- within Privacy topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Technology and Law Firm industries

- within Privacy topic(s)

- in United States

- within Privacy, Insurance, Government and Public Sector topic(s)

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit and Law Firm industries

Pursuant to Section 6(c) and 61-62 of the Nigeria Data Protection Act (NDPA), the Nigeria Data Protection Commission (NDPC) is empowered to create an implementation framework to make the operationalisation of the Act easy. To this end, the General Application and Implementation Directive (GAID) was issued by the Commission (NDPC) on March 20, 2025, marking a paradigm shift in how personal data is handled within the nation's borders and beyond. By the provision of Article 3 (3), the GAID replaces the defunct Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR) and its Implementation Framework effective from the 19th September 2025.

This development marks a paradigm shift in Nigeria's data protection landscape, strengthening the legal infrastructure for personal data protection and imposing more defined obligations on businesses. For organisations operating in or targeting Nigeria, the GAID is not only a compliance manual but also a regulatory compass for aligning their data handling practices with both domestic law and global standards.

This article explores the key provisions in the GAID and analyses their practical implications for businesses.

1. Regulatory Supremacy and Harmonisation

One of the most consequential innovations in the GAID is the explicit declaration that the NDPA is the supreme legal authority governing data protection in Nigeria. Under Article 3(1) of the GAID, the Directive affirms that in any case of inconsistency between any law, regulation, or guideline and the processing of personal data under the NDPA, the provisions of the NDPA shall prevail. Furthermore, GAID Article 3(2) stipulates that should there be a conflict between the NDPA and the GAID itself, the NDPA prevails. The GAID also formally retires the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR) 2019 from use as a binding instrument: GAID Article 3(3) directs that upon issuance, the NDPR ceases to be applied, although actions taken under it prior to GAID's issuance remain valid.

2. Elevated Compliance Obligations for Businesses

Under the GAID, compliance is no longer passive or reactive but a continuous and demonstrable duty. Article 7 of the GAID sets out general compliance measures, requiring that data controllers and processors register (when designated as "of Major Importance"), conduct periodic audits, and integrate compliance into their operations. For controllers and processors classified as Ultra-High Level (UHL) or Extra-High Level (EHL), Article 10 mandates the submission of Compliance Audit Returns (CARs) annually, using a template prescribed in Schedule 2 of the GAID.

In parallel, the GAID requires entities engaging in high-risk data processing to conduct Data Privacy Impact Assessments (DPIAs)1 and to embed the outcomes in their audit returns. Finally, controllers are obligated to notify the NDPC of personal data breaches within 72 hours, consistent with Section 40 of the NDPA (integrated through GAID). For businesses, this means shifting from a checklist mentality to a culture of continuous oversight, record-keeping, internal audit, and risk assessment, as well as preparing for regulatory scrutiny and enforcement based on substantive performance, not just documented formality.

3. Categorisation of Data Controllers and Processors of Major Importance

The GAID refines the concept of "Data Controller/Processor of Major Importance (DCPMI)" introduced in Section 65 of the NDPA by delineating sub-tiers with graduated obligations. Article 8 of the GAID clarifies that an entity "operating in Nigeria" includes targeting Nigerian data subjects, even without physical presence.

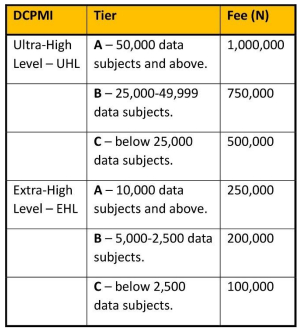

Under this approach, the GAID divides DCPMIs into three tiers: Ultra-High Level (50,000+ data subjects), Extra-High Level (10,000–49,999), and Ordinary-High Level (2,500–9,999). The thresholds and associated registration fees are detailed in Schedule 7 of the GAID.

NEW NDPA COMPLIANCE AUDIT RETURNS FILING FEE

From a business perspective, this stratification means that an organisation processing large volumes of personal data must budget for higher audit costs, while entities in lower tiers face lighter burdens. Critically, even foreign entities with no Nigerian base but whose services target Nigerians fall under the scope.

