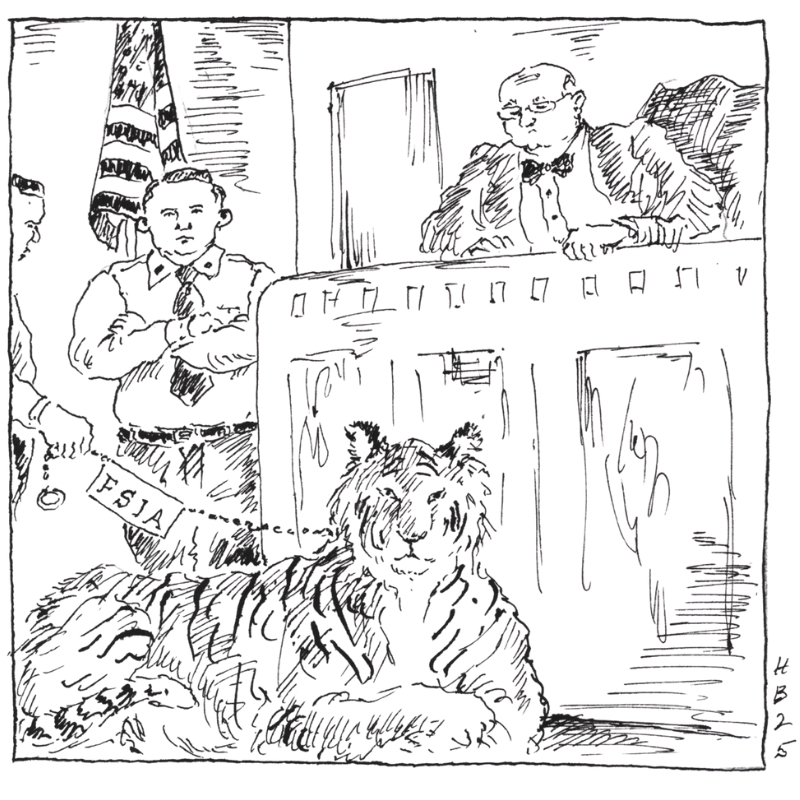

Supreme Court holds that FSIA § 1330 provides exclusive statutory test for personal jurisdiction over foreign states in arbitration award enforcement action:

Courts need not conduct additional "minimum contacts" analysis when FSIA arbitration exception applies and service is proper.

CC/Devas (Mauritius) Ltd. et al. v. Antrix Corp. Ltd. et al., 605 U.S. (2025).

The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) establishes the exclusive framework for obtaining jurisdiction in U.S. courts over foreign states and their instrumentalities such as state-owned entities. While foreign sovereigns generally enjoy immunity from suit, the FSIA creates several enumerated exceptions to such immunity. Among these is the arbitration exception under Section 1605(a)(6), which waives immunity for suits to confirm arbitration awards where the "agreement or award" is "governed by a treaty or other international agreement," such as the New York Convention, which requires signatory states to enforce international arbitration awards.

Under the FSIA § 1330, federal subject-matter jurisdiction is established if one of the enumerated exceptions to immunity applies. The statute's plain language states that when an immunity exception applies and proper service is made, personal jurisdiction automatically exists.

Despite seemingly clear statutory language, however, some federal courts, notably the Ninth Circuit, have imposed as an extra requirement for personal jurisdiction an additional showing of "minimum contacts" with the United States sufficient to satisfy the due process test for personal jurisdiction established in International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310 (1945) and its progeny. These courts essentially grafted the traditional due process analysis for personal jurisdiction in ordinary cases onto the FSIA's statutory framework, requiring plaintiffs to demonstrate both an applicable exception to immunity and extra-textual "minimum contacts" with the forum.

In Devas, the Supreme Court unanimously rejected this approach, holding that the FSIA provides the complete and exclusive test for personal jurisdiction over foreign sovereigns. The Court emphasized that Section 1330(b)'s plain language requires only two elements: that an immunity exception applies and that proper service is made. When both criteria are satisfied, personal jurisdiction "shall exist," and courts have no discretion to impose additional requirements.

The underlying dispute in Devas arose from a satellite-leasing agreement between Antrix Corporation Ltd., a commercial arm of the Indian Space Research Organization owned by the Republic of India, and Devas Multimedia Private Ltd., a privately owned Indian telecommunications company. When the government required Antrix to terminate the agreement prematurely, Devas disputed the termination and invoked the contract's arbitration provision. In September 2015, the tribunal awarded Devas $562.5 million in damages plus interest.

