- within Antitrust/Competition Law, Technology and International Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit industries

Article by Christian Dippon1

Introduction

On 9 September 2008, US Senator Herb Kohl (D-WI), chairman of the Senate Antitrust Subcommittee, sent a letter to the CEOs of Verizon Wireless, AT&T Mobility, Sprint Nextel, and T-Mobile (the four largest US mobile carriers) demanding an explanation for recent price increases for text messaging. Text messaging is a rather broad term that means sending messages from one device to another using a wireless technology and includes services such as short message service (often called SMS), email, instant messaging, Internet access, voice SMS (where the text is converted to voice), text-to-landline SMS (where the text is also converted to voice), and the sending of content (e.g., pictures or video messaging). Senator Kohl appears to be questioning only the prices of SMS, which is just one form of text messaging. This distinction is crucial as there is a significant difference in the use of SMS and other forms of messaging such as emails, Internet access, and voice SMS. Senator Kohl's letter asks the carriers to "justify" what "some industry experts contend ..." are price increases that "do not appear to be justified by any increases in the costs associated with text messaging services." Specifically, Senator Kohl asks for:

- An explanation of why text messaging rates have dramatically increased in recent years.

- Cost, technical, or other factors "that justify a 100% increase in the cost of text messaging from 2005 to 2008.

- Data on the utilization of text messaging during this time period.

- Comparison of prices charged today as opposed to 2005 for text

messaging as compared to other services offered by the operators,

such as:

- Prices for voice calling

- Prices for sending emails

- Prices for data services such as Internet access over wireless devices

- Information on whether the pricing structure for text messaging

differs in any significant respect from the pricing of their

competitors

Only days after Senator Kohl's letter was released, consumer class action lawsuits began to be filed in various jurisdictions. For instance, a class action complaint was filed in the US District Court, Northern District of Ohio, Western Division ("Ohio suit") alleging an "illegal scheme of price-fixing conspiracy ...." A similar suit was also filed in the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division. As of the writing of this paper, there have been 20 related consumer class action lawsuits filed.

The Allegations Must Be Put Into Economic Context

Senator Kohl's initial letter, as well as the various suits filed since, illustrates a fundamental misunderstanding of economics and market forces in particular. Unfortunately, as we have recently seen with the consumer class action lawsuits targeting early termination fees, sound economic arguments are frequently ignored by government bodies and the courts in lieu of politics and supposed "consumer protection." In the following, I address only a few of the economic considerations that must be taken into account when reviewing the allegations raised by Senator Kohl and the various lawsuits that were filed after his letter.

First, prior to studying any allegations of market power or price fixing, Senator Kohl and the plaintiffs in the consumer class action suits must specify the product and geographic markets in which the alleged price fixing or unjustified price increases took place. Any competitive analysis must be conducted within the context of a market. Competition occurs within a market; prices are formed by supply and demand conditions within a market; and, the public interest can only be evaluated when viewed as the welfare of consumers within a market.

In popular parlance, the term "market" often has different connotations. Some describe it as a physical location where goods or services are bought and sold, while others see it as a loose aggregation of transactions for a good or service with no reference to where those transactions happen. The economic definition of a market combines both product (or service) and geographic characteristics. Two products are in the same market if sufficient substitutability can be established between them. For instance, as explained above, SMS is only a subset of text messaging. A text messaging alternative includes email. While formal tests likely will find that email services are economic substitutes to SMS, email service is frequently considered in the same economic market as SMS. Furthermore, today's telecommunications competition takes place for a customer's entire wireless bundle and often for the customer's entire communications portfolio, including video, voice, data (triple play), or video, mobile voice, wireline voice, and data (quadruple play). In other words, it is unlikely that the market definition will reveal that SMS, or some other subset of text messaging, constitutes its own economic market. If SMS is part of the larger text messaging market, one must assess SMS price changes taking into account the other services in that market, just as a price increase for milk at the supermarket says nothing about market power for the store.

