- within Antitrust/Competition Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Pharmaceuticals & BioTech and Retail & Leisure industries

General Overview

On April 22, 2025, the Federal Circuit ruled in In re Bonnie Iris McDonald Floyd1 that a design patent application could not claim priority to an earlier-filed utility patent application for lack of sufficient written description, affirming a decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board.

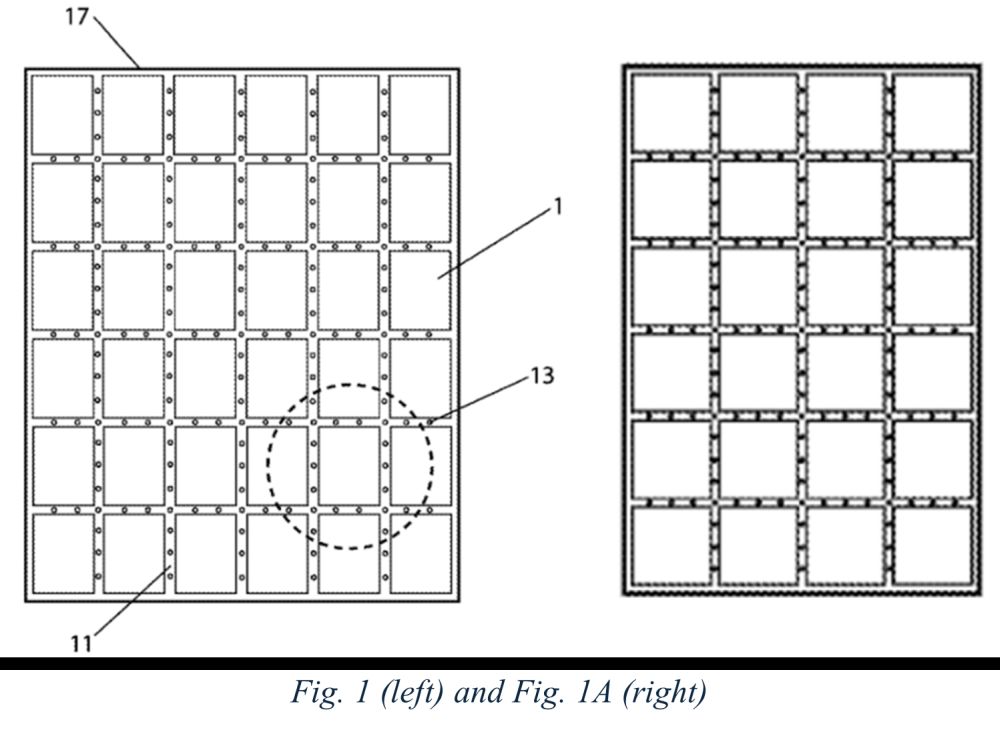

On January 23, 2016, Floyd filed a U.S. utility patent application directed to a cooling blanket featuring "an integrated ventilation system" and "multiple, sealed compartments." Two embodiments of the claimed invention were described as depicted in Fig. 1 and Fig. 1A of the application, reproduced below. The embodiment in Fig. 1 presents a six-by-six array, while the embodiment in Fig. 1A presents a six-by-four array of compartments.

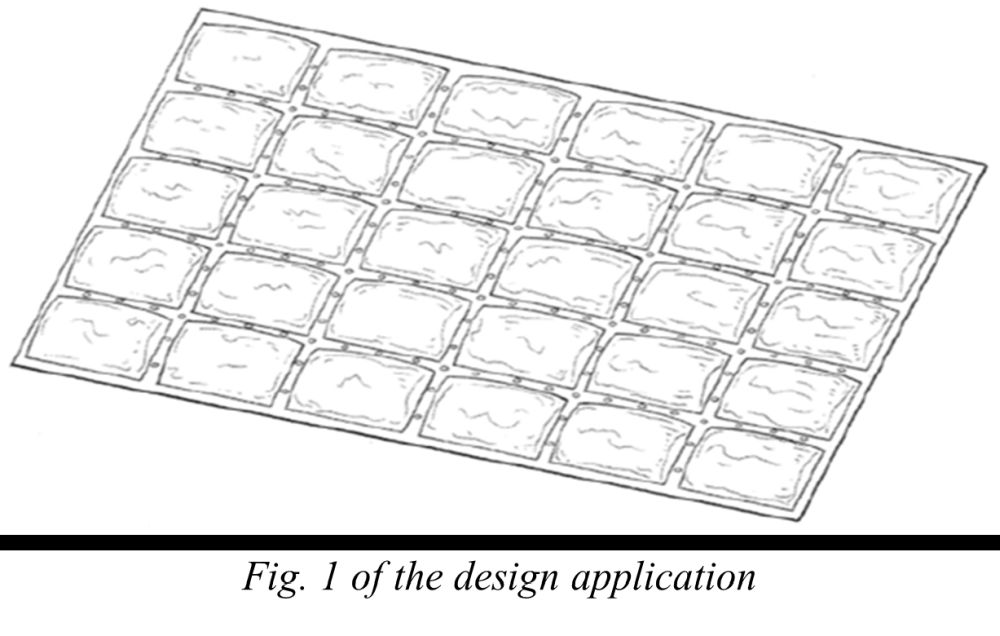

Fourteen months later, Floyd filed a U.S. design patent application claiming a six-by-five array as an ornamental design shown below. The design application claimed priority, i.e., the benefit of the earlier filing date, of the utility application. The examiner rejected the priority claim under 35 U.S.C. § 112 on the grounds that the earlier-filed utility application lacked written description for the design claimed in the later-filed design application. As a result, the examiner issued a rejection of the design application under 35 U.S.C. § 102 as being anticipated by the utility application.