After successfully confirming the arbitration award in France and the United Kingdom, Devas petitioned the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington to confirm the award, relying on the FSIA's arbitration exception as the jurisdictional basis. The District Court confirmed the award and entered a $1.29 billion judgment against Antrix. On appeal, the Ninth Circuit reversed. Although affirming that Antrix qualified as a "foreign state" under the FSIA, the arbitration exception to immunity applied, and proper service had been made, the court applied its precedent requiring a "traditional minimum contacts analysis" under International Shoe to conclude that personal jurisdiction under the statute was not established because Antrix lacked sufficient suit-related contacts with the United States.

In reversing, the Supreme Court noted that Section 1330(b) contains no reference to "minimum contacts" and declined to "add in what Congress left out," explaining that "the FSIA was supposed to 'clarify the governing standards,' not hide the ball." The Court acknowledged that the FSIA's immunity exceptions themselves require varying degrees of suit-related domestic contacts, but emphasized that to the extent these exceptions satisfy International Shoe, "it is only because the exceptions Congress wrote happen to meet that standard, not because §1330(b) secretly incorporated our jurisdictional due-process cases." The FSIA "comprehensively regulates the amenability of foreign nations to suit in the United States," and Congress deliberately tied the immunity and jurisdictional provisions together. Whenever an exception applies, immunity falls away and jurisdiction follows. Reading an additional minimum-contacts requirement into only one of the FSIA's "tethered immunity and jurisdictional provisions . . . would weaken the link Congress forged and create a gap in the Act's otherwise comprehensive framework." The Court rejected the Ninth Circuit's reliance on earlier precedent that had interpreted one immunity exception's "direct effect" language as embodying the minimum-contacts standard, explaining that "the fact that one of the immunity exceptions contains language resembling the minimum-contacts test says little about whether a jurisdictional provision located elsewhere categorically imposes that test."

Importantly, the Court declined to address Antrix's alternative argument that the additional minimum contacts analysis was nevertheless required by the Fifth Amendment's due process clause, because the Ninth Circuit had relied exclusively on its interpretation of FSIA § 1330, and the lower courts had not yet addressed these contentions. It has been argued, and some courts have held, that while foreign states themselves are not accorded due process rights, state-owned entities qualifying as "Foreign States" under the FSIA may be entitled to the same due process rights as other juridical persons. Gater Assets Limited v. AO Moldovagaz, 2 F.4th 42, 53 (2d Cir. 2021). Thus, on remand, the lower courts may consider whether the Fifth Amendment's Due Process Clause itself requires a showing of minimum contacts before a federal court can exercise personal jurisdiction over a foreign state's instrumentality, meaning this issue could be back before the Court as a constitutional question, rather than one of mere statutory interpretation.

Read the court's full decision here.

Second Circuit joins other circuits in holding that the New York Convention is not reverse-preempted by state insurance laws under the McCarran-Ferguson Act:

Convention provision requiring domestic courts to recognize international arbitration agreements is self-executing and thus not an "Act of Congress" subject to reverse-preemption.

Certain Underwriters at Lloyds, London v. 3131 Veterans Blvd LLC; MPIRE Properties LLC, Nos. 23-1268-cv, 23-7613-cv (2d Cir. May 8, 2025).

The Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) requires the enforcement of arbitration agreements. Under ordinary preemption principles, the FAA preempts state laws that would invalidate an arbitration agreement. However, another federal statute, the McCarran-Ferguson Act (MFA), creates an exception to the normal rules of federal preemption by providing that state laws regulating the business of insurance supersede "acts of Congress" that would otherwise apply (unless the federal law specifically relates to insurance). Several states have enacted statutes prohibiting the arbitration of insurance disputes, which, under the MFA, will ordinarily preempt the FAA as respects its application to arbitration clauses in insurance policies. But when the policy is issued by foreign insurers such arbitration agreements fall under the New York Convention. This gives rise to the question of whether MFA reverse-preemption applies to those international arbitration agreements for which the Convention mandates enforcement. The First, Fourth, Fifth and Ninth Circuits have held that MFA reverse-preemption does not apply when the conflict is between state insurance laws and the United States' obligations to enforce international arbitration agreements under the New York Convention. But until 3131 Veterans, Second Circuit precedent held that state insurance laws could invalidate international arbitration agreements. (See Arbitration in the Courts, Vol. 12).

The Second Circuit has now reversed course and joined its sister circuits in holding Article II, Section 3 of the Convention, which requires the enforcement of arbitration agreements falling under the Convention, is self-executing and therefore not subject to MFA reverse-preemption by state insurance laws.

The underlying disputes arose from commercial property insurance policies issued by underwriters at Lloyd's, London covering two Louisiana properties. In 2021, Hurricane Ida damaged the insured properties, and the insureds (3131 Veterans and Mpire) sought coverage under the Lloyd's policies. When the property owners were dissatisfied with the insurers' settlement offers, they filed suit in Louisiana state court. The insurers, in turn, petitioned the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York to compel arbitration under the FAA and the New York Convention pursuant to an identical arbitration clause in each policy requiring such disputes to be resolved by arbitration in New York.

