- within Energy and Natural Resources topic(s)

- with readers working within the Business & Consumer Services and Property industries

- within Real Estate and Construction topic(s)

Floating LNG (FLNG) facilities and FSRUs have emerged as transformative components of the global LNG value chain. FLNG facilities, used to liquefy natural gas, offer an opportunity for emerging markets to commercialise gas reserves when onshore liquefaction infrastructure may not be suitable and there are no means to export gas via pipeline. FSRUs, used for importing LNG, are particularly attractive in emerging markets where surging energy demand often coincides with underdeveloped infrastructure, limited financing options, and uncertain regulatory environments. With lower upfront capital requirements, shorter construction lead times, and enhanced deployment flexibility compared with conventional onshore facilities, these floating technologies offer a means to accelerate market participation.

Recent developments in global LNG markets signal a period of transition for liquefaction and regasification technologies. The rapid commissioning of new LNG supply projects in several markets – North America, in particular – combined with anticipated moderation in demand growth across major importing economies may result in a temporary phase of oversupply, although this may be mitigated (or even outweighed) by rising electricity demands, led by power-hungry data centres and artificial intelligence (AI). This landscape creates conditions conducive to innovation and strategic deployment of both FLNG and FSRUs.

Global LNG supply and demand trends

Expansion of liquefaction capacity

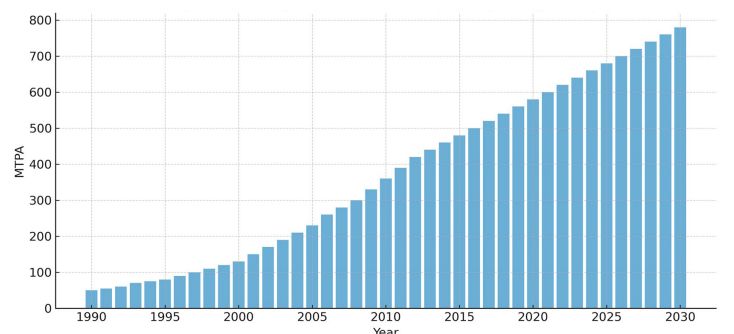

Global LNG supply has expanded significantly over the past decade. In 2015, total liquefaction capacity stood near 300 million tpy; by 2024, it exceeded 490 million tpy. Projections to 2030 suggest a potential capacity of approximately 740 million tpy, assuming full realisation of announced projects. Figure 1 illustrates this upward trajectory.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), more than 200 million tpy of new capacity may enter the market between 2025 – 2030. This expansion has led to heightened discussion about the risk of medium-term oversupply of LNG, particularly if demand in Asia and Europe fails to grow at anticipated rates. Some estimates suggest that by 2030 the market could face a structural surplus of 50 – 70 million tpy, equivalent to around 10% of global demand.

Changing demand patterns

However, it is possible that the anticipated LNG oversupply will be partially or even wholly mitigated by upward demand pressures, especially due to LNG's role as a transition fuel. Until electricity storage, hydrogen, and renewables scale sufficiently, natural gas will continue to play a transitional energy role, filling the intermittency gaps of renewable technologies. In addition, the rapid expansion of AI is anticipated to significantly increase demand for power from data centres, with the IEA forecasting that demand will double by 2030. Separately, LNG is also increasingly being used as a bunker fuel in response to tightening regulations on marine emissions.

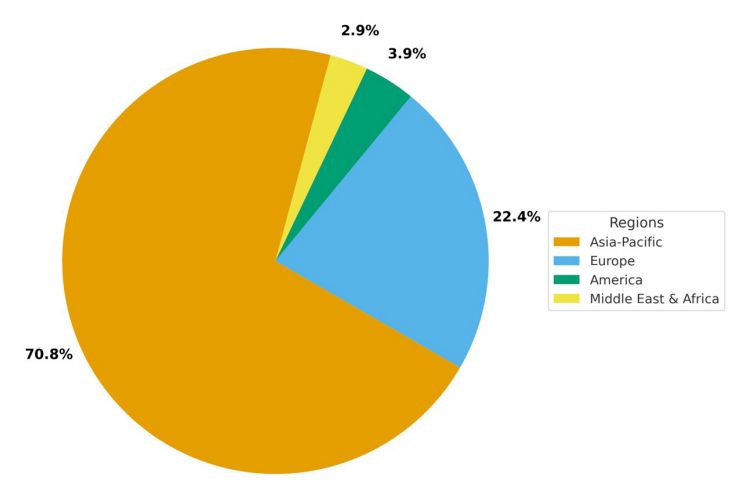

Demand growth remains concentrated in Asia, which accounts for roughly two-thirds of global LNG imports. In 2024, the Asia-Pacific region consumed approximately 270 million tpy, followed by Europe at 100 million tpy, and the Middle East and North Africa region at 50 million tpy (Figure 2). However, demand growth has slowed in major Asian importers such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and China. China saw an 18% decline in LNG imports in early 2025 relative to the previous year due to a range of factors, including increased domestic production, higher spot prices, and weakened industrial sector performance. India and parts of Southeast Asia have also reported lower gas demand.

