- within Law Department Performance, Consumer Protection and Wealth Management topic(s)

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

Are unregulated entities or funds the answer?

For non-European banks, the lack of regulatory harmonisation across EU Member States makes cross-border lending into the EU complex, with several Member States (including France and Italy) prohibiting direct lending. The implementation of the CRD VI third-country branch (TCB) licensing requirement on January 11, 2027 will further constrain direct lending into those other Member States which have historically permitted direct lending.

This bulletin explores the possible use of non-bank lending entities and funds as a means of conducting lending activities with corporate borrowers in certain EU jurisdictions and the implications of the new loan origination requirements for funds under AIFMD II in this context.

Background

Lending by EU credit institutions is regulated under the EU capital requirements regime. Under Article 4(1)(1) of CRR (Regulation (EU) 575/2013), "credit institutions" include deposit-taking banks as well as large MiFID investment firms which conduct underwriting and dealing on own account in financial instruments. For an EU credit institution to conduct lending activities, it must have the appropriate authorisation under CRD (Directive (EU) 2013/36).

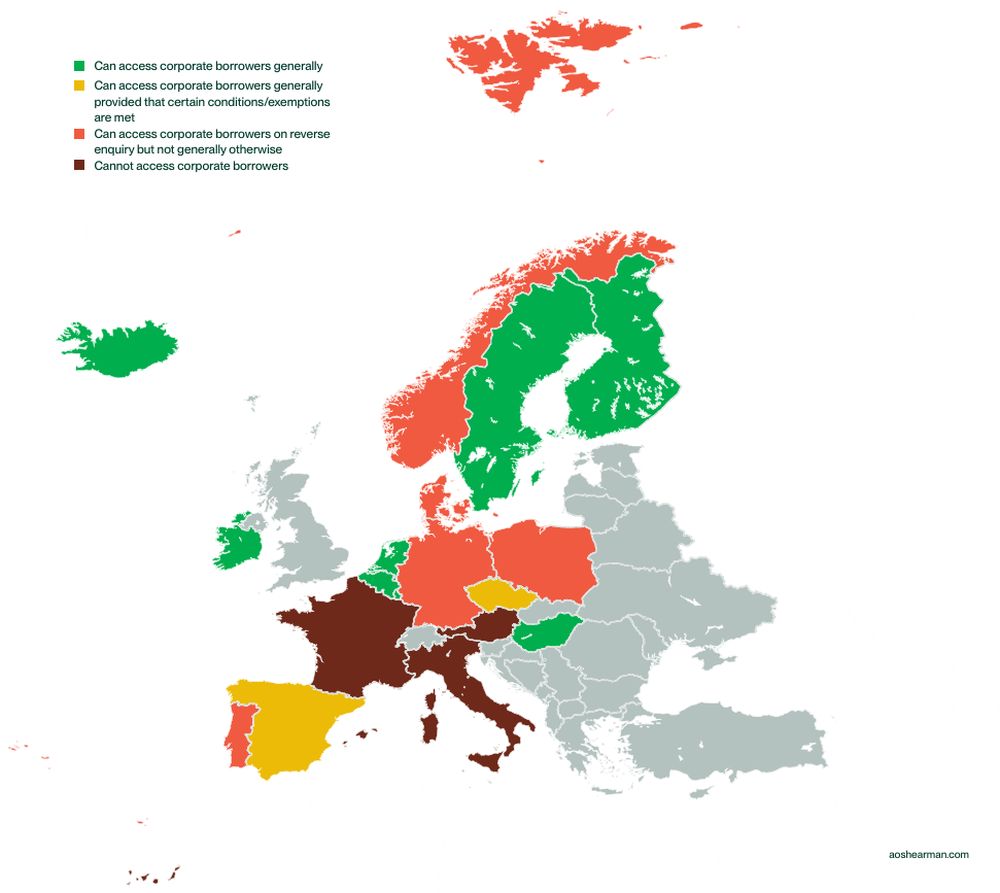

CORPORATE LENDING BY NON-EU BANKS —PRE-CRD VI TCB LICENSING REQUIREMENT

Until now, EU law has been silent on the regulation of cross-border banking services by non-EU banks (i.e., regulated deposit-taking institutions with no place of business in the EU). Certain EU Member States currently prohibit third-country lenders (including, but not limited to, banks) from lending to corporate borrowers without a local licence or branch. Some do so with (broadly) no explicit exceptions (France, Italy); some with exceptions for reverse solicitation (Germany and Portugal) or a "characteristic performance" concept exempting cross-border lending provided the lender itself is not physically present (so there is no lending activity) in the borrower's EU Member State (Luxembourg); and some with hardly any rules (the Netherlands). A very rough map of the restrictions imposed on some non-EU bank lending by the main Member States is below, colour coded to show whether the Member State is very restrictive (dark red), restrictive (red), can access with some conditions or exemptions (yellow), or liberal (green).