Floyd appealed the rejection to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board ("PTAB" or Board). The PTAB affirmed the examiner's rejection, and Floyd appealed the PTAB's decision to the Federal Circuit. Specifically, Floyd argued that the utility application included sufficient written description to support the design application under 35 U.S.C. § 112. Floyd did not appeal the PTAB's decision upholding the Examiner's rejection based on lack of novelty.

The utility application relates to a cooling blanket featuring "an integrated ventilation system" and "multiple, sealed compartments." The specification recites that "the embodiment can be made in any size suitable for cooling the body core, or entire body of any human or animal," and that "[w]hile [the] description contains many specifications, these should not be construed as limitations on the scope, but rather as an exemplification of several embodiments. Many other variations are possible."

Floyd first argued that the utility application was not limited to the six-by-six and a six-by-four configurations shown in its drawings, but instead disclosed, more broadly, any patterns with rectangular shapes and cross-hatched channels. Floyd pointed to a statement in the written specification that the blanket "can be made in any size for cooling the body core, or entire body, of any human or animal," arguing that the utility application encompassed a variety of potential designs, including the six-by-five configuration claimed in the later-filed design application.

The Board held that the broad language used in the utility

application failed to show possession of the six-by-five

configuration claimed in the design application. The Board

emphasized that Floyd did not disclose or describe the precise

visual appearance of the six-by-five array in the utility

application, since the reference to "any size"

could reasonably be interpreted as indicating that the rectangular

compartments may vary in size while

the number of compartments stays the

same.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the Board's interpretation,

explaining that the broad language in the utility application only

vaguely generalized the presented embodiments without providing an

accurate description of the specific design claimed in the design

application.

Floyd next argued that the six-by-five configuration should be interpreted as an intermediate size between the six-by-four and six-by-six configurations. Noting that the written description of the earlier-filed application need not recite exact claim language in the later-filed application in order for a priority claim to be valid, Floyd asserted that she was in possession of the six-by-five configuration at the time of filing the utility application notwithstanding its absence from that disclosure. Floyd emphasized that due to the predictability of the invention, a skilled artisan would reasonably design the six-by-five configuration based on the six-by-four and six-by-six configurations.

The Board found that the six-by-four and six-by-six configurations were not part of a continuous range but instead, represented two distinct embodiments of the invention. Therefore, the fact that "five" lies numerically between the "four" and "six" should not be considered sufficient to infer the six-by-five configuration from the six-by-six and six-by-four configurations. Furthermore, the Board noted that the two presented embodiments differed not only in the number of compartments, but also in their shape.

The Federal Circuit again agreed that the similarities between the figures in the two applications were insufficient to establish possession of the six-by-five configuration, given that the figures in the utility application do not define a range of variations. The court clarified that "predictability of the technology embodied in the utility application does not necessarily carry over into the predictability of the designs." In that regard, while a numerical range may support intermediate values in an earlier utility patent application, a design claimed in a subsequent design patent application must be explicitly disclosed or depicted in the earlier application to serve as a basis for priority.

Next, the Federal Circuit agreed with the Board that the disclosure of two specific configurations (the six-by-four and six-by-six configurations) did not show evidence that the applicant was in possession of a third, different configuration (six-by-five configuration). In that regard, the generic reference to "a plurality of individualized compartments" in the utility application was insufficient to inherently disclose the six-by-five configuration later claimed in the design application.

In a further argument, Floyd urged that the number of compartments of the blanket described in the utility application was a functional element, dictated by the blanket's intended purpose (e.g., blankets of different sizes may be used by different users), rather than an ornamental element.

The Board found that this argument was forfeited because it had never been raised during prosecution, and the Federal Circuit agreed. Despite this procedural forfeiture, the Board substantively disagreed that the number of compartments of the blanket was a functional element and once again the appellate court agreed, concluding that the number of compartments was not primarily dictated by the blanket's functionality.

As a result, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board's decision, holding that the later-filed design application lacked written description support in the earlier-filed utility application and therefore, could not claim the benefit of the filing date of that utility application. Furthermore, the Federal Circuit held that as a result of the failure of the priority claim, the utility application qualified as prior art under 35 U.S.C. § 102 and anticipated the design application, noting that a description that suffices to anticipate under 35 U.S.C. § 102 does not necessarily satisfy the written description requirement under 35 U.S.C. § 112.

Footnote

1. In Re Floyd, No. 23-2395, 2025 WL 1163561 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 22, 2025).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]