Even if SMS constitutes a separate market, Senator Kohl's concern and the plaintiffs' allegations can only be justified if it can be shown that the four mobile operators have market power in this properly defined market and have abused this power, or that they have colluded. The first consideration (of having market power) is likely incorrect, as the US Federal Communication Commission (FCC)'s analyses have repeatedly found the US mobile market to be "effectively competitive."2 As for the second consideration, the parties would need to demonstrate that the defending operators have colluded in setting the price for SMS (and nothing else), or that they collude on all products and services in the relevant market. It is quite unlikely that either of these scenarios is supported by economic theory and the facts. Colluding on SMS only and competing on all other products and services in a market makes little economic sense, and collusion on all products and services is not supported by market facts and the FCC's annual competition reports.

Second, it is interesting to observe how Senator Kohl's allegations of a "decrease in competition and an increase in market power" have been translated by the plaintiffs in the consumer class action lawsuits as "price fixing." Albeit related, these are rather different economic concepts. Price fixing is a form of collusion where market players agree to sell the same product or service at the same price. The objective of such an action is for market participants to escape market forces and set their own prices. The economic literature explains in detail the market structures and incentives that must be in place for collusion to exist, persist, and be beneficial for its participants. Influencing factors include the incentive to coordinate (oligopolistic market structure, similar market shares, comparable costs, analogous capacity constraints, and related ownership structures), as well as the ability to coordinate (i.e., ability to detect cheating, the enforceability of compliance, and actual and potential market constraints). In contrast to plaintiffs' class action allegations, Senator Kohl's "concern" appears to be much broader as he focuses on a "decrease in competition," and an "increase in market power." Market power is generally defined as the ability to raise prices by restricting output without incurring a significant loss of sales or revenues. Senator Kohl seems to correlate the alleged increase in market power with an alleged decrease in competition due to market consolidations. The class action plaintiffs, however, seem to argue that the increase in market power and the decrease in competition are the result of collusion. Hence, although the class action matters seem to be the result of Senator Kohl's investigation, the two parties appears to base their cases on different economic theories.

Senator Kohl is alluding to the consolidations that have characterized the telecommunications sector in recent years, most recently the merger of Verizon Wireless and Alltel, as the source of the decrease in competition. While the FCC still has to vote on the Verizon-Alltel merger, the Commission has previously taken the position that:

Consolidation and exit of service providers, whether through secondary market transactions or bankruptcy, may affect the structure of the mobile telecommunications market. A reduction in the number of competing service providers due to consolidation or exit may increase the market power of any given service provider, which in turn could lead to higher prices, fewer services, and/or less innovation. However, consolidation does not always result in a negative impact on consumers. Consolidation in the mobile telecommunications market may enable providers to achieve certain economies of scale and increased efficiencies compared to smaller operators. If the cost savings generated by consolidation give the newly enlarged provider the ability and the incentive to compete more aggressively, consolidation could result in lower prices and new and innovative services for consumers. Moreover, it is unlikely that competitive harm will result from consolidation among service providers licensed to operate in separate geographic markets.3

These and other economic considerations must be taken into account when reviewing Senator Kohl's concerns and the class action plaintiffs' allegations. Only when the economic markets have been defined and the economic theory of this matter (whatever it might be—price fixing or some other form of market power) have been established can the allegations be properly addressed.

Market Evidence Does Not Support The Allegations

The allegation made in Senator Kohl's letter seems to be at the heart of the plaintiffs' class action lawsuits:

[T]he cost for a consumer to send or receive a text message has increased by 100%. Text messages were commonly priced at 10 cents per message sent or received in 2005. Currently the rate per text message has increased to 20 cents on all four Defendant wireless carriers. Defendant Sprint was the first carrier to increase the text message rate to 20 cents per message, and now all of its three main competitors have matched this price increase.4

In evaluating these allegations, it is important to note that the rates the plaintiffs refer to are metered, nonbundled rates. That is, these rates only apply to subscribers that do not have a plan or a plan add-on that includes discounted messaging rates. Thus, I refer to the rates in question as "default rates" or "pay-as-you-go rates." These default rates compare to the long distance per-minute charges that apply to consumers who do not sign up with a particular long distance carrier or who do not sign up for a particular long distance calling plan. For instance, AT&T's default rate for an international wireline phone call to Switzerland is $1.49 per minute. However, by subscribing to AT&T's Worldwide Value Calling plan for a monthly recurring charge of $5.00, the same rate drops to $0.09 per minute—a discount of 94 percent.

