explain in large part why, since the IRS has not yet issued definitive guidance on this issue, there is not a single U.S. tax perspective on what a super fund is for U.S. tax purposes. On one hand, it is a foreign pension that would not be subject to any tax-deferred treatment like that extended to a U.S. 401(k) or IRA.92 It could also be a foreign grantor trust if it has a U.S. taxpayer contributor and a U.S. individual beneficiary designated to receive tax-free distributions from the super upon satisfaction of statutory conditions (upon reaching age 65 or retirement).93 Either classification leads to some degree of U.S. taxation on contributions, earnings, and distributions received by a U.S. taxpayer. Because a super fund is a foreign asset, it also adds to the complexity of a U.S. taxpayer's international reporting obligations.

The reverse is also true for Australian taxpayers who invest in U.S. assets through their super funds. Foreign entities that are foreign trusts are subject to a different entity classification framework that results in more or less the same outcome. Under reg. section 301.7701-4, a foreign trust is either an ordinary trust or a business trust for U.S. tax purposes. An ordinary trust exists to preserve assets, while a business trust is used to engage in a trade or business. If the latter, it would be treated as either a partnership or corporation based on certain characteristics. In this regard, Australian corporate taxpayers are much better off than Australian individual taxpayers, as illustrated below by AustralianSuper, IFM Investors, and the ill-fated U.S. Masters Residential Property Fund.

AustralianSuper on Wall Street

Take for example, AustralianSuper,94 Australia's largest superannuation fund with AUD 360 billion in assets and 3.4 million members. It was formed in 2006 after the merger of the Australian Retirement Fund, the Superannuation Trust of Australia, and Finsuper, to cater to employees and employers from any industry or profession in Australia (hence, a public offer fund). AustralianSuper is a statutory trust, which is governed by a trust deed, most recently amended by Order of the Supreme Court of South Australia on December 24, 2021. Under Australian superannuation and tax laws, the legal owner of the assets of the fund vest with its corporate trustee entity, which is AustralianSuper Pty Ltd, a proprietary limited company with Australian resident directors.

To meet its growing needs to invest in international markets, AustralianSuper evolved its corporate structure to have subsidiary operating companies in the United Kingdom, the United States, and China, as well as separate legal entities that hold investments. AustralianSuper has had an office in New York since 2021 and has a third of its overall assets invested in the United States.95 The subsidiary company in the United States is AustralianSuper (U.S.) LLC, a Delaware limited liability company that is wholly owned by AustralianSuper Pty Ltd.

The foreign entity classification regulations list just one Australian entity, an Australian public company, as subject to per se corporation treatment for U.S. tax purposes. It would therefore appear, at first blush, that a privately owned Australian company such as an Australian proprietary limited company (AusPty) would have some flexibility to elect its treatment for U.S. tax purposes or be subject to default treatment as a disregarded entity (DE), association, or partnership based on the number of its members. However, because shareholders of an AusPty have limited liability under Australian corporate laws, it would be unlikely that an AusPty with one member would be able to elect DE classification under the U.S. check-the-box regulations. Assuming for the sake of analysis that the AusPty is owned by more than one member and therefore will not be disregarded for U.S. tax purposes and can be either a corporation96 or partnership, it still cannot be assumed that it would be able to elect DE classification because it's a wholly owned Delaware LLC of the AusPty.

Under the entity classification regulations, a single-member LLC will be de facto a disregarded entity unless an election is timely filed to elect corporate classification for U.S. tax purposes. In this regard, it would be very unlikely that the Australian tax advisers would opt to let sleeping dogs lie and simply let the lone U.S. LLC be treated as a disregarded entity to allow passthrough of the U.S. income, losses, deductions, and tax credits to the AusPty entity. The decision to not elect any corporate classification may be fatal to the AustralianSuper parent entity in Australia, because it is well known that AustralianSuper up until this July was heavily overweight in global equities, a substantial amount of which were U.S. stocks.97 This would mean that there would also be a corollary exposure to U.S. income withholding taxes and estate taxes for Australian taxpayers who have parked their savings in AustralianSuper absent an election to treat the AustralianSuper (U.S.) LLC as a domestic C corporation.

IFM Investors — proving that success takes a village

IFM Investors Pty Ltd was established over 30 years ago by a group of pension funds to invest, protect, and grow the long-term retirement savings of Australian workers. It had approximately AUD 230 billion under management as of December 31, 2024. It is currently owned by 16 Australian pension funds98 and one U.K. pension fund99 that are predominantly industry superannuation funds with 745 institutional investors worldwide. They have offices in Melbourne, Sydney, London, Berlin, Zurich, Amsterdam, Milan, Warsaw, New York, Houston, Hong Kong, Seoul, and Tokyo. IFM Investors Pty Ltd100 has been physically present and actively investing in the U.S. market since it opened its New York office in 2007, just five years after it was formed in Melbourne. IFM Investors has since expanded further into the United States through subsidiary LLC entities, managed as a fund of funds101 investing primarily in U.S. private equities and infrastructure projects. Indeed, IFM funds are actively invested in infrastructure assets in more than 30 of the United States, including the Indiana Toll Road, Switch Inc., Swift Current Energy, and Freeport LNG.