The district court denied the petitions, following the Second Circuit's prior decision in Stephens v. American International Insurance Co., 66 F.3d 41 (2d Cir. 1995) ("Stephens I"), which held that the New York Convention was not self-executing, but instead required the enabling legislation in Chapter 2 of the FAA to be effective under federal law. According to Stephens I, MFA reverse-preemption applied even to arbitration clauses falling under the Convention, because such agreements were only made enforceable by an "Act of Congress" (i.e., Chapter 2 of the FAA). The district court therefore found that a Louisiana state statute prohibiting the arbitration of insurance disputes prevailed over the Convention and precluded arbitration.

On appeal, the Second Circuit reconsidered its holding in Stephens I in light of the Supreme Court's subsequent decision in Medellín v. Texas, 552 U.S. 491 (2008), which established a new framework for determining whether treaty provisions are self-executing. The court concluded that, under Medellín, Article II, Section 3 of the Convention is in fact self-executing, because it contains a mandatory directive to U.S. courts to enforce agreements falling under the Convention. Accordingly, the U.S.'s treaty obligations under the Convention did not depend upon an act of Congress such as the FAA to take effect under federal law, the MFA did not apply, and the Convention preempted Louisiana's anti-arbitration statute as applied to the arbitration clauses in the policies issued by the foreign insurers.

The decision brings the Second Circuit in line with the First, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Circuits in holding that state insurance laws cannot preclude arbitration pursuant to an agreement falling under the Convention.

Read the court's full decision here.

Federal court holds Louisiana statute precludes domestic insurers who issued policies jointly with foreign insurers from compelling arbitration under New York Convention:

New York Convention did not govern arbitration clause where insurance policy explicitly created separate contracts between the policyholder and each insurer.

Brothers Petroleum, LLC v. Certain Underwriters at Lloyd's, No. CV 23-445 (E.D. La. Apr. 22, 2025).

As just discussed, the Second Circuit's decision in Certain Underwriters at Lloyds, London v. 3131 Veterans Blvd LLC) brought that court in line with other federal appellate rulings that, when an arbitration clause appears in a policy issued by a foreign insurer it is governed by the New York Convention and therefore, because the U.S.'s treaty obligations are not "acts of Congress," the MFA is inapplicable and state law cannot invalidate such agreements.

However, what is the proper result where foreign and domestic insurers jointly issue a policy containing an arbitration clause? In that situation, can domestic insurers compel arbitration under the New York Convention despite state laws prohibiting arbitration clauses in insurance contracts? The Fifth Circuit (which has jurisdiction over appeals from Louisiana federal courts) has previously held that the Convention requires arbitration in such cases because there is one agreement and one arbitration clause among the policyholder and both its domestic and foreign insurers. (See Bufkin Enterprises, LLC v. Indian Harbor Insurance Co., 96 F.4th 726 (5th Cir. 2024)).

In Brothers Petroleum, the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana addressed a twist on this fact pattern. Although foreign and domestic insurers jointly issued a single policy form containing a single arbitration clause, the document stated explicitly that it constituted a separate contract between the insured and each insurer. In those circumstances, the court held, there is no foreign party to the arbitration agreement between the policyholder and its domestic insurers. Thus, the Convention is inapplicable and the arbitration agreement, as between each domestic insurer and the policyholder, is governed by Chapter 1 of the FAA rather than the Convention. In that case, Louisiana's statute prohibiting the arbitration of insurance disputes reverse preempted the FAA under the MFA and invalidated the arbitration agreement as between the policyholder and the domestic insurers.

Read the court's full decision here.