Furthermore, the current evidence does not seem to support the allegations, as not all mobile operators in the US charge the same price for pay-as-you-go texting. Specifically, per the operators' websites, Verizon Wireless, AT&T Mobility, and Sprint Nextel all charge $0.20 per text message received and sent. Furthermore, as of 29 August 2008, T-Mobile also charges $0.20 per text message. This price increase came into effect five months after AT&T Mobility increased its default SMS rate. However, Alltel charges either $0.10 or $0.15, depending on plan, while Virgin Mobile charges $0.10. It is also worthwhile noting that Alltel and Virgin Mobile have different rates ($0.25) for picture messaging, while other carriers do not make this distinction.

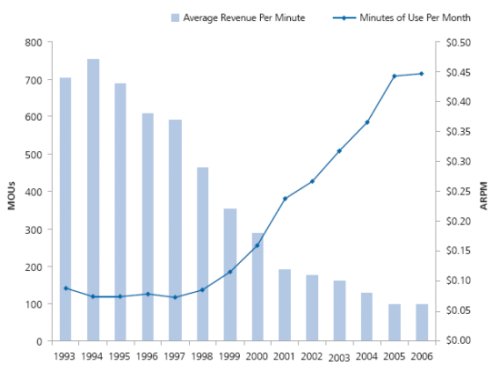

While this basic SMS rate comparison indicates different pricing strategies for default SMS prices for at least some of the carriers, it is important to note that the service bundles that include text messaging offered by these carriers are all priced differently. This is discussed in detail below. Moreover, counter to the allegations, wireless prices have been decreasing steadily since approximately 1994, leading to a strong uptake in wireless usage. Specifically, FCC data on national wireless trends show a dramatic increase in wireless usage associated with an equally dramatic decrease in prices (as measured by the average price per minute) of wireless usage. As illustrated in Figure 1 below, from 1993 through 2006, wireless mobile usage (minutes-of-use per subscriber per month) grew by 400 percent to over 700 minutes per mobile subscriber per month, and the average charge per wireless voice minute fell by 86 percent to only $0.06 per minute.

Figure 1. Trends In US Wireless Usage And Voice Charges

Per Minute

1993–20065

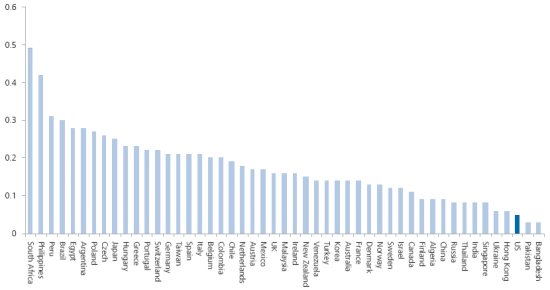

US prices for all wireless services are also among the lowest in the world, further undermining the claims that US wireless carriers charge supracompetitive prices. To arrive at this conclusion, I benchmarked the average voice revenue-per-minute (RPM) against 49 other countries for which 2006 RPM data were available.6 As shown in the figure below, as of year end 2006, the US PPI-adjusted RPM was lower than in 46 other countries and higher than in two countries (Pakistan and Bangladesh). It is also lower than the average (on both a weighted and unweighted basis).

Figure 2. PPI-Adjusted RPM Of Outgoing And Incoming

Voice Traffic

2006

Source: Derived from Merrill Lynch, Global Wireless Matrix 4Q06.

Hence, considered in the appropriate economic context, the market evidence seems to support neither Senator Kohl's concerns nor the allegations raised in the class action lawsuits.