As of the date of this article, IFM Investors has the following Delaware LLC entities: IFM Investors (U.S.) LLC,102] a management services company that is paid on a contract fee basis; IFM Investors Advisors (U.S.) LLC,103 an investment management services company; and IFM Investors (Japan) LLC.104

That an Aussie company would use LLC entities as its entity of choice to operate and expand its investments to the United States is no surprise. An LLC is treated as a disregarded entity105 for U.S. tax purposes generally unless a proactive election is made with the IRS to treat the LLC as a corporation. While the IRS has not published data confirming the rate at which Australian-owned LLC entities file entity classification elections, we don't think it is common. This is because corporate dividends are highly taxed in Australia. Making a U.S. entity classification does not make any sense for Australian taxes, especially because once the entity election is made on the U.S. side (causing the LLC to be classified as a corporation for U.S. tax purposes), there is no room for the Aussie investor to report the LLC to the ATO as anything but a corporation for Australian tax purposes, too.106 The downside to this default classification of the LLC is that an Australian investor that is an Australian discretionary trust would be subject to U.S. estate taxes under this type of setup if the trust were treated for U.S. tax purposes as a foreign grantor trust.107 Interestingly however, the IFM structure in the United States defies the common Australian trust108 structure as the parent entity of the LLC.109 The parent entity of the U.S. LLCs is IFM Investors Pty Ltd, a proprietary limited company that is treated for Australian tax purposes as a corporation. For U.S. tax purposes, a proprietary limited can be classified as a corporation or partnership, which would then provide the ultimate shareholders of IFM Pty Ltd with the ability to pass through income, losses, and gains generated from the U.S. LLCs (assuming filing as LLC-partnerships) and pay taxes based on Australia's integrated tax regime.

If IFM Pty Ltd elected to be treated as corporation for U.S. tax purposes (an LLCcorporation), then all distributions from the LLC to IFM Pty Ltd would benefit from the Australia- U.S. tax treaty for U.S. income tax withholding purposes as well as provide U.S. estate tax protection for its individual investors in Australia (if any).

Doomed and defeated: U.S. Masters Residential Property Fund

Perhaps the most infamous of the Australian superannuation fund investments in the United States the past decade is the U.S. Masters Residential Property Fund (URF). The URF was formed in 2011 by Dixon Advisory Group Pty Ltd (DAG-Australia) and Maximilian Sean Walsh, the former deputy chairman of DAG-Australia and a member of its investment committee. Structured as an Australian unit trust, the URF is treated as a hybrid Australian company with passthrough attributes. A unit trust has members that are the beneficiaries of the trust, and a trustee that has management of the trust assets. Similar to corporate shareholders, the unit holders of a unit trust have limited liability under Australian law because there is no personal liability for the debt or claims against the unit trust by reason of being a unit holder. However, unlike shareholders of a corporation that have interests only in the shares of a company, unit holders have interests in the underlying assets of a unit trust. Under the U.S. check-the-box regulations, a unit trust with more than one member would most likely be treated as a foreign eligibility entity that is an association if it has more than one member, or a disregarded entity if it has a singular member.

DAG-Australia, known as "Australia's most high-profile promoter of self-managed super funds,"110 was a Canberra-based asset management and financial advisory firm that merged in 2017 with Evans & Partners,111 a high end stock brokerage firm based in Melbourne. The merger produced Evans Dixon,112 an AUD 18 billion113 financial services firm that listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) in May 2018114 as a public company.115 It was the fourth largest SMSF provider in the country.116 Both Alan Dixon and his father, Daryl Dixon, were on its investment committee. It was reported by the Australian news media that the investment committee recommended its 4,700 SMSF clients to invest in the URF, the biggest in-house Dixon investment,117 listed as a closed-end fund on the ASX in 2012. At that time, a high Australian dollar made investing in U.S. assets attractive, with the U.S. dollar and U.S. property market weak.118 The URF managed over 600 homes in New York and New Jersey,119 which consisted of distressed U.S. residential properties from the boroughs.120 It was reported that the URF "loaded up on debt to amass a billion-dollar portfolio of New York and New Jersey real estate, charging hundreds of along the way."121 By the time the U.S. lawsuits were filed, the URF had fallen 90 percent in value over five years,122 bringing down along with it the superannuation investments of middle-income Australians with a reasonable amount of wealth accumulated over decades in white-collar professions.123

The URF invested SMSF funds directly in distressed real estate, which was then managed by the Australian fund through its wholly owned subsidiary, Dixon Advisory Group U.S., an urban single-family-home rental business based in New York City and New Jersey. Alan Dixon was the managing director and CEO of Dixon Advisory Group U.S. He was also a shareholder, managing director, and CEO124 of its Australian parent company, Dixon Advisory Group Pty Ltd.125 The public fallout from the URF investments is well-documented and written about in Australia. In April 2024 a class-action settlement was approved by the Federal Court of Australia against Dixon Advisory and Superannuation Services Pty Ltd for approximately AUD 16 million.126 As of the date of this article, the URF is trading on the ASX for AUD 32 cents. Evans & Partners was delisted in November 2024.