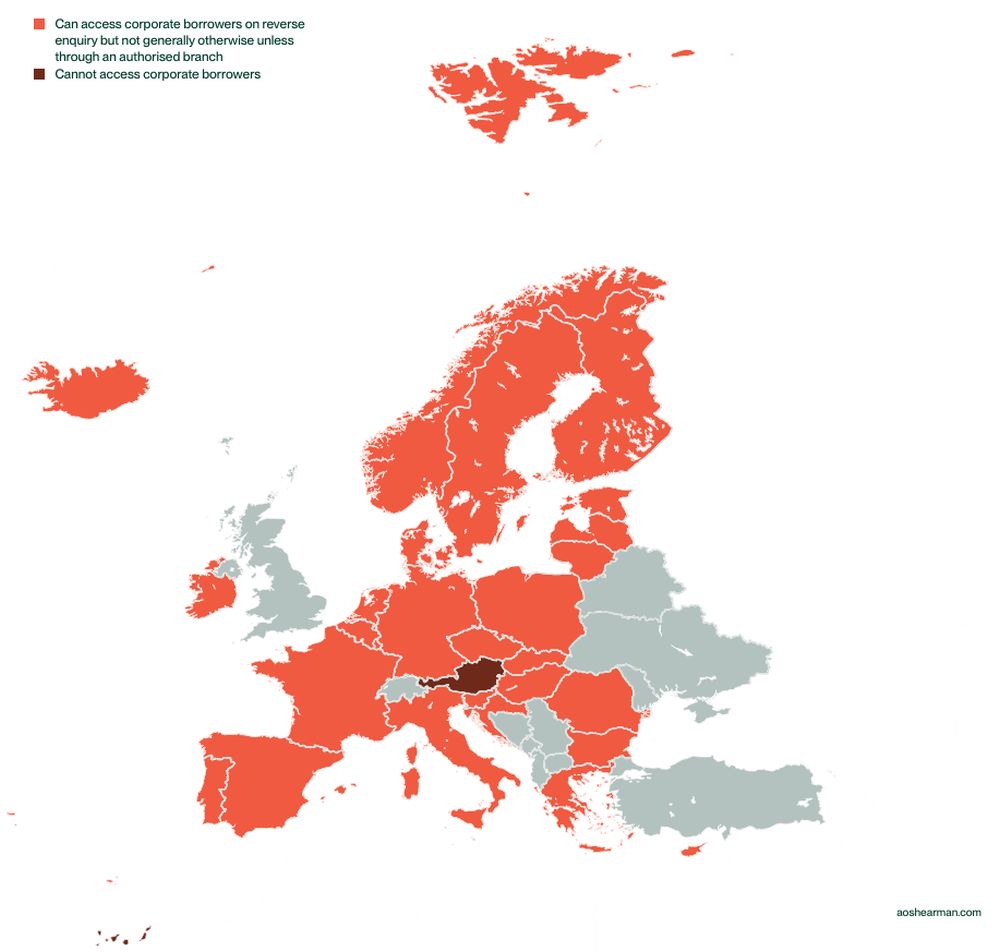

CORPORATE LENDING BY NON-EU BANKS—POST-CRD VI TCB LICENSING REQUIREMENT

CRD VI has introduced a new pan-EU lending restriction in the form of Article 21c. From January 11, 2027, non-EU entities that would, if established in Europe, qualify as "credit institutions" will have to establish an authorised TCB in order to lend to EU corporate and other borrowers, unless an exemption applies.

There are exemptions for cross-border lending that is ancillary to MiFID services, inter-bank cross-border lending, intra-group cross-border lending and cross border lending on the basis of reverse solicitation (discussed further in our client bulletin, CRD VI— European Banking Authority report on direct provision of services from third-country institutions).

There may be further leeway in Member States' interpretation of territoriality, a concept that is not specifically addressed by CRD VI. Luxembourg, for example, is proposing to perpetuate its "characteristic performance" approach to determine where any lending activity is taking place, effectively maintaining some degree of flexibility beside the newly introduced restrictions: this is a point that could still evolve in the course of national legislative processes. Outside of these limited exemptions, and subject to limited grandfathering of transactions agreed by July 10, 2026, non-EU entities conducting any lending into the EU will incur the burden (and expense) of determining whether their activities fall within scope of the TCB requirement, the process of authorisation in an EU Member State if they do, and the ongoing capital, liquidity, governance and other requirements that will sit with TCBs established in an EU Member State. For non-European banks, the map of Europe changes as below.