Price Increases Are Not Necessarily Anticompetitive

Senator Kohl demands an explanation of why text messaging rates have dramatically increased in recent years. Assuming that the alleged price increases are accurate, there are many reasons beyond increased costs why prices could have increased. One obvious explanation for a price increase could be as simple as pricing strategy. Specifically, it has long been recognized that mobile operators compete in terms of bundles. As reported by the FCC:

To encourage subscribers to purchase monthly data packages, providers offer various types of discounts on monthly data packages as compared to pay-as-you-go data usage. For example, customers may be able to avoid incurring kilobyte-based or airtime charges for downloading and using certain applications by subscribing to a monthly data package. In addition, the unit price of sending text messages (or "SMS") and multimedia messages with the purchase of monthly messaging packages is lower than the flat pay-as-you-go rate for such messaging services. Another discount method is to offer a reduced flat rate per application to subscribers who purchase a monthly data package. As noted in the Eleventh Report, Telephia Inc. ("Telephia") found that subscribers' propensity to purchase monthly data packages, as opposed to using mobile data applications on a pay-as-you-go basis, varies by type of application.

For example, Telephia estimated that subscribers who access the Web via their cellphones are nearly twice as likely to subscribe to monthly data packages as to use a pay-per-use option. According to Telephia, this is because consumers perceive mobile web browsing to be too expensive without using monthly data packages, and want to avoid being surprised by additional charges billed to their monthly cellphone invoices. Similarly, Telephia estimated that MMS users are nearly three times as likely to subscribe to monthly MMS packages as to use the pay-per-use option. Among SMS users, however, Telephia found that the pay-per-use option and monthly SMS packages were almost equally popular.7

Hence, the alleged price increases for SMS might be a part of the operators' pricing strategies to move subscribers from pay-as-you-go to service bundles, including possibly unlimited usage of certain services (such as SMS). Typically there is nothing anticompetitive about such a strategy, as carriers simply respond to their customers' needs. For instance, customers that do not select a text messaging bundle send a signal that they do not use the service sufficiently to warrant a monthly recurring expense. For these customers, the price for texting might not be an important attribute in their purchase decision. Alternatively, subscribers that purchase a text messaging bundle signal that they anticipate using the service and hence select a plan with more a favorable (to them) text messaging price.

Text Messaging Prices Among US Operators Vary

Plaintiffs argue that the defendants in their cases "have engaged in a contract, conspiracy, trust or combination designed to raise the prices at which they sold Texting to artificially inflated levels."8 In his letter, Senator Kohl points out that, by the end of September, prices will have increased to $0.20 "on all four wireless carriers." The market facts do not seem to support these allegations because the wireless operators' messaging prices vary significantly for subscribers that plan to use this service. Consider, for instance, Verizon Wireless. Verizon Wireless offers a basic, individual wireless calling plan with 450 monthly anytime minutes for $39.99 per month. Subscribers to this plan are charged $0.20 for each text message received and $0.20 for each text message sent.9 The company also offers a plan for $59.99 that is almost identical (same monthly minutes allowance, same overage, and same basic calling plan features) with one noted exception—it includes unlimited text, picture, video, and instant messaging. Thus, at $0.20 for each text message sent, a subscriber that sends more than 100 text messages per month (text, picture, or video) is better off with the second plan. In fact, since incoming text messages also incur a charge and subscribers who send text messages typically receive text messages in return, this threshold is likely even lower. According to the CTIA, there were 262.7 million wireless subscribers and 75 billion monthly SMS messages sent in the US as of June 2008.10 This averages to 285 text messages per month per subscriber—far exceeding the threshold for the $59.99 plan. It follows that an average subscriber who (correctly) selects the $59.99 plan effectively pays $0.07 per text message (sent or received).

AT&T Mobility also offers a $39.99 plan with 450 monthly airtime minutes. However, this plan differs from Verizon Wireless' plan. For instance, for an additional $5.00 per month, 200 text, video, or picture messages are included, resulting in a per-message price as low as $0.025. Larger text messaging packages can also be added. As an example, for $20.00 per month, a subscriber can get unlimited messaging. At an average of 285 messages per month, the typical subscriber is better off with AT&T's "Messaging 1500," which is priced at $15.00 and includes 1,500 messages. This would result in an effective rate of $0.05 per text message (sent or received). T-Mobile charges $0.20 per text message for plans that do not include a text messaging bundle and $10.00 per month for unlimited messaging. Thus, an average subscriber pays $0.035 per text message under T-Mobile's plan.11

Sprint Nextel's pay-as-you-go rate for messaging is $0.20 and the company offers a wide array of mobile communications bundles. For example, the "Talk" plan offers 450 minutes for $39.99 per month. For an additional $10.00, subscribers can purchase the "Talk/Message/Direct Connect" plan, which includes (among other things) "unlimited nationwide, text, picture and video messaging to anyone on any network."12 This plan translates to $0.035 per text message for the average subscriber.

