- within Food, Drugs, Healthcare and Life Sciences topic(s)

- in United States

- within Food, Drugs, Healthcare, Life Sciences, Technology and International Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit industries

Executive Summary

This study examines how innovation in patient access to treatment without a prescription could address critical patient needs. Notable disparities in healthcare access and outcomes persist across both geographic areas and socio-economic groups in the US. Some gaps in healthcare service and outcomes may be bridged by extending access to more medicines without the need for a prescription. However, the range of candidate medicines available for switching to OTC status historically has been limited by the ability of patients to interpret product labeling and make appropriate selfselection decisions. Recent regulatory changes allowing companies to leverage new technologies and innovate new ways to aid the patient self-selection process may pave the way to better access to needed medications. While retail pharmacies bridge some of these gaps, non-traditional retail sources for medicines, such as dollar stores, may also play an important role because they are often located where healthcare access challenges are greatest. Broadening the range of treatments available via the OTC pathway is therefore likely to have a beneficial impact in areas otherwise experiencing health care access challenges, particularly if nontraditional outlets are included in the retail mix.

1. Introduction

Inadequate access to healthcare is a significant public health concern. According to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), 76 million Americans (one in five) live in a primary care Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA).1 Some of these shortage areas have earned the nickname "medical deserts" in academic studies; 2 in the US, they are particularly concentrated in rural areas and the South. HRSA forecasts indicate the shortage situation is unlikely to improve in the foreseeable future.

Difficulties booking office visits, long wait times, inadequate insurance coverage, and travel can be obstacles to obtaining needed prescription medications. Innovations in remote physician access, such as telehealth visits, may address some, but not all, of these issues. On the insurance side of the equation, the trend toward high deductible health plans has placed a greater financial burden on patients by increasing out-of-pocket costs for prescription medications—particularly within low-income households.3 Higher patient burdens lead to lower prescription medication utilization and worse medical outcomes.4 These combined trends can make it harder for many Americans to access needed medications via the traditional prescription pathway.

The broad availability of OTC medications at retail locations beyond pharmacies can be crucial—especially in areas that are pharmacy deserts, where the local dollar store could be the only store around.5 Recent regulatory changes have opened the door to innovation in how companies aid patient self-selection decisions.

That innovation will likely further benefit patients by making a broader range of therapies available via this pathway.

I begin this paper by reviewing the trends and geography of healthcare access in the US. The most important trend in healthcare delivery is that the growth in demand for healthcare services through population growth and aging will outpace the growth in supply of physicians. But access issues are also geographical in nature. I show access issues are particularly concentrated in rural areas and in the South. A review of statistics on insurance coverage, savings rates, and rising costs of prescription medication demonstrates financial access may be a significant barrier to adequate healthcare in lower-income groups. My analysis also links HPSA data aggregated to the county level with data on pharmacy and dollar store locations. I demonstrate that in counties with higher rates of health professional shortages for primary care, per-capita pharmacy access is in general not any worse than in counties with better overall healthcare access. Though this statistic does not account for the greater driving distances typical of rural areas, it does indicate retail locations can have a role in alleviating access issues. Because OTC medicines can be obtained in any retail setting, I also link the HPSA data to the locations of a dollar store chain that sells OTC products. I find areas with a high fraction of the population in HPSAs have nearly five times higher per-capita access to that chain's stores than areas with a low fraction of the population in HPSAs. This indicates, via greater OTC access, retail chains (like dollar stores) that cater to rural and lower-income populations may be ideally situated to address some of the healthcare gaps in HPSAs.

These findings suggest broadening the range of medicines that can be obtained without a prescription at retail locations may be particularly helpful for populations located in areas of primary care shortage.

2. Healthcare Access

2.1. Health Professional Shortages

In areas where health professionals are in short supply, access to a variety of healthcare services can be adversely affected, including the prescribing of necessary medications. HPSAs can be designated for either primary, dental, or mental health professionals and are based on the following criteria:

- Geographic: "A shortage of providers for an entire group of people within a defined geographic area."

- Population: "A shortage of providers for a specific group of people within a defined geographic area."