4. Empowerment and Protection of Data Protection Officers

The GAID strengthens the DPO role through dedicated provisions in Articles 11 through 14. Under Article 11, DCPMIs must appoint a DPO. Article 12 outlines organisational support obligations: the DPO must have access to all processing activities, adequate resources, training, and independence, with protection from dismissal or penalisation for performing their role. Article 13 introduces the requirement that DPOs submit semiannual data protection reports to management, covering topics such as privacy notices, DPIA outcomes, breach incidents, and legal basis assessments. Article 14 requires the NDPC to conduct Annual Credential Assessments (ACA) of DPOs based on metrics in Schedule 3 of GAID.

For businesses, compliance demands more than naming a DPO: the person must be empowered, insulated, resourced, and technically competent. Organisations will need to build systems to support reporting, oversight, and DPO credentialing.

5. Reliance on Lawful Basis

Pursuant to Section 25 of the NDPA and in line with Articles 16–27 of the GAID, a data controller must carefully assess and determine the lawful basis for processing personal data before commencing such processing activities. The lawful bases recognised under the NDPA and GAID includes consent, contractual obligation, legal obligation, vital interest, public interest and legitimate interest.

As provided in Article 16(3) GAID, the responsibility for determining the lawful basis rests with the data controller, who defines the purpose of the processing. A data controller must be able to demonstrate accountability and justification for its reliance on any lawful basis, especially during audits or regulatory investigations.

In line with Article 23 GAID, reliance on any lawful basis shall be evaluated against principles of necessity, proportionality, and duty of care, ensuring that the fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject are not undermined. Additionally, Sections 37 and 45 of the 1999 Constitution provide the overarching constitutional safeguards for privacy, which serve as a benchmark for evaluating any derogation under the NDPA.

Accordingly, before embarking on any processing activity, the data controller must:

a. Clearly identify and document the lawful basis relied upon.

b. Provide transparent notice to data subjects in line with Section 27 NDPA and Article 27 GAID.

c. Ensure that reliance on the lawful basis is not misapplied or used to circumvent consent requirements, particularly in high-risk or rights-sensitive processing.

6. Data Privacy Impact Assessment (DPIA)

Businesses must now conduct DPIAs before undertaking high-risk data processing such as profiling, automated decision-making, or handling sensitive personal data.2 This creates an additional compliance step that requires time, certified expertise, and filing with the NDPC, but it also reduces liability by embedding privacy by design and providing regulators with early assurances of accountability

7. Monitoring, Evaluation and Maintenance of Data Security Systems

Companies are required to establish and routinely update schedules for testing, monitoring, and certifying their data security systems, covering people, processes, and technology.3 This means investing in regular training, vulnerability tests, and system updates, which may increase operational costs but enhances resilience against breaches and regulatory scrutiny.

8. Internal Sensitisation and Training on Privacy

The Directive mandates internal privacy training and compliance awareness programmes.4 Businesses must adopt structured sensitisation schedules, policies, and checklists to keep employees and contractors aware of obligations. While this requires ongoing resources, it strengthens organisational culture and reduces human-error risks in data handling.

9. Deployment of Data Processing Software

Before launching or updating software that processes personal data, businesses must conduct a DPIA, embed privacy by design, and provide clear in-app privacy notices.5 This raises compliance costs for tech companies and software developers but also improves consumer trust and legal defensibility in case of disputes.

10. Measures Against Privacy Breach Abetment.

Organisations must prevent their platforms from being used to facilitate privacy violations and must comply with NDPC directives to restrict offenders.6 Non-compliance exposes companies to liability as if they directly committed the breach.

11. Data Breach Notification

Firms must notify the NDPC within 72 hours of becoming aware of a breach and inform affected individuals immediately7 . This accelerates incident-response timelines, requiring companies to maintain strong breach-detection, reporting, and communication systems to avoid penalties and reputational harm.

12. Data Processing Agreements (DPAs)

Businesses engaging processors must formalise their relationships with detailed Data Processing Agreements covering responsibilities, risks, and compliance measures.8 This imposes due-diligence and contractual burdens but helps organisations allocate liability, demonstrate accountability, and avoid regulatory sanctions for third-party misconduct.

13. Benchmarking with Interoperable Data Privacy Measures (IDPMs)

The Directive encourages companies to adopt internationally recognised data privacy best practices, subject to NDPC approval.9 While aligning with global standards may require additional compliance effort and expert input, it enhances cross-border credibility and prepares Nigerian businesses for interoperability in global data flows.

