- within Antitrust/Competition Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Advertising & Public Relations, Banking & Credit and Technology industries

- within Antitrust/Competition Law, Transport, Media, Telecoms, IT and Entertainment topic(s)

- with Inhouse Counsel

- in Turkey

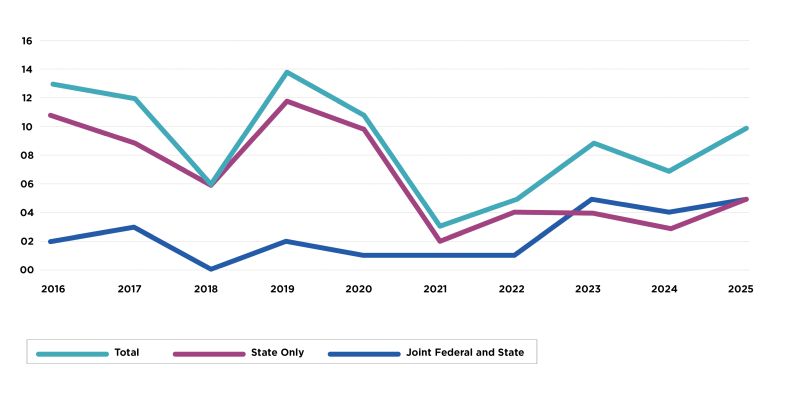

In recent years, the initiation of state enforcement actions and settlements for alleged antitrust violations has rebounded from a lull in 2021 and 2022.1 In 2025, the states collectively filed actions or announced settlements in five single-state matters, participated or joined with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in four other matters and joined with the Antitrust pision of the Department of Justice (DOJ) in another matter. In contrast, in 2021, the states filed just one action alongside the DOJ, plus three actions on their own, and in 2022 they filed one action together with the FTC and five on their own.2 The number of actions remains below a recent high-water mark set in 2019, when the states collectively initiated 12 actions or settlements, joined with the FTC in one other action, and joined with DOJ in another action.

It would be a mistake to underestimate state involvement in policing the antitrust laws, on both a local and national level. The state attorneys general remain strongly committed to antitrust enforcement.3,4 Moreover, two recent developments have thrust state antitrust enforcement into the spotlight. The first is the adoption by Colorado and Washington of the Uniform Antitrust Pre-Merger Notification Act. The second is California's adoption of a law, effective January 1, 2026, that generally prohibits shared pricing algorithms that may be used to restrain trade.

Traditional State Enforcement of State Antitrust Laws

The National Association of Attorney General (NAAG) has hosted a website devoted to listing and detailing state antitrust enforcement and settlement activity.5 On its website, the NAAG declares—

State attorneys general have enforced the antitrust laws since the nineteenth century, but their efforts increased dramatically after 1990, when the states formed the NAAG Multistate Antitrust Task Force. Through the Antitrust Task Force, state and territory attorneys general work closely together to protect their consumers by bringing antitrust cases in a wide variety of industries, including pharmaceuticals, health care and agriculture. Inpidual attorneys general also prosecute bid-rigging on public contracts of all kinds.6

State antitrust enforcement and settlement activity has fluctuated over the years, and recently appears to have recently rebounded, while still falling short off its peak activity in 2019. The following graph charts state enforcement actions and settlements initiated during the years 2016 through 2025 based on the matters collected in Appendix I:

The types of alleged antitrust violations addressed by state enforcers run the gamut of traditional antitrust enforcement.7 They include monopolization, merger and acquisition review, big-rigging, price manipulation, pay-for-delay and product hopping, and anti-poaching and non-solicitation. Recently, there have been state antitrust actions with an anti-ESG flavor. One case brought antitrust to bear on coal industry investment, another on truck manufacturing and clean air compliance and, most recently, a third on the recommendations of the large proxy advisory services.

As one may expect, state actions, particularly single state enforcement, are often directed towards local issues, such as the combinations of regional health care providers or bid-rigging on government construction projects. The states tend to join forces with the federal agencies where the antitrust concerns are national in scope, for example challenges to airline mergers and joint ventures, monopolization cases in the tech sector, and combinations of large healthcare insurers. But this is not always the case. One large case where the states are charting their own course is a suit against 36 pharmaceutical companies by 45 states and four territories for price manipulation of generic dermatological drugs, a case that has been winding its way through federal courts since 2020 and recently survived summary judgment.8