A silver lining, really?

The irony of the above is that the Australian investors in the URF really did dodge the U.S. tax bullet because of the unfortunate series of catastrophic events that occurred in 2018. If the URF investments in U.S. real estate were to have appreciated in value, each SMSF member who invested in the URF using their SMSF money would have been subject to adverse U.S. tax consequences because each SMSF investor, as a unit holder to the URF unit trust, has a direct interest in the underlying U.S. real estate owned by the URF. Indeed, one should carefully consider whether acquiring U.S.-based assets through SMSFs would expose Aussie members of the SMSF to U.S. estate taxes because U.S. real estate is a U.S.-situs asset for U.S. estate tax purposes.127

SMSFs are unique in Australia's superannuation system and differ from other funds, because members of these funds are also the trustees, and therefore, are in control and have sole responsibility for their retirement savings and, therefore, all investment decisions. At the same time, trustees must abide by all regulatory requirements and responsibilities. For example, they must do all the paperwork to set up an SMSF or engage a professional accountant to do so, and then engage more professionals to undertake a valuation of its assets, prepare and file reports with the ATO and conduct annual auditing. SMSFs are not cheap, but they are a popular method for holding business assets and investments.

An SMSF from a U.S. perspective is essentially a revocable trust, given that its members (the beneficiaries) are also trustees. For U.S. tax purposes, an SMSF could be treated as a foreign grantor trust if there is a U.S. person who contributes and a U.S. person who benefits from the trust. Some SMSFs fall squarely within these parameters when a U.S. citizen residing in Australia makes voluntary concessional and nonconcessional contributions to the fund, and another U.S. person (or the same one) is entitled to receive retirement distributions from the same fund. Treatment as a foreign grantor trust means that all the income, gains, deductions, and credits accrued in the SMSF are immediately attributed to the U.S. person who made contributions to the fund. However, the U.S. person would also be able to claim FTCs for Australian taxes paid by the SMSF on its Australian tax returns. Theoretically, because contributions and earnings accrued in the SMSF would have already been subject to U.S. tax, any distributions received from the fund would constitute posttax money and be tax free. While the foregoing addresses U.S. income tax treatment of an SMSF as a foreign grantor trust, the same also applies in the U.S. estate tax context.128]

It is certainly not uncommon for Australian members of an SMSF to acquire U.S.-situs rental real estate using SMSF money, such as those acquired through the URF. Perhaps if the URF had held each U.S. real estate investment through domestic single-member U.S. LLCs formed in the same state as the real estate to provide additional liability protection to the URF,129 one could then take the position that an SMSF that owns a U.S. vacation home that is occasionally rented out to third parties remains a foreign trust, while an SMSF that owns commercial properties for lease certainly would be geared toward a business entity classification such as a partnership or corporation rather than a foreign trust. To date, while the IRS has not reached any definitive guidance on the U.S. tax classification of SMSFs for U.S. tax purposes, through its escalating enforcement and compliance actions130 targeting U.S. persons who have either inadvertently failed to disclose SMSF ownership or pay tax on income accrued or withdrawals taken from their SMSFs, those U.S. persons have been subjected to egregious penalties under section 6677 for failure to file forms 3520/3520-A.131

The IRS and superannuation: on a collision course with history

Like the U.S. government, the IRS has a tendency to bury its head in the sand and rely on the momentum set in place by its aggressive international enforcement actions against international institutional players and high-networth families.132 But you can't bring a knife to a gunfight. Since the 2010s, the IRS has done exactly that where foreign pensions are concerned.

The June 2015 private letter rulings

Foreign trusts, like the AustralianSuper fund, continue to evade definitive U.S. tax classification and treatment.133 Indeed, it has been 10 years and 45 days since the IRS published three private letter rulings classifying an Australian superannuation fund as a foreign trust for U.S. tax purposes and providing its first comments on the issue. In its 2015 advice to U.S. taxpayers in LTR 201538008, LTR 201538007, and LTR 201538006, the IRS held that a foreign trust providing superannuation-type benefits to its members constituted a trust for U.S. federal income tax purposes and should be reported accordingly. While it has never been officially confirmed that the trusts in question were SMSFs, it has been informally acknowledged in international tax circles in Washington and elsewhere that they were.

The letter rulings have been in the proverbial legal ether for almost a decade, and the implications raised by the classification of SMSFs as foreign trusts continue unabated. The most consequential of these concern whether SMSFs, as foreign trusts created under Australian superannuation laws to provide retirement savings for an employee in the Australian workforce, should then be further classified as employee trusts subject to section 402(b) treatment at all. Unfortunately, the IRS's position (as first outlined in the letter rulings) does not address this question. Rather, it seems to begin with an assumption that an SMSF is a foreign employee trust, without stopping to consider if this is in fact the appropriate category for a private pension fund that is an integral part of Australia's superannuation regime. Indeed, the IRS has refused to issue any further administrative guidance to clarify whether an SMSF is a foreign trust or in fact a foreign employee or pension trust. This has led to the widespread practice of reporting SMSFs as employee trusts that are foreign grantor trusts under section 402(b) for U.S. tax purposes, all of which has helped to shape the dialogue moving forward.