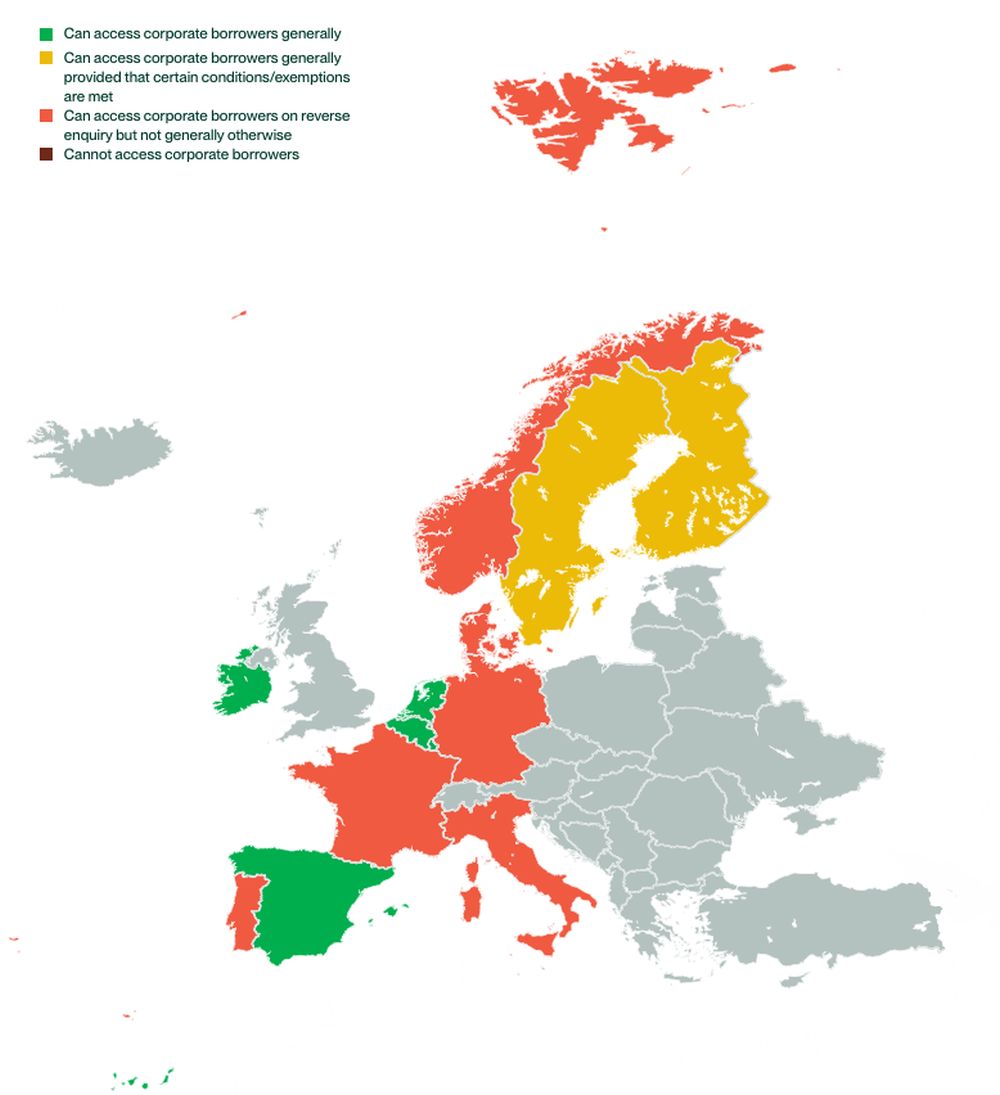

CORPORATE LENDING BY NON-EU NON-BANKS, POST-CRD VI

Significantly, CRD VI's prohibition on lending only covers "credit institutions". As a result, for non-EU non-banks which are not credit institutions, CRD VI does not change their existing position. A rough map for non-EU non-banks (and EU non-banks) lending into certain EU jurisdictions today (and may be expected to be) post-CRD VI is as follows:

Unregulated lending entities—a good idea?

This raises the question whether non-EU banks can restructure their lending activities into non-bank entities to continue their lending activities post-CRD VI implementation into those jurisdictions which have turned red for non-EU bank lending (shown in the second map) but are green or amber for non-EU non-bank lending (as seen in the third map); and, if so, whether they should.

In response to the first of these questions, we consider the answer is a fairly unqualified "yes". The Directive's limited application is intentional: the initial draft of the Directive in relation to the proposed TCB requirements carried a wider prohibition on lending which applied to both non EU banks and non-EU non-banks, but the scope of the regime was reduced as the legislation evolved. Thus far, no national implementation measures have taken a wider scope of application than the Directive. So on its face there is no particular "hard law" bar to a non-EU bank using unregulated non-bank entities to conduct lending into the EU Member States which are turning red for non-EU bank lending—either under EU or local Member State law. For unregulated entities, that leaves only the need to consider— at the EU level—restrictions in Member States, including those that have historically maintained domestic banking monopoly rules preventing banks which are not subject to local bank regulation from lending in their territory, which may persist following the transposition of CRD VI.

As to the second question, concerns tend to arise from several perspectives. The first is the question whether and how the EU authorities are likely to address this approach: is it an unacceptable workaround, or will regulators stamp down on such non-bank lending structures on the basis that they arbitrage EU and Member State domestic law? As yet we have had no particular view on this issue from the EU or from national authorities, but consider it is hard to see a clear legal basis for intervention by the EU or national authorities where banking groups meet their legal obligations. This leaves the only likely avenue for the authorities to be through the supervision of those banking group entities they regulate in the EU—i.e., local subsidiaries or TCBs. We anticipate that banks' risk appetites will likely vary accordingly, with those banks which have no EU presence likely to be very relaxed and considering they are at negligible risk when using non bank lending entities for EU lending; those which are EU-regulated, but not ECB-regulated, being perhaps more at risk, and those regulated directly by the ECB at most risk—albeit that it is unclear what action the ECB could take to sanction an EU bank or branch for its non-EU affiliates' lawful activities. Firms should also be aware that breaches of domestic banking monopoly rules can attract criminal sanctions in certain EU jurisdictions (e.g., France), which may apply even without an EU nexus, so lending activity in each EU Member State would need to be considered on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis.