Notwithstanding fluctuations in the initiation of state antitrust matters, state antitrust enforcement, in the words of one director of a state antitrust pision, "has never been stronger."9 It has also been remarked that in the last couple of years, the state attorneys general offices have been increasing their staff numbers in antitrust pisions.10 Practitioners are therefore advised to be alert to possible state antitrust involvement, and in appropriate circumstances to approach the offices of the state attorneys general on antitrust sensitive transactions.11

Uniform Antitrust Pre-Merger Notification Act

The adoption in final form in 2024 of the Uniform Antitrust Pre-Merger Notification Act (UAPNA) by the National Conference of Commissioners of Uniform State Laws is one indicator of the continuing focus of the states on antitrust concerns. Thus far, laws modeled on the UAPANA have been adopted by Washington state, effective July 27, 2025, and Colorado, effective August 6, 2025.12 Perhaps not coincidentally, it was these two states that sued separately from the FTC in 2024 to block the Kroger-Albertsons supermarket chain merger.

The Prefatory Note to the UAPNA observes that:

State Attorneys General (AGs) also have a legal right to challenge anticompetitive mergers, both under the federal Clayton Act and their own state antitrust laws. See California v. American Stores Co., 495 U.S. 271 (1990). States often play an important role in merger investigations and challenges, either in parallel with the federal agencies, or on their own.

In explaining the rationale for the UAPNA, the drafters note that the state AGs do not have automatic access to the Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) premerger notification reports filed with the federal antitrust agencies. The AGs in most cases do have the right to subpoena HSR filings, but it is time consuming and cumbersome to do so, and by the time AGs obtain access to HSR filings, the process of investigating and negotiating remedies to a proposed transaction is often far along. The UAPNA is intended to balance the interests of the states in timely obtaining premerger information, with the concern of the business community about being subject to conflicting state and federal premerger notification regimes.

The principal features of the UAPNA are:

- A requirement to file a copy of the HSR form with an adopting state contemporaneously with the federal filing, if either (i) the filer has its principal place of business in the state, in which case the filer must include all additional filed materials; or (ii) the filer and entities under its control had annual net sales of goods and services in the state involved in the transaction of at least 20% of the then applicable minimum HSR filing threshold, commonly referred to as the size-of-transaction test and currently $126.4 million, in which case the filer must provide the additional materials upon request.

- A requirement to maintain the confidentiality of the HSR form and any additional materials, and of the transaction itself, provided that a state is permitted to share the form and other materials with the federal agencies and any state that has adopted the UAPNA or a substantially similar statute that includes confidentiality provisions at least as protective as the UAPNA. Before the documents are provided to another state, at least two business days' notice must be given to the filing party.

- A provision for a per diem penalty for non-compliance; both Colorado and Washington State have adopted the suggested daily amount of $10,000.

Separately, 16 states, including Colorado and Washington, thus far have enacted statutes providing for premerger notification of mergers in the healthcare space.13 In contrast to the UAPNA, these statutes are not uniform. For example, the timing for filing a notification can range from 30 days to 180 days prior to the closing date of the transaction. The filing criteria and notification requirements also vary significantly from state to state. What these statutes have in common with the UAPNA is the interest of the states in receiving timely notification of pending transactions that may have antitrust ramifications in their jurisdictions.

California Algorithmic Pricing Law

California has recently become the first state to pass non-sector specific legislation addressing potential antitrust violations arising out of AI-driven pricing.14 The legislation, which was signed into law on October 6, 2024 and went into effect on January 1, 2026, amends the Cartwright Act, California's antitrust statute. It has two operative provisions, reading as follows:

- It shall be unlawful for a person to use or distribute a common pricing algorithm as part of a contract, combination in the form of a trust, or conspiracy to restrain trade or commerce in violation of this chapter.

- It shall be unlawful for a person to use or distribute a common pricing algorithm if the person coerces another person to set or adopt a recommended price or commercial term recommended by the common pricing algorithm for the same or similar products or services in the jurisdiction of this state.

The term "common pricing algorithm" is broadly defined as:

any methodology, including a computer, software, or other technology, used by two or more persons, that uses competitor data to recommend, align, stabilize, set, or otherwise influence a price or commercial term.