- Facility: Certain medical facilities may be automatically designated as shortage areas, and others may be designated based on a shortage of providers.6

State Primary Care Offices are responsible for submitting applications for the designation of an HPSA. HPSA applications may include data such as clinical practice activity, provider practice locations, and demographic data. States have an incentive to provide these data and apply for HPSA designations because a variety of federal programs, such as the National Health Service Corps (NHSC), rely on these designations to distribute resources. The HRSA is ultimately charged with evaluating and approving or rejecting the applications.7 The overall process of HPSA evaluation and designation has been going through a modernization over the last 10 or so years.8

As noted in the introduction, the HRSA reports 76 million Americans live in a HPSA for primary care, with more than 13,000 additional practitioners needed to resolve these shortages.9 However, health access issues in the US are not limited to primary care. HRSA also reports 60 million Americans reside in HPSAs for dental health, and more than 10,000 practitioners would be needed to resolve those shortfalls.10 Similarly, HRSA reports 122 million people reside in HPSAs for mental health, and over 6,000 additional practitioners would be needed resolve those shortfalls.11

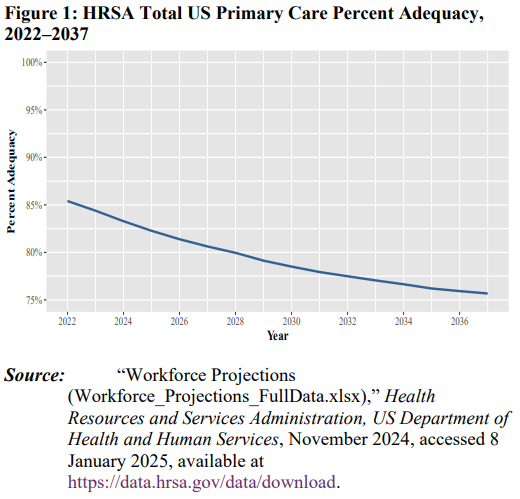

These shortages appear unlikely to improve. As depicted in Figure 1, the national average supply of primary care physicians relative to demand was approximately 85% in 2022 and is projected to fall through 2037.

2.2. Demand for and Supply of Physicians

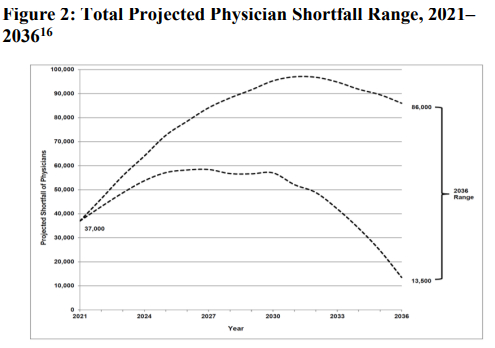

Shortages in any market are generally the result of an excess in demand relative to available supply. Here, physician shortages refer to an excess of demand for healthcare services relative to the available supply of physicians. Among the consequences of a shortfall in physicians is a potential shortfall in available prescribers. A 2024 report published by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) states: "We continue to project physician demand will grow faster than supply under most of the scenarios modeled...."12 Largely corroborating the HRSA forecasts, the AAMC projects a worsening of physician shortages through 2030. The AAMC, however, projects possible improvements after 2030 (as shown in Figure 2). In particular, this report projects that by 2036 there will be:

- A shortage of between 20,200 and 40,400 primary care physicians;13

- A shortage across non-primary care specialties of up to 46,200 physicians; 14 and

- A total shortfall between 13,500 and 86,000 physicians.15

Demand growth is a key contributor to expected shortages, driven primarily by the growth and overall aging of the US population. The AAMC report projects a population growth of 8.4% between 2021 and 2036. In this same time period, the 65-and-older population is projected to increase by 34.1%, and the 75-and-older population is expected to increase by 54.7%. The older the population, the more medical care required, increasing physician demand.17

Several factors contribute to projected physician supply shortfalls in the US. One of these is supply bottlenecks in graduate medical education (GME) positions.18 Each year, over 4,000 doctors graduate from medical school but are unable to obtain GME positions to become licensed physicians.19 Most of these medical residencies are funded by the federal government. In 2018, 86% of medical residencies were funded by Medicare, Medicaid, and the VA; 2% were funded by hospitals and philanthropists; and the remainder of funding came from state matching of Medicaid funds.20 As of 2020, Medicare funded approximately $10 billion of the $ billion total funding for GMEs. owever, Medicare's ability to fund GME positions is limited; the 1997 Balanced Budget Act set a cap on the number of GME positions that can receive direct funding from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.21 While the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 allows for 1,000 additional GME positions above this cap (phased in over several years), this is not sufficient to give all doctors graduating from medical school GME positions.22 Indeed, The New York Times reports there are as many as 10,000 doctors who have graduated from medical school and consistently apply to GME programs but are rejected and, as a result, are unable to become practicing physicians, despite demand for their labor.23