We also note that some banking groups (both EU and non-EU) use unregulated non-bank lending entities today, and think that those that do are unlikely to change their approach as a result of CRD VI. So there are precedents.

Questions will also arise from the lead or local regulator(s) of a non-EU bank group when considering an unregulated affiliate lending structure. These will likely include the attitude of the home state regulator of the bank to establishing and using unregulated lending entities; implications for risk management and control of the activities of the non-bank lending entity; and capital and liquidity considerations (how to get funding into the entity without creating capital or liquidity frictions).

The EU giveth, and the EU taketh away: are alternative investment funds as lending entities a better idea?

At the same time as prohibiting cross-border lending by third-country banks, the EU is also facilitating lending by alternative investment funds (AIFs, also simply referred to as "funds" in this paper). Following national law measures implemented after the Global Financial Crisis, a number of Member States which had banking monopoly rules provided exemptions to those rules to permit lending by funds—albeit sometimes only by their domestic funds, and sometimes by both domestic and other EU Member State funds—impending changes to the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (under Directive (EU) 2024/927 - AIFMD II) contemplate a harmonised framework for cross-EU lending through the recognition of loan origination funds.

This may present an avenue for non-EU banks to carry out cross-border lending to EU corporates, using an EU authorised alternative investment fund manager (EU AIFM) to manage an EU fund where under that structure the EU AIFM can delegate portfolio management (i.e., lending decision making) back to the non-EU bank or an affiliate asset manager.

AIFMD II

AIFMD II came into force on April 15, 2024 and must be implemented by Member States by April 16, 2026. It provides rules around loan origination by funds, partly to enhance access to finance by EU businesses and partly to address potential prudential risks associated with unrestricted lending by funds. The new AIFMD II loan origination requirements are discussed in detail in our bulletin, AIFMD II: Unveiling the timeline for the new loan origination regime.

AIFMD II adds "originating loans on behalf of an AIF" to the list of activities that an EU AIFM is permitted to engage in on a cross-border basis. Loan origination is defined broadly—it includes both: (i) direct lending by a fund; and (ii) indirect lending through a third party or SPV on behalf of the fund, or on behalf of an EU AIFM in respect of a fund, where the fund or EU AIFM is involved in structuring the loan or defining its characteristics, and gains exposure to it.

A FUNDS "LENDING PASSPORT"?

Given the (currently unchanged) position for non-bank lenders under CRD VI, a fund could only represent a better solution from a regulatory perspective if it enabled greater market access than other non-bank lenders or resolved any of the other potential difficulties faced by non-EU banks with the impending TCB requirements. Tax considerations could, depending on the circumstances, also make loan origination via a fund more attractive. The real differentiator would be unfettered access to EU corporate borrowers—a funds "lending passport" to lend on a pan-European basis. No passport exists under the current regime: the key question is whether the implementation of AIFMD II results in one.

AIFMD does not include a formal passporting regime for cross-border lending, but Recital 13 of AIFMD II states (our emphasis):

"common rules should also be laid down to establish an efficient internal market for loan origination by AIFs, to ensure a uniform level of investor protection in the Union, to make it possible for AIFs to develop their activities in all Member States and to facilitate access to finance by Union companies..."

It seems the Commission has anticipated that Member States will implement AIFMD II in a way which recognises the rights of a fund with an EU AIFM to originate loans cross-border—effectively overriding any pre-existing banking monopoly rules. A comparable approach proved necessary a few years ago in connection with Regulation (EU) 2015/760 on European long-term investment funds (the ELTIF Regulation). Although directly applicable throughout the EU, the ELTIF Regulation nonetheless required certain EU Member States to adjust their domestic legal frameworks to accommodate—and practically enable—ELTIFs' cross-border lending activities. ELTIFs therefore effectively benefit from a form of lending passport (e.g., in France), subject to the constraints of the ELTIF Regulation. It is, however, of limited use to non-EU AIFMs given ELTIFs must be EU AIFs operated by EU AIFMs.

