On July 15, 2025, Judge Evelyn Padin of the District of New Jersey denied Novartis's motion for preliminary injunction, which would have blocked MSN Laboratories Pvt. Ltd. from selling a generic version of Novartis's Entresto based on alleged trade dress infringement. Her decision could have significant implications for trade dress claims in the pharmaceutical context.

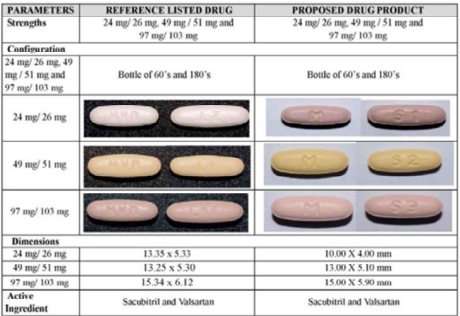

Novartis's trade dress case is related to a wider regulatory/patent dispute regarding MSN's abbreviated new drug application for a generic version of Entresto, Novartis's blockbuster drug that has become the leading branded medication for the treatment of heart failure. Entresto comes in three different dosage strengths, each of which is marked with "NVR" and has a distinct color/size/shape combination. MSN's proposed generic, which it intends to market under the name "Novadoz" will also have three dosages, each of which will be marked with "M" and have a similar color, size, and shape to the corresponding dosage of Entresto:

Judge Padin previously granted a motion for PI from Novartis, concluding that it was likely to succeed on its trade dress claim. After MSN appealed her grant of PI to the Third Circuit, however, Judge Padin indicated that she was contemplating sua sponte reconsideration of her earlier decision. MSN's appeal meant that Judge Padin no longer had jurisdiction to reconsider, but Judge Padin ultimately granted MSN's motion to stay the PI pending appeal. In doing so, she acknowledged that her previous opinion had incorrectly determined that Entresto's color/size/shape were non-functional and therefore protectable as trade dress.1The Third Circuit issued a limited remand, and Judge Padin's most recent decision addresses Novartis's motion for PI and for an injunction pending appeal.

Echoing her previous opinion on MSN's motion to stay, Judge Padin found that Novartis was not likely to succeed on the merits of its trade dress claim because Entresto's features "are functional, have not acquired secondary meaning, and consumers are not likely to confuse the source of Novartis's and MSN's tablets based upon trade dress."2

In terms of functionality, Judge Padin noted that pharmaceutical trade dress is unique in that "modern generic drugs like MSN's must meet stringent FDA standards, allaying trade dress policy concerns that seek to protect manufacturers and consumers from relying on 'the overall look of a product' to indicate quality."3Ultimately, Judge Padin found that the different colors, sizes, and shapes of Entresto tablets were functional because they help patients determine which dosage strength they are taking. She further credited evidence that the tablets' sizes and shapes increase patient administrability, decrease manufacturing costs, and reduce the difficulty of swallowing.

Because Entresto's trade dress related to the appearance of the actual drug product rather than its packaging, Judge Padin analyzed secondary meaning under the more difficult standard for "product configurations." She found that, although some evidence showed an association between Entresto's appearance and its ingredients or effects, there was little evidence of association between Entresto's appearance and Novartis as the source of the drug. Judge Padin contrasted Entresto's marketing with that of red-soled Louboutin shoes and AstraZeneca's "Purple Pill," (Prilosec) the marketing for both of which created an association between a specific product color and the brand name (i.e., source) behind that product.

Judge Padin also found a low likelihood of confusion based on Entresto's package showing the Entresto trademark. Because all three trade dress factors cut against Entresto, she found that Novartis had failed to show a likelihood of success. Disposing of the other PI factors in short order, she denied Novartis's motion for injunctive relief.

The most recent Entresto trade dress decision indicates that the color, size, and shape of drugs are generally less likely to constitute protectable trade dress. Brand-side manufacturers looking to shore up their drugs' trade dress may want to avoid specific color/size/shape combinations for different dosages, because that could lead to a finding of functionality. To establish secondary meaning, such manufacturers' marketing should establish a link between a drug's appearance and its source (e.g., like AstraZeneca's "Purple Pill") – not just between its appearance and the specific drug. But overall, brand manufacturers should know that, because a drug's appearance is likely a "product configuration," establishing secondary meaning will generally be more difficult than for a drug's packaging. On the generic side, Judge Padin's decision offers potentially potent arguments to support the ability to mimic a brand drug's appearance, particularly in light of drug-specific policy concerns.

On July 21, the Third Circuit issued a single-page order denying Novartis's motion for an immediate administrative injunction and injunction pending appeal. Without an injunction in place, Novartis's trade dress allegations cannot block MSN from marketing its generic drug pending resolution of the litigation.

Footnotes

1. See Novartis AG v. Novadoz Pharms. LLC, No. 25CV849 (EP) (JRA), 2025 WL 1482417, at *3 (D.N.J. May 22, 2025).

2. See Novartis AG v. Novadoz Pharms. LLC, No. 25CV849 (EP) (JRA), 2025 WL 1937082, at *3 (D.N.J. July 15, 2025).

3. Id. at *4.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]