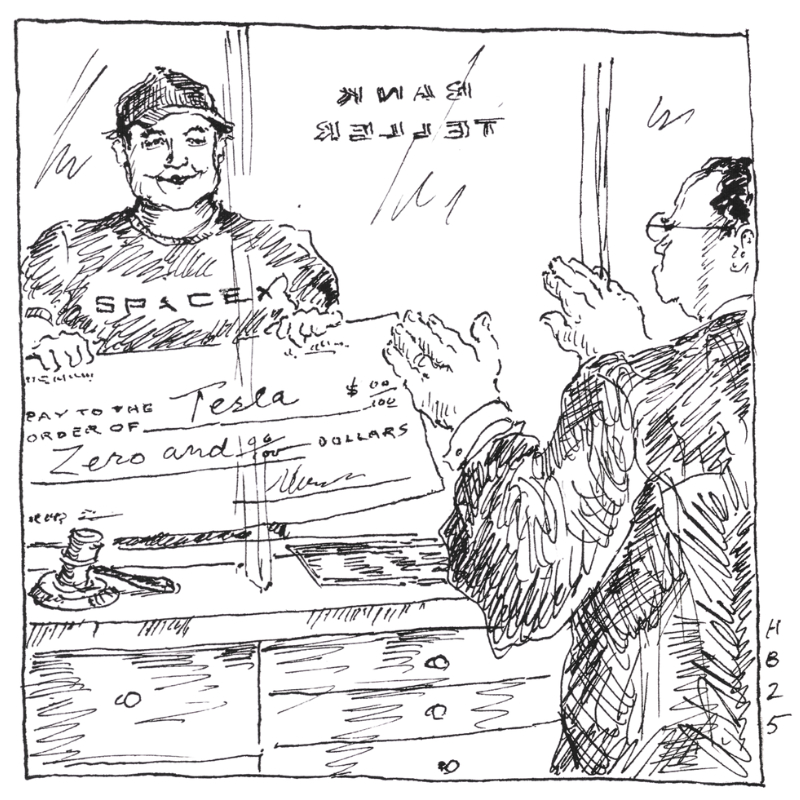

Ninth Circuit Holds District Court Lacked Jurisdiction to Confirm Zero-Dollar Domestic Arbitration Award:

Facts establishing jurisdictional amount in controversy must appear on face of petition to confirm domestic arbitration award, and court cannot "look through" to underlying dispute.

Tesla Motors, Inc. v. Balan, No. 22-16623 (9th Cir. Apr. 14, 2025).

Federal courts are courts of limited jurisdiction, which Congress and the Constitution have defined to include two main categories: "diversity" jurisdiction (suits between citizens of different states or between U.S. and foreign citizens) and "federal question" jurisdiction (suits involving claims arising under federal law). In most cases, federal courts have "federal question" jurisdiction over claims based on federal law, such as where the cause of action arises under a federal statute. But Chapter 1 of the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA), which governs domestic arbitration awards, does not itself confer federal question jurisdiction over actions to enforce domestic arbitration awards. (Chapter 2 of the FAA (§ 203) does confer federal question jurisdiction over international matters "falling under" the New York Convention.) Thus, federal courts require an independent jurisdictional basis to confirm or vacate domestic arbitration awards under FAA § 9. Most often jurisdiction over a Section 9 petition will be found, if at all, under the diversity jurisdiction statute (see 28 U.S.C. § 1332), which grants federal courts jurisdiction over disputes between citizens of different states where the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000.

In 2022, the Supreme Court in Badgerow v. Walters clarified that the basis for jurisdiction over petitions to confirm an award under FAA §9 must appear on the face of the petition. Where the petitioner invokes diversity jurisdiction, this means the petition must demonstrate that the award to be enforced arose out of an arbitration between citizens of different states and grants relief for at least $75,000. (In contrast, the court may look through the petition to the nature of the underlying claim to find jurisdiction over a petition to compel arbitration under FAA § 4. If that claim would, save for the arbitration clause, be subject to federal jurisdiction, the federal court has jurisdiction the hear the petition to compel. See Arbitration in the Courts Report, Vol. 7 (discussing Badgerow).) In Tesla v. Balan, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that Badgerow precluded jurisdiction over a petition to confirm a zero-dollar arbitration award because it did not satisfy the $75,000 amount-in-controversy requirement for diversity jurisdiction.

The underlying dispute arose in 2019 when Cristina Balan, a former Tesla automotive design engineer, filed suit against Tesla in the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington. Balan alleged that, in response to a 2017 Huffington Post article featuring her, Tesla defamed her by accusing her of stealing company money and resources during her employment.

Tesla moved to compel arbitration based on an arbitration clause in Balan's employment agreement. After initial litigation over the scope of arbitrable claims, the Ninth Circuit dismissed the case, finding that Balan's entire defamation claim against Tesla was arbitrable. During the arbitration, Balan amended her demand to add Elon Musk as a party, asserting a separate defamation claim against him based on a statement he made in August 2019.

The arbitrator ultimately issued an award dismissing both defamation claims as time-barred under California's one-year statute of limitations. Tesla and Musk then petitioned the Northern District of California to confirm the arbitration award, which the district court granted. Balan appealed.

The Ninth Circuit vacated the confirmation order, holding that the district court lacked subject matter jurisdiction. The court explained that under Badgerow, the facts establishing jurisdiction—such as the amount in controversy for diversity jurisdiction—must appear on the face of the confirmation petition. Since the arbitrator had awarded no damages and the district court cannot "look through" the petition to find jurisdictional facts in the underlying dispute, Tesla's petition could not satisfy the amount-in-controversy requirement. In other words, whether the underlying claim in arbitration would have itself conferred federal jurisdiction is irrelevant in determining jurisdiction over an action to confirm an award.

Read the court's full decision here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.