As transposition legislation is passed it will become clear whether Recital 13 is interpreted to permit cross border loan origination. At this stage, grey areas remain regarding the scope of such a lending passport. While there is a reasonable degree of certainty that EU AIFMs managing EU AIFs could rely on such a passport, material uncertainty persists across Member States on several scenarios where there may be no harmonised approach, including: (i) whether a non-EU AIF managed by an EU AIFM can rely on the lending passport (given that AIFMD II requirements—particularly those on loan origination— apply to the EU AIFM and only indirectly to the AIF as a result of this AIFM-focused framework); (ii) whether the passport would extend to all AIFs or only to those qualifying as "loan origination funds" under AIFMD II; and (iii) whether unregulated SPVs owned by an AIF within the scope of AIFMD II, which are often needed to mitigate withholding tax imposed in non-bank lending situations, may lend cross-border as the 'lender of record' within the EU and, if so, under which conditions (capital/voting control requirement from the AIF over the AIF; location of the SPV, etc).

So far, there does not appear to be an intention, by virtue of Recital 13 or otherwise, to activate the EU loan origination passport for non-EU AIFMs, meaning national banking monopoly rules or other regulatory frameworks restricting non-bank lending activities will continue to apply in place of the AIFMD II loan origination provisions (with the exception of some disclosure requirements on loan origination, which do capture non-EU AIFMs). Certain EU Member States may nevertheless permit non EU AIFMs to engage in loan origination under their own national regimes, which again will require monitoring on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis.

REACHING THE PARTS OTHER VEHICLES CANNOT REACH?

If a loan origination passport for funds does emerge – acknowledging its scope is currently uncertain – what would be the pros and cons of a fund structure versus an unregulated lending vehicle for prospective third-country lenders?

Wider EU borrower access: The clear benefit of a passported loan fund would be EU-wide corporate borrower access (excluding consumer lending, for which national restrictions may still be imposed). At present this will only be an option for EU-authorised AIFMs managing EU AIFs. However, even in the absence of a full passport for non-EU AIFMs, the more permissive national regulatory regimes of certain Member States (as shown in the map above) may permit easier ongoing access when compared to the impending CRD VI TCB requirements.

Regulatory capital treatment: A further collateral benefit would be that (at least in the UK) funds can obtain look through treatment for regulatory capital purposes—so are a capital-efficient mechanism for downstreaming capital. A UK bank lending via a fund, for example, would not be impacted by UK CRR capital requirements at the fund level and the look-through approach would allow the bank to treat the fund's underlying exposures as if they were directly held by it. This is preferable (from a capital perspective) to bank lending via a subsidiary, which (again, in the UK) would trigger capital requirements at both the subsidiary and parent level.

DOWNSIDES

However, a number of other considerations would also come into play in the event of passporting or enhanced Member State requirements for non-EU sponsors:

Collective Investment Undertaking (CIU) status: Under AIFMD, the fund as an AIF must have the characteristic of being a CIU. ESMA has prepared guidance on the concept of a CIU specifying that AIFs should "raise capital from a number of investors". This raises the question of whether a single investor (i.e., a third-country bank) could use the fund structure to originate loans in the EU. ESMA's guidance says that if national rules do not prevent an entity from raising capital from a number of investors, it should be deemed to do so, even if it in fact only has a single investor. This guidance, however, was given with master feeder funds in mind as opposed to a single bank investor fund structure. It is therefore likely a question of individual EU Member State implementation as to whether a sole investor structure can qualify as an AIF, noting that some jurisdictions adopt a more flexible approach to this issue or a de minimis second investor can be admitted.