Rev. Proc. 2020-17

In 2018, the IRS instituted a robust foreign trust reporting enforcement campaign that aimed to improve forms 3520 and 3520-A compliance.134 The intent was to:

- improve U.S. taxpayers' and practitioners' knowledge of a U.S. person's requirement to report ownership of, and transactions with, foreign trusts;

- decrease the percentage of late filed and incomplete forms 3520/3520-A; and as a corollary,

- increase the number of properly filed forms 3520/3520-A.135

Section 6048 provides the statutory mandate for foreign trust reporting implemented by Form 3520, "Annual Return to Report Transactions with Foreign Trusts and Receipt of Certain Foreign Gifts," and Form 3520-A, "Annual Information Return of Foreign Trust with a U.S. Owner." While section 6048 provides an exception from reporting for certain transfers to foreign compensatory trusts under section 402(b), which are reported as compensation income by the U.S. person on an applicable U.S. federal income tax return, the lack of any specific list identifying which foreign trusts are in fact foreign compensatory trusts under section 402(b) makes this exception an elusive one. Indeed, most foreign plans that are foreign trusts would generally fall within the parameters of section 6048, which would impose annual obligations on U.S. beneficiaries to file Form 3520, and if the foreign plan is treated as a foreign grantor trust for U.S. tax purposes, Form 3520-A.

In the absence of specific guidance on many foreign plans, tax practitioners have defaulted to reporting those in which a U.S. person has a beneficial interest (either directly or beneficially) as foreign trusts subject to U.S. foreign trust reporting requirements, or worse, as passive foreign investment companies subject to Form 8821 and disclosure via a foreign bank account report and the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act. There is, however, no consistency among tax practitioners in reporting foreign plans as foreign trusts subject to Form 3520 or Form 3520-A filings. Out of an abundance of caution, and in the absence of IRS guidance directly on this issue, many international tax practitioners defaulted to characterizing foreign plans as trusts reportable on either Form 3520 or Form 3520-A. However, doing so provided too broad a net, because it caught foreign pension-like plans that present low risk of facilitating tax evasion because of the strict regulatory overview by their respective government agencies and the relatively low statutory lifetime contribution limitation thresholds that were often included in the legislation creating these plans.

In March 2020 the IRS issued Rev. Proc. 2020- 17, 2020-12 IRB 539, to provide a foreign trust reporting exemption for certain tax-favored foreign retirement and nonretirement savings plans that meet specific criteria. It also provided an exemption for rollovers from one foreign plan to another if both plans meet the requirements of Rev. Proc. 2020-17.136 It appears that the IRS recognized that the administrative burden of reviewing every single Form 3520 or Form 3520-A filed to disclose interests of U.S. persons in foreign trusts could not be justified, particularly because the existence of these foreign trusts were likely already subject to annual tax reporting under section 6038D as specified foreign financial assets.137]

While Rev. Proc. 2020-17 has provided some degree of relief to foreign plans not exempted from U.S. taxation under previous IRS guidance,138 such as Canadian Registered Education Savings Plans and Canadian Registered Disability Savings Plans, it does not go far enough to cover other foreign plans that should receive the same exemption. The very narrow parameters for determining tax-favored retirement plans or tax favored nonretirement savings plans in Rev. Proc. 2020-17 left out foreign plans that need IRS guidance, such as Australian superannuation funds and Canadian tax-free savings accounts. Indeed, the parameters are so narrow that perhaps only the Canadian savings plans mentioned above would even qualify for the foreign trust reporting exemption under Rev. Proc. 2020-17. In addition to providing narrow parameters for exempting foreign plans from foreign trust reporting, Rev. Proc 2020-17 did not provide a solution to alleviate U.S. income taxation of income accruals and employer contributions in these plans. While the procedure did eliminate the annual tax reporting requirement for qualifying foreign trusts that are foreign plans, and as a corollary, avoid substantial penalties for noncompliance, it did not go far enough to provide effective relief for foreign plans in countries that are either not legally structured as trusts domestically,139 or do not tolerate low contribution thresholds for savings as in the United States. In light of this, many U.S. international tax practitioners who deal regularly with Australian super funds, some of whom are IRS attorneys, agree that Rev. Proc. 2020-17 cannot be applied to exempt Australian superannuation funds from foreign trust reporting. We would strongly recommend taking these individuals' word for it over Google's AI summary of the current state of Aussie super funds.140

Section 897 to the rescue?