Notably, the AAMC's shortage pro ections assume investments in GME continue to grow as the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 funds an additional 200 GME positions each year between 2023 and 2027. In addition, states and hospitals have recently begun funding additional GME positions. The AAMC report notes that if GME investments do not continue to grow, then "the pro ected shortfalls would be much more severe" and would "closely resembl[e] those presented in the 2021 report, which projected a shortfall of up to , physicians by ."24

Another factor negatively affecting the supply of physicians is the rate at which physicians exit the profession. The overall aging of the population has supply-side impacts as well, with it being "very likely that more than a third of currently active physicians will retire within the next decade."25 Another source of physician exit is burnout, which has been estimated at more than 50% over the past 20 years.26 A substantial and persistent problem in the physician workforce, burnout is more common among younger physicians and high-performing physicians. Younger physicians experiencing burnout may leave the healthcare workforce altogether, opting for alternative careers with lower stress levels. The effects of this are longer-lasting than early retirement—the healthcare workforce loses many years of potential service from these young workers, as opposed to the loss of just a few years from older workers retiring. Moreover, as high-performing employees leave, the overall quality of care deteriorates.27 Among physicians experiencing burnout who continue practicing, overall medical care worsens, and the risk of medical errors increases. 28

Common reasons for burnout include too much bureaucracy, large amounts of time spent using electronic systems, and long working hours.29 Unsurprisingly, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated issues related to burnout. A 2022 paper compared results of a survey given to physicians in 2020 and 2021 and found several metrics of burnout had increased substantially. In particular, mean emotional exhaustion scores increased by 38.6%; mean depersonalization scores increased by 60.7%; and, while only 38.2% of physicians had one or more manifestations of burnout in 2020, 62.8% did in 2021.30

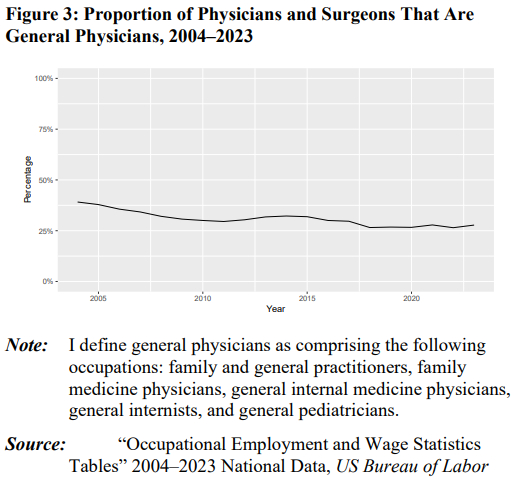

Shortfalls in the supply of primary care physicians also fit into a long-developing shift from physicians practicing primary care to focusing on specialties, largely beginning after World War II. As of 2023, only 28% of practicing physicians in the US were in general internal medicine, family medicine, or pediatrics. This is much lower than the proportion of general practitioners in other western nations.31 Indeed, data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that even in the past two decades, the proportion of physicians and surgeons that are generalists has declined substantially, from almost 40% in 2004 to less than 28% in 2023. See Figure 3.

This shift from general care to specialization is often theorized to be due to the higher salaries specialization offers—especially amid the increasingly large amounts of debt doctors take out in medical school. This shift may also represent a belief that specialties offer preferable lifestyles.32 It should be noted, however, that while the share of physicians pursuing careers in primary care has declined, the number of primary care physicians per capita has remained relatively stable.33 This, however, does not address the aging of the US population and the growing healthcare demand stemming from that trend.

Footnotes

1 "Health Workforce Shortage Areas," Health Resources & Services Administration, US Department of Health & Human Services, accessed 10 January 2025, available at https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas. ("Health Workforce Shortage Areas").

2 Brînzac, Monica, et al., "Defining Medical Deserts—An International Consensus Building Exercise," European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 33, No. 5, 2023, p. 785–788.

3 Abdus, Salam, "Financial Burdens of Out-of-Pocket Prescription Drug Expenditures Under High-Deductible Health Plans," Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 36, No. 9, 2020, p. 2903–05.

4 Shrank, William, et al., "The Epidemiology of Prescriptions Abandoned at the Pharmacy," Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol 153, No. 10, 2010, p. 633–640.

5 "Featuring a wide variety of dollar general OTC products, we make it easy and affordable to maintain your health without a prescription." See "Medicine Cabinet," Dollar General, accessed 14 February 2025, available at https://www.dollargeneral.com/c/health/medicine-cabinet.

6 "What Is Shortage Designation?" Health Resources & Services Administration, US Department of Health & Human Services, June 2023, accessed 25 June 2024, available at https://bhw.hrsa.gov/workforce-shortage-areas/shortage-designation#hpsas.