Obligations of an AIFM: The establishment and ongoing operations of an authorised EU AIFM carries operating costs. These include substance requirements (most notably the appointment of at least two senior managers based in the EU Member State where the EU AIFM is authorised and the retention of adequate resources to run the business), the requirement to provide portfolio and risk management services, as well as operational and reporting requirements including publication of annual reports for each AIF under management, disclosure of extensive information to investors regarding the AIF's investment strategy and operations, reporting to national supervisors and the establishment of policies, procedures and processes to assess credit risk and monitor the credit portfolio and processes to assess credit risk and monitor the credit portfolio.

An alternative option would be for a non-EU sponsor to employ a third-party EU AIFM to carry out these functions under a so-called "rent an AIFM" or "white label" model, with the AIFM in turn delegating portfolio management back to the non-EU bank or its asset management affiliate, provided the delegate holds a portfolio/asset management licence in its home jurisdiction and appropriate cooperation arrangements are in place between the competent regulators of the relevant jurisdictions at stake. Luxembourg, for example, has a well-developed third party AIFM market whereas other jurisdictions—such as France—are now permitting this type of set up. This appointment arrangement would reduce costs and allow quicker time to market. Existing guidance at the EU level gives no indication that such a structure would cut across the CRD VI TCB requirements at this stage.

Risk management: Under AIFMD II, EU AIFMs must establish policies, procedures and processes to assess credit risk and to administer and monitor their credit portfolio. Those must be kept up to date and reviewed at least once a year.

Risk retention: Under AIFMD II, a fund must retain 5% of the notional value of each loan that it has originated and transferred to third parties for a specified period of time—for loans with a maturity of up to eight years and loans granted to consumers, the retention period is the maturity of the loan; for other loans, the retention period is at least eight years. There are exceptions to this in certain circumstances.

These include where:

- the EU AIFM starts to sell the fund's assets to redeem units or shares as part of the liquidation of the fund;

- a disposal is necessary to comply with EU sanctions or product requirements (e.g., when retaining the originated loan would breach investment or diversification requirements);

- the disposal is necessary to allow the EU AIFM to implement the fund's investment strategy in the best interests of investors; and

- the sale of the loan is due to a deterioration in the risk associated with the loan. Recital 20 specifies this may occur where the borrower's situation has changed in the event of merger or default, if the fund's investment strategy is not to manage distressed assets.

Concentration limits: Under AIFMD II, the notional value of loans originated to a single borrower must not exceed in aggregate 20% of the AIF's capital where the borrower is a "financial undertaking" (including credit institutions, financial institutions, insurance undertakings, reinsurance undertakings, MiFID investment firms or MiFID financial institutions and mixed financial holding companies), an AIF, or a UCITS.

Prohibition of the "originate-to-distribute" strategy: AIFMD II prohibits an originate-to-distribute strategy, whether that is the exclusive strategy or just a part of the fund's investment strategy. There are clear disadvantages to this, including restriction of the lender's ability to reduce concentration of its credit risk and to free up capital for new lending when desired.

Leverage caps: Under AIFMD II, loan-originating funds (i.e., where the fund's strategy is mainly to originate loans or originated loans make up at least 50% of its NAV) must comply with a leverage limit of: (i) 175% if they are open-ended; or (ii) 300% if they are closed ended. National supervisors may impose stricter limits, however. AIFMD II provides further specifications around the calculation of the leverage limit.

Conclusion

The case will not be made for loan funds as a substitute for third-country bank lending into the EU until the outcome of the transposition process for AIFMD II is known. Ongoing EU work on non-bank financial intermediation should also be closely monitored, as it could ultimately affect any AIFMD II lending passport.

Nevertheless, AIFMD II may provide an avenue for third country banks to explore as they work out how they may lend into the EU without the substantial frictional costs of local branches or intermediating lending through an EU bank subsidiary arising from the impending CRD IV TCB requirements.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.