The statute is vague as what constitutes use of a pricing algorithm in restraint of trade. For example, the statute does not address the type of data that an algorithm may use in violation of the statute—and hence does not distinguish between public and non-public data. However, it is possible that an algorithm that feeds only on public data would not violate the statute. Recent federal enforcement action has taken issue with the use of non-public data provided by competitors in pricing programs, but not public data. In the Department of Justice's settlement with RealPage, Inc., a provider of revenue management software in the multifamily rental housing industry, RealPage agreed that it would "[c]ease having its software use competitors' nonpublic, competitively sensitive information to determine rental prices in runtime operation." ,

Also open to question is whether the parallel use by competitors of a common algorithmic pricing tool that relies only on public data would violate the California statute. In the recently decided Gibson v. Cendyn Group, LLC, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit held that it was not a violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act for competing Las Vegas hotels to each purchase a license to use the same price recommendation software program, in the absence of an allegation of agreement among the hotels. Whether multiple contracts with a common vendor of AI pricing software utilizing only public data would constitute a "contract, combination in the form of a trust, or conspiracy to restrain trade or commerce" under California law is left for the California courts to decide.

Conclusion

The states continue to be active in antitrust enforcement both on the litigation and legislative fronts. The initiation of state action to enforce the antitrust laws has rebounded from its low in 2021 and 2022. The states show no sign of tamping down the resources of their attorney general offices devoted to antitrust. Adoption of the UAPNA, which would give the states timely access to HSR filings, has begun, though it remains to be seen whether other states will follow the lead of Colorado and Washington and avail themselves of this tool. California has jumped out in front by incorporating in its antitrust statute a general prohibition on the use of algorithmic pricing in restraint of trade, albeit with contours that are unclear at least for the moment. Parties considering transactions and other activity with antitrust sensitivities are therefore advised not to limit their sights to the federal antitrust agencies alone. Particularly in situations with regional impact, but also in matters of more general reach, the enforcement agendas of the states may also need to be taken into account.

Footnotes

1. See Appendix I for a summary of state antitrust actions and settlements from 2016 to 2025. Appendix I is based primarily on the National Association of Attorneys General (NAAG), State Antitrust Litigation and Settlement Database Results. See note 5. This database is incomplete for 2025 and has been supplemented in Appendix I from other sources. There is no assurance that all state actions and settlements in 2025 have been identified. There is also no assurance that the NAAG database itself is complete for prior years, but no attempt has been made to conduct a search of other sources for those years.

2. This decline in new case initiations may have been influenced by the pandemic or by a focus on a smaller number of large monopolization cases.

3. See National Association of Attorneys General, State Antitrust Litigation and Settlement Database; available at https://www.naag.org/issues/antitrust/state-antitrust-litigation-and-settlement-database/.

4. Indicative of federal recognition of the important role played by the states in the enforcement of the antitrust laws is the State Antitrust Enforcement Venue Act of 2021, passed as part of the 2022 omnibus spending bill and signed into law on December 29, 2022. The Act exempts antitrust actions brought by states in federal court from being transferred to a single district, similar to the exemption available for federal antitrust actions, in an effort to prevent state antitrust defendants from moving to consolidate their cases in a more favorable venue. See 28 U.S.C. 1407(g).

5. See National Association of Attorneys General, State Antitrust Litigation and Settlement Database Results; available at https://www.naag.org/issues/antitrust/state-antitrust-litigation-and-settlement-database/results..

6. See note 3.

7. See Appendix I for generic references to the matters referred to in text. For the identification of the matters collected in the NAAG database, a description of the matters, their resolution or status, and certain related case documentation, see note 5.

8. Currently, Connecticut et al. v. Sandoz, Inc. et al., No. 3:20-cv-00802 (D. Ct.). The case was originally filed in the District of Connecticut, transferred to the Eastern District of Pennsylvania and then retransferred back to the Connecticut federal court. The amended complaint filed in 2021 consists of 609 pages. On October 31, 2025, in a 130-page decision, the court denied the defendants' motion for summary judgment on grounds of laches and statute of limitations. The case is one of three pending multi-state cases in which the states have sued numerous drug manufacturers.

9. "Roundtable Discussion with State Enforcers," Antitrust Magazine (Spring 2025) (remarks of David Sonnenreich, Director, Antitrust Division, Utah Attorney General's Office).

10. Id. (remarks of Elizabeth Odette, Manager, Antitrust Division, Minnesota Attorney General's Office and chair of the Multistate Antitrust Task Force of the National Association of Attorneys General).

11. See "Panel, Defense Views on State Enforcement," Antitrust Magazine (Summer 2025). Among other matters addressed by the panel, it was noted that the states have pre-litigation investigatory authority that can place a substantial burden on the recipients of CIDs and subpoenas. The panelists also discussed circumstances in which it would be advisable to reach out to the state attorney general's office, and the pros and cons of doing so.