The plight of the Australian super fund could have once again caught the attention of the international tax community on June 7, 2019, when the U.S. Treasury introduced temporary regulations under section 897(l), related to the availability of an exemption from the application of the 1980 Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act[141] on the disposition of U.S. real property interests (USRPIs). Under section 897(l), entities qualifying as qualified foreign pension funds (QFPFs)142 and qualified controlled entities (QCEs) are exempted from FIRPTA withholding on the disposition of their interests in USRPIs (which include interests in mines, wells, and natural deposits and interests in U.S. domestic corporations, unless the taxpayer can demonstrate that the corporation was not a United States real property holding corporation at any time in the five years before the disposition).143

Indeed, qualifying for the section 897(l) exemption can provide significant relief to foreign pension funds holding USRPIs. In contrast to the general rule in section 897(a)(1), nonresident alien individuals holding interests in QFPFs are not taxed as if they were engaged in a U.S. trade or business and the resulting gain or loss was effectively connected with such trade or business in the United States when the QFPF disposes of USRPI investments.144 Even more importantly, qualification as a QFPF or QCE exempts the entity from the 15 percent FIRPTA withholding requirement that would otherwise apply to the transfer. Because the withholding requirement is applied on the fair market value of the USRPI, this can leave a foreign investor in quite a bind, especially if the investing entity does not have sufficient liquidity in its other assets to satisfy its withholding obligations.

On that basis, it was of significant interest to the international tax community that this exemption be as broadly applicable as possible, to ensure that the greatest number of foreign pensions and funds are qualified. Comments were requested by the IRS in 2019 and several Australian entities provided comments, including PwC Australia and the ASFA.145 Of chief concern to these groups was the narrow definition applied to QFPFs and QCEs, because the commentators believed there was a significant risk that super funds, in particular, because of the expanding role they have taken in Australian financial planning and investment, would not qualify. Similarly, they raised concerns about the application of the bright-line rules regarding the requirement that at least 85 percent of the value of the benefits expected to be paid out of a fund were to be retirement and pension benefits, and 100 percent must be "qualified."146 Unfortunately, when the final regulations became effective on December 29, 2022,147 the IRS once again failed to fully assuage these concerns, taking the view that avoiding abuse of this exception necessitated the narrow scope for these definitions, adding a potential hurdle for super fund interest holders to overcome when filing tax returns in the United States.

Foreign trust regulations

On May 8, 2024, the U.S. Treasury issued proposed foreign trust regulations148 that included an expansion of the exception for tax-favored foreign retirement trusts initially introduced under Rev. Proc. 2020-17. However, the proposed regulations provide no relief for the current problems related to foreign pension and retirement plans that do not qualify as pensions or pension funds under different iterations of the U.S. model tax treaty, because none of them are structured as domestic trusts. Indeed, the issues associated with contributions, accrued earnings, and distributions to and from such foreign retirement plans, including rollovers between plans, remain not just unaddressed but exacerbated by the proposed regulations. As had become somewhat customary, the international tax community again reached out to the U.S. Treasury with comments and concerns about the proposed regulations. Chief among these was the imposition of significant penalties on non-willful taxpayers for failing to report transactions that may not be thought of as otherwise reportable — things like nontaxable rollover transactions, beneficial transfers on death, and other deemed dispositions resulting in constructive receipt of trust assets by U.S. taxpayers. Compounding this issue, as the correct U.S. tax classification of many of these investments is still at best ambiguous, owners of many foreign retirement plans may be penalized for failing to report transactions with entities that they're not even sure are actually foreign trusts.

As pointed out by the American College of Trust and Estate Counsel (ACTEC) in its comments,149 a significant number of Americans live and work abroad and contribute to foreign pension plans. In many cases, this is because of sheer necessity, because U.S.-based plans often have restrictions on contributions and distributions for nonresident U.S. citizens, and many foreign plans, including super funds, mandate employer contributions.150 However, participation in these plans also carries a significant risk to U.S. taxpayers, who are left trying to decipher and comply with the maze of international tax filing requirements imposed on foreign investments. Because U.S. tax practitioners cannot even agree on how to classify these plans that do not qualify as pensions or pension funds, large penalties for failure to properly report the assets may result. Initially, there was optimism that Rev. Proc. 2020-17 had resolved many of these issues, especially in light of its more expansive use of the term "foreign trust" to include trusts, funds, accounts, and other arrangements providing pension, educational, and disability benefits. But the excitement was short-lived as it became apparent that many foreign pension arrangements were still unlikely to qualify.

Hoping to finally obtain some clarity on some issues, ACTEC made a series of recommendations, including the introduction of a regime akin to the check-the-box election regime for business entities that allows eligible foreign funds to elect treatment as foreign trusts for U.S. tax purposes. This would allow entities formed in civil law countries that do not recognize trusts to elect classification as trusts for U.S. tax purposes, giving taxpayers with these investments clarity on the exact tax treatment and filing requirements. However, these proposed regulations have not been finalized, so it remains to be seen what, if anything, will be included.

The U.S. tax treaty stalemate

The U.S. legislative stalemate on bilateral tax treaties is preventing a much-needed fix to article 18 of the U.S. model tax treaty. As the foregoing section on IRS administrative action has illustrated, the narrow parameters administratively set by the IRS to classify and tax foreign pension funds has resulted in a patchwork of tax laws and administrative practice that has not been helpful to the plight of the Australian super fund. It has been intentionally excluded from these remedial measures. The reason for this special treatment eludes us.