Finally, Alltel's pay-as-you-go rate for text messaging is either $0.10 or $0.15 per text message sent or received and $0.25 per video message sent or received. Alltel's messaging bundles are also quite different from its competitors. For instance, for an additional $7.99 per month, subscribers get 400 text, video, or picture messages per month plus unlimited messaging to their calling circle. Under this plan, an average subscriber pays $0.028 per text message.

The table below summarizes the rates and illustrates that text messaging rates as currently offered by US mobile operators are quite different. I note that there are many other differences in the overall bundles offered by operators. This result alone casts serious doubts on Senator Kohl's concerns and the plaintiffs' allegations.

Table 1. Comparative Messaging Rates

US Mobile Operators

|

Verizon Wireless |

AT&T Mobility |

T-Mobile |

Sprint |

Alltel |

|

|

Default rate per message – text |

$0.20 |

$0.20 |

$0.20 |

$0.20 |

$0.10 or $0.15 |

|

Default rate per message – video |

$0.20 |

$0.20 |

$0.20 |

$0.20 |

$0.10 or $0.15 |

|

Default rate per message – picture |

$0.20 |

$0.20 |

$0. |

$0.20 |

$0.10 or $0.15 |

|

Monthly bundle rate for > 285 messages |

$20.00 |

$15.00 |

$10.00 |

10.00 |

$7.99 |

|

Monthly bundle rate for unlimited messages |

$20.00 |

$20.00 |

$10.00 |

$10.00 |

$12.99* |

|

Bundle rate per message for average user |

$0.07 |

$0.05 |

$0.04 |

$0.04 |

$0.03 |

* Unlimited messaging only applies to circle.

Source: Company websites, NERA research

US Rates For Text Messages Compare To Other Countries

In order to review Senator Kohl's concerns and to address the plaintiffs' allegations, it is informative to compare the text messaging rates currently charged in the US to the rates charged in other countries. Such a comparison, however, is not straightforward as the demand for text messaging services and the regulatory, political, and technical environments differ significantly across countries. For instance, in some countries carriers do not charge for text messages received. A comparison, however, is still valuable as it sheds light on two important aspects of this matter. First, as shown in the table below, the price charged by US carriers for a text message sent to a domestic address does not differ significantly from the prices charged in other countries. Specifically, the non-weighted average price of a domestic SMS sent in the non-US countries in the table below is $0.20. In contrast, US carriers charge a non-weighted average of $0.19. Hence, based on this sample evidence, it appears that US carriers are charging rates that are generally in line with international benchmarks.

Second, and more important, is the fact that it is not uncommon for several, if not all, mobile carriers in a country to charge the same default SMS sent rate. Mobile carriers in Canada all charge identical rates. The same is true for Germany and Australia. In the United Kingdom, three of the four carriers charge the same SMS rate, while in Switzerland and Austria two carriers charge identical rates.

While the comparison below is admittedly not a comprehensive international comparison, it does support the fact that competitive market environments do not necessarily result in different prices. In fact, as prices in competitive markets tend towards incremental costs, one would expect prices to be the same or at least similar.