The European market, following its rapid expansion in response to pipeline disruptions after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, is expected to plateau as energy efficiency and renewable deployment accelerate. Collectively, these trends contribute to a more uncertain demand outlook.

What does this mean for floating infrastructure?

Evolution of FLNG

FLNG technology has moved from experimental to commercial maturity. Early projects such as Prelude (Shell in Australia) and PFLNG Satu (Petronas in Malaysia) faced cost overruns and operational delays, but have since achieved stable output levels. Current global FLNG capacity stands near 14 million tpy, with expectations to surpass 40 million tpy by 2030.

FLNG has developed as a response to both economic and strategic drivers. FLNG offers a means to exploit 'stranded' gas

Figure 1. Global LNG liquefaction capacity, including existing, final investment decision (FID), and pre-FID, 2015 – 2030. Based on analysis by Rystad Energy and published in the International Gas Union's (IGU) World LNG Report 2025.

Figure 2. Regional LNG demand share for 2024. Based on analysis by Rystad Energy and published in the IGU's World LNG Report 2025

fields that are unsuitable or uneconomic to develop using traditional onshore infrastructure, or where there is no domestic market for gas or ability to export via pipeline to other markets. Strategically, it provides host countries with greater flexibility and sovereignty over offshore resources, while reducing land-based environmental and social impacts. The modularisation and standardisation of FLNG designs, and the innovative new 'fast' LNG designs offered by some providers, are also reducing costs and shortening construction timelines, allowing smaller operators and national oil companies to consider FLNG as a viable development pathway. FLNG can also be deployed in a similar manner to traditional onshore liquefaction infrastructure by allowing for incremental development.

Recent market dynamics have further strengthened the rationale for FLNG investment. The surge in LNG demand following Europe's diversification away from Russian pipeline gas, coupled with the broader global shift towards gas as a transitional fuel, has underscored the value of flexible and scalable liquefaction capacity. Moreover, FLNG's offshore location can enhance energy security by avoiding geopolitical and permitting challenges that sometimes delay onshore projects, as well as the security issues that can hinder the development of onshore liquefaction infrastructure in emerging markets.

FLNG is not without its challenges. Technical complexity, high capital intensity, greater exposure to climactic conditions, and limited operational track records have constrained large scale adoption to date. Yet, as technology matures, FLNG is increasingly viewed as a critical enabler of gas development, particularly in developing regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America, where it can unlock resources and support the transition to a more flexible, lower-carbon global energy system.

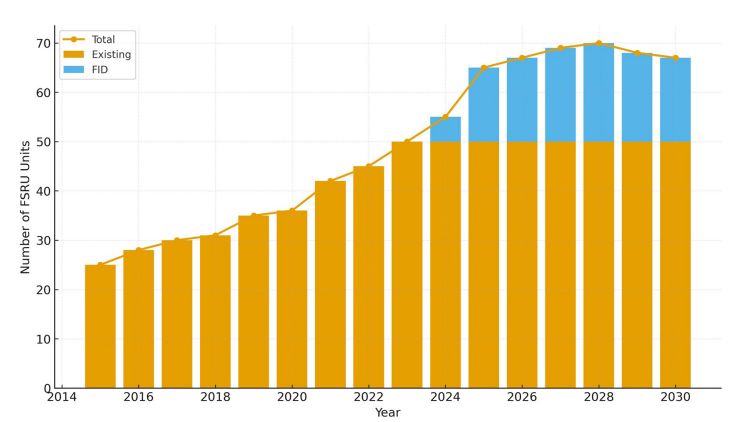

Growth of FSRUs

FSRUs facilitate the import of LNG without the need for extensive onshore infrastructure. In 2015, only around 20 FSRUs were operational globally; by 2025, the fleet was estimated to exceed 50 active vessels, with projections of around 65 by 2030 (Figure 3). The majority of these units serve emerging markets in Asia, Latin America, and Europe's periphery. As of 2023, global FSRU capacity was about 186 million tpy, representing roughly 16% of total regasification capacity.

The attractiveness of FSRUs lies in their relatively low capital intensity, mobility, and speed of deployment. Leasing arrangements also make FSRUs a practical solution for jurisdictions with volatile demand or uncertain long-term policy direction, or simply without the means of accessing pipeline gas. Consequently, they are ideal in emerging markets, and are deployed in countries as diverse as Bangladesh, Vietnam, Egypt, and Germany.