12. Other states with pending bills for the adoption of the UAPNA are California (inactive), Hawaii and West Virginia, as well as Washington, D.C. Bills for this purpose were introduced in Nevada and Utah, but failed to pass. A comprehensive antitrust bill pending in New York, which if adopted would be referred to as the "Twenty-First Century Anti-Trust Act," would require "any person conducting business in [the] state" to provide the attorney general with any filing under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act at the same time as the filing is made with the federal antitrust agencies. See https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2025/S335.

13. The states that have adopted healthcare premerger statutes are: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont and Washington.

14. New York has recently enacted an amendment to its antitrust statute, the Donnelly Act, prohibiting the use of algorithmic programing to set residential rental rates. Specifically, new section 340-B to the NY General Business Law makes it unlawful to "set or adjust rental prices, lease renewal terms, occupancy levels, or other lease terms and conditions in one or more of their residential rental properties based on recommendations from a software, data analytics service, or algorithmic device performing a coordinating function." The law also makes it unlawful for owners or managers of residential properties not to compete, including by the use of such software and the like. Similar legislation has been introduced in other states.

Municipalities have also enacted ordinances prohibiting the use of algorithmic pricing for residential rental units using non-public data. See New San Francisco ordinance bans algorithmic rent pricing tools (September 4, 2024); available at https://www.nbcbayarea.com/news/local/san-francisco/ordinance-bans-algorithmic-rent-pricing-tools/3643161/; Councilmember O'Rourke's Algorithmic Rental Price-Fixing Ban Passes [Philadelphia] Council, Heads to Mayor Parker's Desk (October 24, 2024); available at https://phlcouncil.com/councilmember-orourkes-algorithmic-rental-price-fixing-ban-passes-council-heads-to-mayor-parkers-desk/; Minneapolis council passes bill to ban algorithmic rental price fixing (March 27, 2025); available at https://www.fox9.com/news/minneapolis-council-passes-bill-ban-algorithmic-rental-price-fixing; Santa Monica Bans Algorithmic Rental Pricing Software After Wildfire Crisis (July 2, 2025); available at https://smdp.com/government-politics-2/santa-monica-bans-algorithmic-rental-pricing-software-after-wildfire-crisis/; Portland bans use of rental pricing algorithms (November 20, 2025); available at https://djcoregon.com/news/2025/11/20/portland-bans-use-of-rental-pricing-algorithms/.

New York has also recently enacted its own form of general algorithmic pricing statute, although it is not directed towards antitrust concerns. The Preventing Algorithmic Pricing Discrimination Act, codified at NY General Business Law §349-a, requires anyone who advertises or promotes "personalized algorithmic pricing using consumer data specific to a particular individual" to include disclosure to that effect. See Press Release, Consumer Alert: Attorney General James Warns New Yorkers About Algorithmic Pricing as New Law Takes Effect (November 5, 2025); available at https://ag.ny.gov/press-release/2025/attorney-general-james-warns-new-yorkers-about-algorithmic-pricing-new-law-takes.

15. The legislation adds Sections 16729 and 16756.1 to the state's Business and Professions Code. In addition to addressing AI-driven pricing, the statute also reduces certain pleading standards in antitrust cases.

16. See Press Release, Justice Department Requires RealPage to End the Sharing of Competitively Sensitive Information and Alignment of Pricing Among Competitors (November 24, 2025); available at https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-requires-realpage-end-sharing-competitively-sensitive-information-and. The Department of Justice earlier entered into a settlement agreement with Greystar Management Services LLC, the largest landlord in the United States and a user of RealPage software, containing similar terms. See Press Release, Justice Department Reaches Proposed Settlement with Greystar, the Largest U.S. Landlord, to End Its Participation in Algorithmic Pricing Scheme (Augst 8, 2025); available at https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-reaches-proposed-settlement-greystar-largest-us-landlord-end-its.

17. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals' decision in Gibson v. Cendyn Group, LLC, D.C. No. 2:23-cv-001400MMD-DJA (Aug. 15, 2025) is somewhat instructive on this point as well. While the point was not a focus of the court's discussion, the court did note that there was no allegation that the pricing program at issue there "pools, shares, or uses the confidential information provided by a given [defendant] into the pricing recommendations it generates for any other [defendant]."

18. See the preceding note. The plaintiffs in this case were a putative class of renters of Las Vegas hotel rooms, who alleged that room rates increased after the hotels began to use the pricing program. A request for rehearing en banc has been denied.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.