Table 2. International Comparison

Pay-As-You-Go Rate Per Domestic SMS Sent

|

Country |

Carrier |

Rate (US$) |

|

Australia |

Telstra |

$0.17 |

|

Australia |

Optus |

$0.17 |

|

Australia |

Vodafone |

$0.17 |

|

Australia |

Hutchison |

$0.17 |

|

|

|

|

|

Austria |

T-Mobile |

$0.27 |

|

Austria |

Orange |

$0.34 |

|

Austria |

Hutchison |

$0.13 |

|

|

|

|

|

Canada |

Bell Mobility |

$0.13 |

|

Canada |

Rogers Communications |

$0.13 |

|

|

|

|

|

Germany |

Vodafone |

$0.27 |

|

Germany |

E-Plus Mobilfunk |

$0.27 |

|

Germany |

Debitel |

$0.27 |

|

Germany |

O2 |

$0.27 |

|

|

|

|

|

Switzerland |

Sunrise |

$0.09 |

|

Switzerland |

Orange |

$0.09 |

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom |

Hutchison |

$0.21 |

|

United Kingdom |

T-Mobile |

$0.17 |

|

United Kingdom |

Orange |

$0.17 |

|

|

|

|

|

US |

AT&T Mobility |

$0.20 |

|

US |

T-Mobile |

$0.20 |

|

US |

Sprint Nextel |

$0.20 |

|

US |

Alltel |

$0.15 |

Source: Company websites, NERA research

Cost Data For Text Messaging Is Likely Not Relevant

Senator Kohl's letter to Verizon Wireless, AT&T Mobility, Sprint Nextel, and T-Mobile also asks for cost, technical, or other factors "that justify a 100% increase in the cost of text messaging from 2005 to 2008." As pointed out above, cost increases, or cost data in general, are generally not relevant in competitive markets. Carriers are price takers and thus set their prices based on demand and supply conditions, not individual cost structures.

Furthermore, the cost of providing text messaging likely cannot be determined as most costs of providing wireless services are joint, fixed, and common costs. Consider, for instance, customer acquisition costs—a significant cost factor for mobile carriers. Customer acquisition costs include the costs a carrier incurs to acquire a customer—a customer who will not only purchase text messaging from the operator, but also voice and possibly other services. Similarly, network costs cannot be easily attributed to texting as a stand-alone service. In competitive markets characterized by fixed and common costs, prices are determined by both overall cost and demand factors. The phenomenal growth in demand for texting represents an outward shift in the demand curve that would—all else equal— cause texting prices to rise.

Other Data Requests Are Likely Not Relevant

Senator Kohl also asks the carriers to provide data on the utilization of text messaging during this time period. Doing this correctly would likely require the carriers to ascertain how many SMS messages were sent and received by subscribers with and without a bundle price. With subscribers changing text messaging options frequently, deriving these data will likely be difficult. Furthermore, the data would likely have to be analyzed on a monthly basis. That is, under most plans, there is a difference between a subscriber that receives 300 SMS messages over the course of a year and a subscriber that receives 300 SMS messages in one month and none thereafter. Finally, a comparison of prices charged for text messaging as compared to other services offered by the operators would not be a useful exercise (and likely not feasible), as most services are offered as part of a bundle and thus cannot be broken out in an economically meaningful fashion.

Conclusion

Senator Kohl's investigation of US texting prices has apparently inspired over 20 different consumer class action lawsuits. Unfortunately, none of these lawsuits makes any specific allegations in an economically meaningful context. No market definitions are given, and no evidence of collusion or price fixing is provided. Instead, they rely on Senator Kohl's concerns, which point to "some industry experts" who view the alleged price increases as a sign of a decrease in competition or an increase in market power. Without any definition of what economic market he is referring to, these claims are not complete. The fact remains that, to the best of my knowledge, neither the economic literature nor the FCC's investigations have ever identified pay-as-you-go text messaging as an economic market. Rather, markets have been defined more broadly and they typically include all mobile services (voice and data services). Many industry experts find that the economic market is even broader, encompassing all communication needs, ranging from wireline and wireless voice to data and video. Thus, for Senator Kohl's concerns to be justified, someone must demonstrate that there is collusion in the properly defined economic market that includes pay-as-you-go texting, or it must be demonstrated that carriers somehow collude on one aspect of a service bundle while competing on all other bundle attributes. Neither scenario seems realistic.