14. Strengthening Data Subject Rights

The GAID fleshes out the data subject rights established under Part VI of the NDPA. Articles 36 to 39 of the GAID collectively provide much-needed clarity on the enforcement of data subject rights under the Nigeria Data Protection Act 2023. They codify the rights to rectification, portability, erasure (the "right to be forgotten"), and the right to lodge complaints with the Commission, while removing barriers such as the need for affidavits or payment for correcting controller-driven errors. The provisions emphasise accountability by requiring controllers to prove that data subjects were given ample opportunity to verify their data and by ensuring portability applies only in appropriate contexts such as consent or contractual necessity. They also balance the right to be forgotten with public interest, legal obligations, and constitutional safeguards, thereby preventing abuse of the right while still protecting individuals against unlawful or excessive processing.

Importantly, the clear procedure for filing and investigating complaints, including timelines, obligations on controllers, and the Commission's remedial powers, strengthens the enforcement framework. Taken together, these Articles not only expand the practical scope of individual rights but also provide clear operational duties for businesses, thereby reducing ambiguity and embedding enforceability into Nigeria's data protection landscape.

A particularly novel provision is Article 40, which introduces the Standard Notice to Address Grievance (SNAG) mechanism. Under this mechanism, data subjects (or representatives or civil society actors) may issue a structured internal notice to controllers before lodging a formal complaint with the Commission. The controller must respond and report the decision back to the Commission via its electronic platform.

Businesses must now ensure they have well-designed channels and internal processes to respond to subject requests and SNAGs, including timeframes, remediation workflows, and escalation protocols.

15. Emphasis on Data Ethics and Accountability

The GAID goes beyond mere legal compliance by embedding data ethics into its structure. Article 41 affirms that personal data remains the domain of the individual and that organisations act as custodians subject to the data subject's objections. Article 42 requires demonstrable transparency, fairness of intent, autonomy, proportionality, and outcome assessment, including the need to evaluate risks and impacts even where processing is technically lawful.

In practice, businesses must adopt a mindset that asks not only, "Is this lawful?" but also, "Is this justifiable and respectful?" particularly in marketing, profiling, algorithmic decisions, and data monetisation. Ethical lapses may attract scrutiny, reputational harm, or investigations, even absent a direct violation.

16. Regulation of Emerging Technologies

Article 43 of the GAID addresses the deployment of emerging technologies (ETs) such as artificial intelligence, IoT, and blockchain. It mandates that controllers document technical and organisational parameters, file those as part of their CAR submissions, conduct DPIAs focused on disparate impact and the vulnerability index of data subjects, and test technologies in low-risk settings before full deployment. Additionally, Article 44 tasks the Commission with assessing privacy and public interest parameters for ETs, ensuring alignment with human rights and international best practice. For technology firms, this means privacy concerns must be frontloaded in design and testing, documented thoroughly, and justified in regulatory filings, not treated as afterthoughts.

17. Cross-Border Data Transfers

The GAID's cross-border regime is embodied in Article 45, which anchors Part VIII of the NDPA as the governing standard under Section 63. Article 45(2) instructs that pending further regulations, the explanatory note in Schedule 5 should guide adequacy assessments and other transfer grounds. Article 45(3) requires the Commission to consider enforcement of fundamental rights in target jurisdictions when judging adequacy.

Under the GAID, there are three permissible mechanisms for cross-border transfer: an adequacy decision, CrossBorder Data Transfer Instruments (CBDTIs) (e.g., codes, certifications, binding rules or contractual clauses), or other lawful bases such as explicit consent or contractual necessity.

In operational terms, multinational companies must re-evaluate their intragroup or cloud-based transfer arrangements, ensure contractual safeguards, monitor adequacy determinations, and include transfer justifications in CAR filings.

CONCLUSION

The NDPA GAID represents a new compliance era for businesses in Nigeria. As enforcement begins, businesses should prioritise:

i. Gap assessments against NDPA/GAID obligations.

ii. DPO appointment and empowerment.

iii. Registration and CAR filings (for DCPMIs).

iv. Implementation of DPIAs, breach response, and rights facilitation mechanisms.

v. Integration of ethics and privacy by design in emerging technology use.

Footnotes

1 Articles 7(o) and 28)

2 Article 28

3 Article 29

4 Article 30

5 Article 31

6 Article 32

7 Article 33

8 Article 34

9 Article 35

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.