7 "Reviewing Shortage Designation Applications," Health Resources & Services Administration, US Department of Health & Human Services, August 2022, accessed 25 June 2024, available at https://bhw.hrsa.gov/workforce-shortage-areas/shortagedesignation/reviewing-applications.

8 "Understanding the Shortage Designation Modernization Project," Health Resources & Services Administration, US Department of Health & Human Services, August 2022, accessed 25 June 2024, available at https://bhw.hrsa.gov/workforce-shortageareas/shortage-designation/modernization-project.

9 "Health Workforce Shortage Areas."

10 Id.

11 Id.

12 "The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2021 to 2036," Association of American Medical Colleges, March 2024, accessed 25 June 2024, p. 55, available at https://www.aamc.org/media/75236/download?attachment. (AAMC Report).

13 Ibid.

14 Id, p. 3–4, Exhibits 6, 8, 10, and 12. The projected shortage of non-primary care specialties comprises the sum of shortages for medical specialist physicians, surgeons, primary-care-trained hospitalists, and other specialist physicians.

15 Id, p. 55.

16 Id, Exhibit ES-1.

17 Id, p. 32–34.

18 A GME position is required for all graduates to become physicians.

19 Ahmed, Harris and J. Carmody, "On the Looming Physician Shortage and Strategic Expansion of Graduate Medical Education," Cureus, Vol. 12, No. 7, 2020.

20 See, e.g., Martinez, Ramon, "State-Supported Physician Residency Programs," MOST Policy Initiative, accessed 15 November 2024, available at https://mostpolicyinitiative.org/science-note/state-supported-physician-residencyprograms/. Medicare has been funding graduate medical education since the 1960s, but this funding was initially intended to be temporary. Medicare funding covers direct expenses (e.g., salaries and admin costs) and indirect expenses (additional costs of patient care that come from having a GME program). Direct funding is determined based on a set formula with three variables: (1) weighted resident count, (2) a per-resident dollar amount specific to the hospital, and (3) proportion of the hospitals inpatient days that were from Medicare patients. Indirect funding is mostly given on a per-Medicare patient discharge basis (see, e.g., "GME Financing," Graduate Medical Education that Meets the Nation's Health Needs, ed. Jill Eden, Donald Berwick, and Gail Wilensky, National Academies Press, 2014.).

21 Ahmed, Harris and J. Carmody, 2020.

22 "Frequently Asked Questions on Section 126 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), 2021," Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, accessed 9 July 2024, available at https://www.cms.gov/files/document/frequently-asked-questions-section126.pdf.

23 Goldberg, Emma, "'I Am Worth It:' Why Thousands of Doctors in America Can't Get a Job," The New York Times, 19 February 2021, updated 20 July 2021, accessed 9 July 2024, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/19/health/medical-school-residencydoctors.html.

24 Specifically, the difference between projections with no growth and 1% annual growth (beyond the growth resulting from the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021) is a supply of 41,000 physicians by 2036. See AAMC Report, p. vi, 3.

25 Id, p. viii.

26 Bhardwaj, Anish, "COVID-19 Pandemic and Physician Burnout: Ramifications for Healthcare Workforce in the United States," Journal of Healthcare Leadership, Vol. 14, 2022, p. 91–97.

27 Ibid.

28 Yates, Scott, "Physician Stress and Burnout," The American Journal of Medicine, Vol. 133, No. 2, 2020, p. 160–164.

29 Ibid.

30 Shanafelt, Tait, et al., "Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction with Work-Life Integration in Physicians During the First 2 Years of the COVID-19 Pandemic," Mayo Clinical Proceedings, Vol. 97, No. 12, 2022, p. 2248–2258.

31 Dalen, James, et al., "Where Have the Generalists Gone? They Became Specialists, then Subspecialists," The American Journal of Medicine, Vol. 130, No. 7, 2017, p. 766– 768.

32 Dalen, et al., 2017.

33 "Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics Tables" 2004–2023 National Data, US Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed 31 July 2024, available at https://www.bls.gov/oes/tables.htm; "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, District of Columbia and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2024 (NST-EST2024-POP)," US Census Bureau, Population Division, December 2024, accessed 28 January 2025, available at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/timeseries/demo/popest/2020s-national-total.html; "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019 (NST-EST2019-01)," US Census Bureau, Population Division, December 2019, accessed 11 February 2025; and "Intercensal Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex and Age for the United States: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2010 (US-EST00INT-01)," US Census Bureau, Population Division, September 2011, accessed 11 February 2025, available at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/intercensal2000-2010-national.html.

To view the full article click here

Originally published by GW Competition & Innovation Lab

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.