In addition to these economic considerations, the market facts also do not support Senator Kohl's case against the mobile industry. US mobile carriers compete on all bundle attributes, including text messaging. Furthermore, when compared to international standards, US rates compare favorably. Making the situation even worse, the data requested from the carriers by Senator Kohl will not shed light on this situation. Rather, Senator Kohl's letter has likely caused the mobile operators to incur significant and unnecessary costs, which in turn might lead to an increase in consumer prices—the exact opposite of what Senator Kohl seems to want to achieve.

Footnotes

1. Christian Dippon is a telecommunications economist and Vice President at NERA Economic Consulting, Inc., an international economic consulting firm. With over 12 years of experience, Mr. Dippon is an expert in telecommunications specializing in wireline, wireless, cable, and emerging technologies. Mr. Dippon has extensive testimonial experience, including depositions, expert testimonies before state court, the Federal Communications Commission, the International Trade Commission, numerous state commissions, and an antitrust authority. Mr. Dippon has consulted to clients in the US, Canada, Japan, the UK, China, Brazil, Singapore, Hong Kong, Spain, Israel, Dominican Republic, Korea, Indonesia, and Australia. Mr. Dippon serves on the Board of Directors of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS) and the International Intellectual Property Institute (IIPI) and is a member of the American Economic Association and the Federal Communications Bar Association. He has authored several telecommunications books and book chapters. His works have been cited by national and international newspapers and magazines, including the Financial Times, BusinessWeek, Forbes, the Chicago Tribune, and the Sydney Morning Herald.

Mr. Dippon can be reached at +1 415 291 1044 or at christian.dippon@nera.com. For more information on telecommunications matters, please visit www.nera.com or www.telecomeconomics.com.

Mr. Dippon has formed his opinion based on publicly available data and information. He reserves the right to amend his opinions and conclusions should further information or data become available.

2. See Federal Communications Commission, Annual Report and Analysis of Competitive Market Conditions with Respect to Commercial Mobile Services, Twelfth Report, WT Docket No. 07-71, adopted 28 January 2008, p. 105 (Twelfth Report).

3. Twelfth Report, pp. 31–32.

4. United States District Court, Northern District of Ohio, Western Division, Class Action Complaint, Jury Trial Demanded, Susan Orians et al. vs. AT&T Inc., Sprint Nextel Corp., T-Mobile USA, Inc., Verizon Communications, Alltel Corporation, p. 8.

5. See Implementation of Section 6002(b) of the Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1993, Annual Report and Analysis of Competitive Market Conditions with Respect to Commercial Mobile Services, Twelfth Report, WT Docket No. 07-71, FCC 08-28, rel. 4 February 2008, Table 14 (Twelfth CMRS Report).

6. The RPM is calculated by dividing monthly voice-only ARPU by monthly minutes of use (MOU).

7. Twelfth Report, pp. 59–60

8. United States District Court, Northern District of Ohio, Western Division, Class Action Complaint, Jury Trial Demanded, Susan Orians et al. vs. AT&T Inc., Sprint Nextel Corp., T-Mobile USA, Inc., Verizon Communications, Alltel Corporation, p. 9.

9. See Verizon Wireless, http://www.verizonwireless.com/b2c/store/controller?item=planFirst&action=viewPlanList&sortOption=priceSort&typeId=1&subTypeId==19&catId=32.

10. See CTIA, "Wireless Quick Facts Mid Year Figures," http://www.ctia.org/media/industry_info/index.cfm/AID/10323.

11. See T-Mobile, http://www.t-mobile.com/shop/plans/cell-phone-plans-detail.aspx?tp=tb2&rateplan=.

About NERA

NERA Economic Consulting ( www.nera.com) is an international firm of economists who understand how markets work. We provide economic analysis and advice to corporations, governments, law firms, regulatory agencies, trade associations, and international agencies. Our global team of more than 600 professionals operates in over 20 offices across North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific.

NERA provides practical economic advice related to highly complex business and legal issues arising from competition, regulation, public policy, strategy, finance, and litigation. Founded in 1961 as National Economic Research Associates, our more than 45 years of experience creating strategies, studies, reports, expert testimony, and policy recommendations reflects our specialization in industrial and financial economics. Because of our commitment to deliver unbiased findings, we are widely recognized for our independence. Our clients come to us expecting integrity and the unvarnished truth.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.