Deployment of FSRUs does involve a trade-off, however. Because the size and output of FSRUs are limited compared to large onshore terminals, FSRUs may not be sufficient to meet very large or baseload demand alone. They may, however, offer a useful solution in supporting the increasing role of gas peaker plants that support the power grid. Whilst the CAPEX involved with FSRUs is considerably lower than onshore equivalents, operational costs (charter fees, maintenance, maritime safety, and crew) can be higher than for fixed onshore terminals over time.

Implications of changing demand

In an oversupplied market, new FLNG investments into emerging markets are potentially at risk. Potential users of FLNG as a solution to commercialise gas reserves may be more exposed to a fall in LNG prices that may result from this oversupply given the potentially marginal nature of such reserves. However, innovative project structures may be able to accommodate a lower price environment, partly due to increased competition among FLNG producers. Projects targeting niche or regional markets may also benefit from liquefaction tariff price points that are supported by a blend of longer-term offtake contracts and spot contracts.

An oversupply in the market can also confer distinct advantages to FSRU-based importers. FSRU-equipped nations can capitalise on lower LNG prices by entering shorter term contracts, reducing exposure to long-term price risk. For example, in 2024 – 2025, several South and Southeast Asian importers, including Bangladesh and the Philippines, renegotiated supply contracts at favourable terms.

Furthermore, FSRUs provide scalability that matches the uncertainty of emerging-market demand growth. Countries can lease units for defined periods, relocate them as demand evolves, or transition to onshore terminals once consumption stabilises. This flexibility is particularly valuable in volatile macroeconomic environments or where domestic gas infrastructure is still developing. The Philippines, Ghana, and El Salvador are examples of countries that have recently commissioned FSRUs.

The future of FLNG and FSRUs in emerging markets

Growing role for FLNG

The future of FLNG is bright, with uptake to be shaped by advances in efficiency, modularity, and adaptability. Ongoing research and development to reduce capital and operating costs through standardised designs, use of smaller scale modular liquefaction units, and reduced maintenance requirements will all contribute to the success of FLNG.

Figure 3. Global FSRU fleet growth (2015 – 2030). Based on analysis by Rystad Energy and published in the IGU's World LNG Report 2025.

Flexibility will remain a key driver of FLNG adoption and recent examples of redeployments demonstrate 'proof of concept'. Next-generation vessels are being designed for redeployment across different fields or regions, enabling operators to respond quickly to shifts in global supply-demand dynamics. Integration with carbon management technologies will also enhance environmental performance and align FLNG with decarbonisation goals. In addition, FLNG may evolve to support multi-product platforms, including the liquefaction of hydrogen, ammonia, or bio-derived gases, providing strategic versatility as energy markets diversify.

These technological advances are particularly important for emerging markets, where financial, infrastructural, and regulatory constraints often limit access to conventional onshore liquefaction facilities. Enhanced digital monitoring and predictive maintenance improve operational reliability, mitigating risks in regions with limited technical expertise or emergency response capacity. Collectively, these advances increase the attractiveness, resilience, and strategic value of FLNG for resource-rich developing countries seeking to accelerate participation in global energy markets and economic development.

New markets for FSRUs

As domestic gas production tapers in a number of jurisdictions, many countries are looking to FSRUs to enable flexible importation of LNG to meet energy demand. In more traditional emerging markets with growing electricity demand, FSRUs will continue to offer a flexible solution as economies look to diversify energy supply and enhance energy security. One such example is Brazil and its LNG-to-power strategy, with multiple FSRUs deployed alongside dedicated gas electricity generation facilities. Brazil has also deployed an innovative product in the form of the Sepetiba Bay FSRU, which connects to four power ships enabling 560 MW of electricity generation capacity through an entirely offshore solution. This flexible approach allows LNG import and power generation facilities to be deployed quickly, but also in a way that allows for redeployment once alternative solutions are made available. This can provide the benefits of access to LNG markets without the need to make a permanent commitment to LNG as a source of energy supply.

Conclusion

The global LNG market is entering a period of rapid transformation, characterised by evolving demand patterns, potential short-term oversupply, and emissions reduction pressure. FLNG technology is evolving through modularisation, digitalisation, and multi-product adaptability, increasing its economic viability and strategic relevance for developing countries with offshore gas resources. FSRUs provide a highly flexible, lower-risk mechanism for import-dependent economies to secure LNG supplies, scale capacity in line with uncertain demand, and leverage favourable market conditions in periods of oversupply.

Floating LNG infrastructure, in the form of both FLNG and FSRUs, are a flexible and strategic solution within these dynamics for emerging markets, offering pathways to accelerate participation in the global gas market, diversify supply, and support the shift to lower-carbon energy systems.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.