Further, Congress has not been particularly receptive to providing a legislative fix to the U.S. tax classification and treatment of Australian super funds. This is why the United States remains in the proverbial weeds and behind the rest of world when it comes to acknowledging that many countries have reformed their pensions in a manner that is absolutely inconsistent with the U.S. existing pension and retirement scheme. The United States has remained staunchly dependent on an antiquated Social Security regime that is based on public contributions (payroll taxes) into government trusts that are then invested by the government into who knows what, in the hope that someday, when it is our turn to retire, we will receive a check every month to help tide us over until death comes knocking at the door.

The rest of the world took a more proactive approach, of course. Over the past decade, countries around the world have reformed their pension regimes to address the challenges of an aging population with increasing longevity and low fertility by encouraging fully funded private pensions in the workplace and personally directed by individuals. It has, thus far, paid off. The OECD documented in its 2022 report that private pension plan assets have surpassed public pension assets by trillions of dollars.151 Of these private pensions, the DC plan arrangement is preferred to the more traditional DB plan. In Australia DB plans have been phased out except for possibly judges and politicians because companies are unable to fund the future liabilities. However, the tradeoff appears to be that individuals with DC or hybrid plan arrangements have more access to their individual accounts because they are at least partially responsible for managing their retirement investments.152 These accounts are also subject to preferential tax treatment in their home countries so that savings are accumulated as long as possible, and, in some cases, distributions upon retirement age are not taxed at all.153 Such is the nature of the bargain struck between public and private stakeholders to provide adequate retirement income for everyone without increasing taxes.

In other countries, retirement savings are accumulated in vehicles other than traditional pension funds.154 These include employers' books, pension insurance funds, and other privately managed vehicles.155 For example, the Korean pension system relies on services provided by entities in the financial services industry — such as banks, mutual funds, and insurance companies — to provide voluntary occupational and personal pension contracts with individuals. In most OECD countries that follow the Chilean system, mandatory individual accounts are managed by specialized fund and management companies (pension entities) that own IRAs. The pension entities are legally separate from the financial group to which they belong.156 In Australia157 and the Netherlands, the superannuation funds and pension funds are operated by independent stand-alone entities that are not owned by providers of other financial services. Even in countries in which pensions are provided by public entities or institutions, such as Lithuania and the United Kingdom, the pension providers are not trusts but not-for-profit public corporations.158

More importantly, the legal structure for private pension providers around the world varies. Providers structured as pension funds are independent entities with legal personality and capacity and have their own governing boards, such as in Australia, Denmark, Finland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Germany's pensionkassen. Others are contractual arrangements between the individual and the pension entity with a segregated pool of assets without legal personality or capacity such as in Chile, the Czech Republic, Mexico,159 Portugal, and Turkey. Only a few countries, like the United States, have pension funds in trust structures in which the trustee legally owns the pension fund assets and administers the assets in the interests of the plan participants who are beneficiaries of the investments.

What this all boils down to is the reality that retirement savings in foreign plans outside the United States are not limited to trust structures with traditional trustees and beneficiaries. Because of pension reforms in the past decade, the legal structures in which pension funds are held, invested, and from which they are distributed, are not likely to meet the requirements of a taxqualified retirement plan for U.S. tax classification purposes under section 402(b)(2) and (b)(4) to qualify the U.S. taxpayer participating in these plans for tax deferral on employer contributions, investment earnings, and distributions.160 Moreover, because most OECD countries now have in place mandatory occupational pension plans,161 U.S. taxpayers who are employed abroad cannot opt out of their employer-funded private pension plans, which give them more access and control over their accounts.162 This in turn means that U.S. taxpayers will be currently taxable on employer contributions and income accumulated and undistributed in their respective accounts that, if held through a trust established in the foreign country of employment, such as Australian SMSFs, would likely be classified, and immediately taxable, in the United States, as foreign grantor trusts.

U.S. persons in countries that use nontrust vehicles as pension fund providers, such as private corporations, are not spared adverse U.S. tax treatment because of their beneficial interests in these vehicles. For example, in Mexico, individual accounts held by a Mexican private corporation, referred to as Administradoras de Fondos para el Retiro (Afores), are invested in the stock of a legal financial entity managing investment portfolios, known as a sociedad del inversion especializada en fondos para el retiro (Siefore).163 The interest held by the individual is an ownership in interest in the Siefore, which manages three compulsory portfolios comprising government bonds, domestic securities, and foreign equities. Both the Siefore and its portfolios would likely be taxable in the United States as a PFIC, subject to the PFIC tax and international reporting requirements with hefty penalties for noncompliance.164 There is no income tax treaty relief available to U.S. taxpayers with beneficial interests in an Australian superannuation fund or Mexican retirement fund to avoid double taxation of contributions and earnings in these retirement vehicles.165 To make things worse, both types of private pension plans would also be subject to burdensome U.S. international tax reporting on an annual basis because neither would be classified as a tax-favored foreign retirement plan or nonretirement savings plan under Rev. Proc. 2020-17. Truly, there is much work left for the IRS and Treasury to remedy this disparate outcome for U.S. beneficiaries of foreign plans.

Because most pension reforms in OECD countries were implemented after their bilateral tax treaties with the United States entered into force, it is not surprising that the pension articles in these treaties do not reflect structural and legal changes implemented by the reforms. However, a solution can still be found within the existing pension articles if the IRS or Treasury were to explore the position that these private pension plans are hybrid social security vehicles implemented by foreign governments under their social security programs to support individuals and their dependents in maintaining a certain level of income because of old age, disability, death, sickness, work injury, or unemployment and the like. Social security programs provide cash benefits or benefits in kind to individuals in part through employment, because contributions made by employers, employees, or both, largely fund the programs. In short, retirement savings contributed to and accumulating within foreign private pension plans constitute foreign social security in OECD countries that have undergone pension reform and therefore should not be subject to tax by the United States under the applicable bilateral tax treaty provisions.

At this point, it would be useful to point out that both the tax treaty and the totalization agreement166 are types of international agreements the United States uses to coordinate various aspects of the Social Security program.167 Although similar in function to tax treaties, totalization agreements are legally classified as congressional-executive agreements concluded under statute.168 Coordination of the social security programs between two countries is addressed either exclusively through an executive agreement or in a treaty, or simultaneously in both. This bifurcated approach has resulted in overlapping and potentially dueling agreements that give rise to interpretational issues and create uncertainty for workers and administrators.169

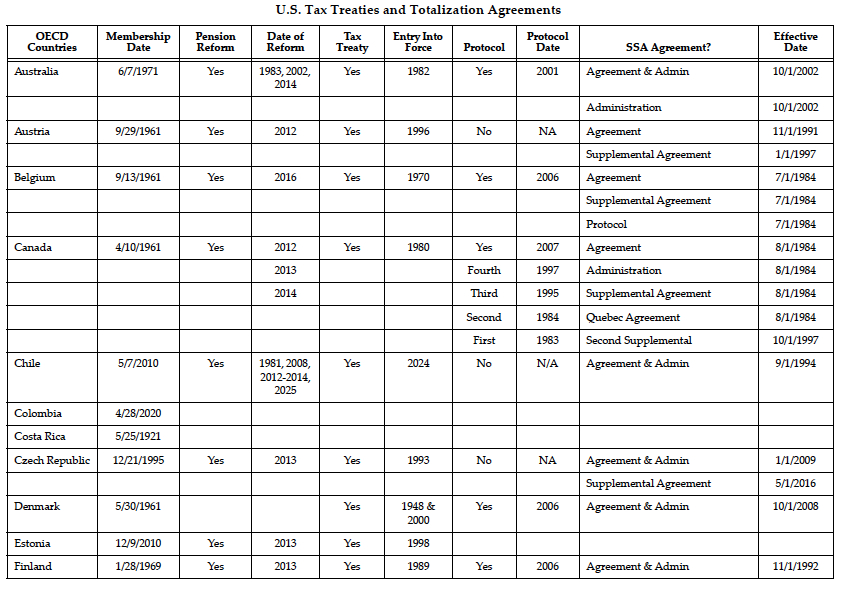

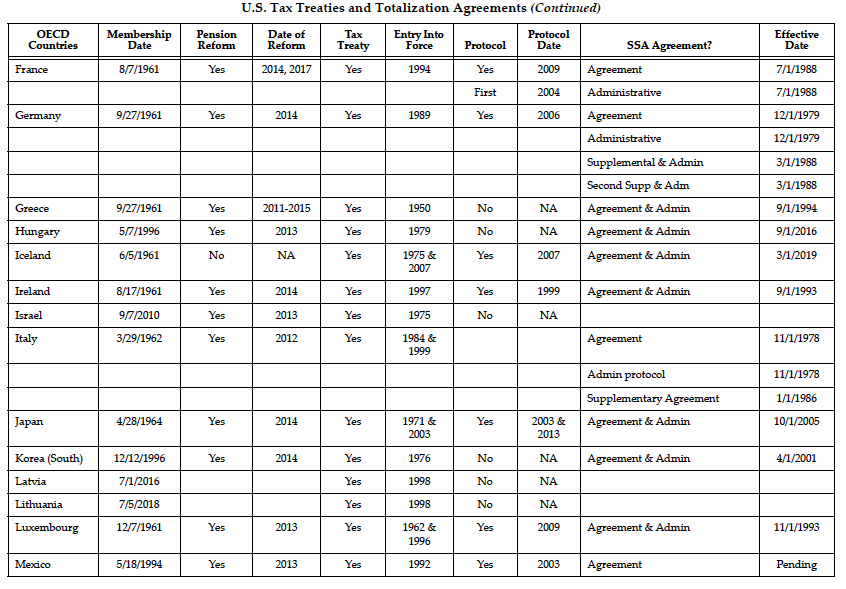

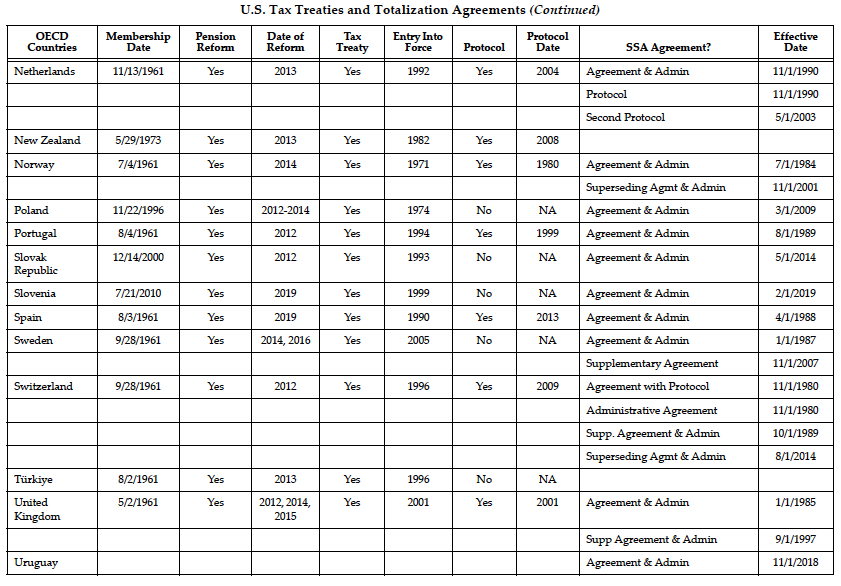

This appears to be the case with U.S. international agreements with OECD countries. Our review of totalization agreements between the United States and OECD countries, as illustrated in the following table, shows that while only a few of the agreements were ratified by Congress after the bilateral tax treaties entered into force, these few acknowledge that the pension reform in the respective countries have created hybrid social security vehicles. The Australia-U.S. totalization agreement explicitly references the employer contribution portion of an individual's superannuation fund as substantially equivalent to social security for U.S. purposes.170 Similar provisions exist in the U.S.- Slovenia totalization agreement, which includes an explicit reference to the "compulsory participation in social insurance" system.171 This of course gives rise to the possibility that, if the U.S. totalization agreements were updated, many more of the these foreign private pension plans would likely have components that would also be recognized as constituting or equivalent to U.S. Social Security. This acknowledgment in bilateral totalization agreements that foreign private pension plans would be in lieu of, similar to, or equivalent to U.S. Social Security should be recognized as a definitive classification for tax treaty purposes.

The table also shows that the U.S. bilateral tax treaties with the other 37 OECD countries were entered into force before pension reforms were implemented in 28 of them. Of these 28 countries that have undergone pension reform, eight (the Czech Republic, Greece, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Korea, Sweden, and Turkey) have never entered into protocols with the United States to update their existing tax treaty provisions. Therefore, relying on the pension articles in the respective bilateral tax treaties in force to remedy the unfortunate and inevitable double taxation of foreign pension plans in these 28 countries under U.S. domestic tax laws should not be the last resort for resolving a case of double taxation of a U.S. person's crossborder pension.172 Rather, we recommend a corresponding review of the applicable bilateral totalization agreement be undertaken to confirm if the cross-border pension at issue is part of the foreign country's social security program after pension reform. If such is the case, then relief may be available under the applicable tax treaty provision to all or a portion of the pension.

A 'happy ever after' for Australian superannuation?

This brings us back to the conundrum of what we are supposed to do with Australia's massive super fund war chest, which appears to be once more back on track with plans to invest heavily in U.S. and international markets. Based on a recently issued report endorsed by the Super Members Council, Australian pension funds are forecast to have US $2.6 trillion invested globally by 2035, including US $1 trillion in the United States and specifically US $140 billion in U.S. private markets, primarily in infrastructure and private equity.173 With such staggering forecasts, the separate pledges made by Australian superannuation funds, IFM Investors, and Aware Super to the U.K. government totaling US $29 billion over a five-year period pales in comparison.174 Could it be that the only way forward for Australian super fund investments in the United States is through a corporate structure representing pooled funds from Australian super fund entities, rather than through Aussie individuals investing directly through their own super funds such as SMSFs? It certainly appears that investments made by IFM Investors Pty Ltd and AustralianSuper are not at all subject to adverse U.S. tax treatment because the U.S.-facing legal structure of these funds (LLCs) under the check-the-box regulations would be a corporation.

On the other hand, individual Aussies who invest in the United States through their own super fund accounts (SMSFs, industry funds, or employer funds) do not possess the gravitas that the Australian super fund giants possess. Unless one has a cross-border tax lawyer on the team, the everyday Aussie investor is not informed enough about U.S. entity tax classification technicalities to either: (1) file an election to treat their super fund investing directly in the United States as a corporation; or (2) file an election to treat the wholly owned LLC of their super fund as a corporation to avoid default classification as a disregarded entity. Absent knowledge of the foregoing, the everyday Aussie person who invests in the United States, and even a U.S. person in Australia (or back from Australia) who owns a super account, must bear the brunt of U.S. taxation because the IRS treats these funds as foreign trusts, with individual Aussie members exposed to: (1) U.S. income taxation on accrued investment income and gains in the super both during the accumulation phase and on pension withdrawals on retirement; and (2) U.S. estate taxes on the underlying U.S.-situs assets, rather than as foreign retirement and pension funds equivalent to U.S. IRAs under article 18 of the Australia-U.S. tax treaty.175