- within Technology topic(s)

- within Technology, Law Department Performance and Compliance topic(s)

- with readers working within the Automotive and Law Firm industries

While Singapore's Draft Guidelines provide a starting point for lawyers thinking about guardrails in AI use, any policy must adapt to Indian realities

Generative AI is no longer just a buzzword in the legal profession. Law firms, in-house teams, and independent practitioners are actively experimenting with GenAI to streamline time-consuming tasks like drafting, legal research, contract review, and due diligence.

But the flip side is that GenAI use comes with real risks. Confidential client data could slip out. AI 'hallucinations' in the form of fabricated cases and citations have already embarrassed lawyers before courts in India. And more than many other professions, lawyers are strictly bound by duties of confidentiality, privilege, and accuracy.

As fresh risks emerge with each stage of the technology's evolution, global consensus on regulating GenAI is evolving. But most regulatory efforts focus on developers, and not the professionals actually using these tools.

Lawyers, however, are inherently risk-aware, and their deep understanding of legal obligations makes them attuned to the potential pitfalls of emerging technologies. They know GenAI could transform the way they work, but they're also sensitive to the risks of using it without clear guardrails. The dilemma raises the question: what can be done to improve lawyers' confidence towards adoption?

The Singapore Draft Guidelines

Singapore's 'Draft Guidelines for Using Generative AI in the Legal Sector' represent a key development in this context. The Draft Guidelines, which were released for public consultation in September 2025, go beyond general principles by providing practical safeguards tied to specific AI use cases. They are designed with the legal profession in mind, addressing risks such as confidentiality, privilege, and conflicts of interest. They also tie the safeguards back to professional obligations under Singapore law, which makes the advice feel grounded and actionable.

Here are some salient features:

Governance and adoption

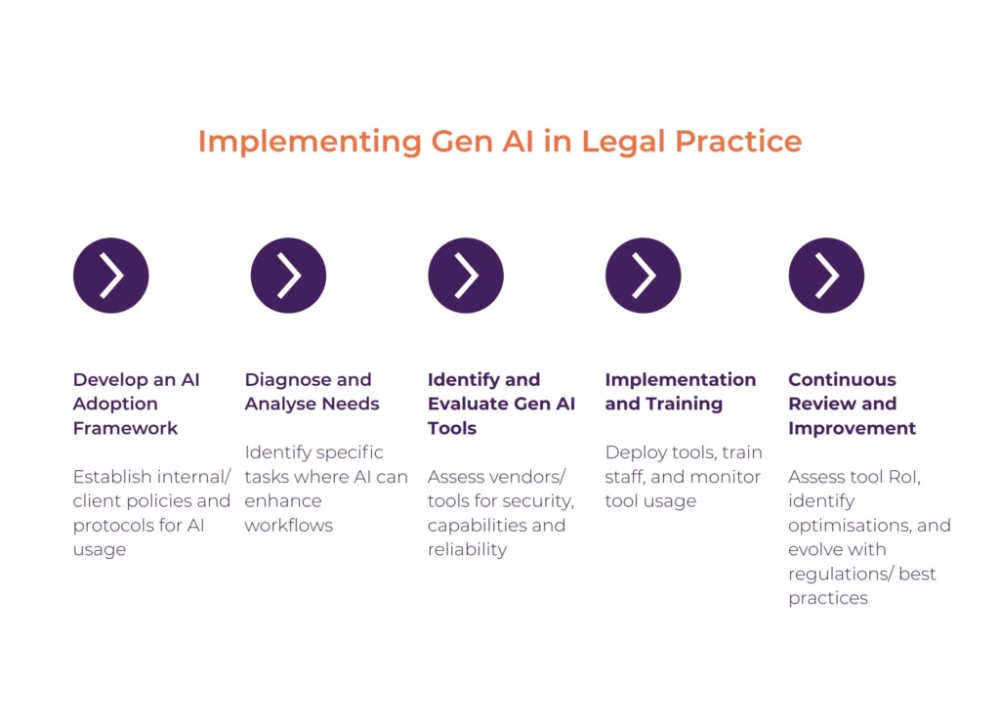

The Draft Guidelines provide step-by-step guidance for legal teams adopting GenAI—from designing an overarching governance framework, to assessing third-party tools, implementation and training, and finally monitoring and evaluation. This covers not only governance and risk management, but also tool performance and effectiveness.

Illustrative risks and safeguards

The Draft Guidelines flag common risks when using GenAI for tasks such as research, document review, contract analysis, and drafting. These include misuse of client data, reliance on hallucinated outputs, and system integration issues. They also provide suggestions for measures and safeguards such as:

Internal controls: Staff should anonymise sensitive inputs, follow verification protocols to detect errors, and maintain strict access controls to prevent conflicts of interest. Output quality should be ensured through precise prompt design, human review, template management, and regular monitoring.

External controls: Vendors should be vetted for data security, breach response, certifications, and cross-border safeguards. Tools should support source citations to facilitate fact-checking.

Professional considerations

The Draft Guidelines go beyond general risks to help lawyers view GenAI in the context of their unique obligations under Singapore law, including the Legal Profession Act 1966 and corresponding rules. By linking recommended safeguards directly to professional duties, the Draft Guidelines help lawyers navigate technological and legal risks in a cohesive framework.

A blueprint for India?

Although developed for Singapore, the Draft Guidelines could provide a valuable starting point for Indian law firms, in-house legal teams, and service providers. However, responsible adoption in India must ultimately be grounded in the country's unique legal, operational, and practical realities.

Scale and resource challenges

While the recommended stages of AI governance (tool assessment, training and implementation, monitoring performance) remain broadly applicable within India, smaller firms, independent practitioners, and in-house teams may not have the resources to implement complex governance systems. In such instances, simple trackers, checklists or spreadsheets may be more feasible compared to investments in large-scale monitoring platforms or dashboards.

Infrastructure and operational realities also shape how lawyers in India manage risk. Cloud-based GenAI tools may face slow or unreliable internet in some offices or courts. Limited staff bandwidth may mean fewer layers of review. Varying levels of legal tech literacy among clerks and court staff could impact accuracy and confidentiality. These factors should influence how AI risk is managed across the lifecycle of an Indian legal team.

Professional and ethical obligations

Given the parallels between the laws governing the legal profession in Singapore and India, Indian lawyers may also refer to the Draft Guidelines for guidance on how to use GenAI while upholding legal obligations and the professional code of conduct.

- Confidentiality: Client–lawyer communications are protected under India's evidence law1 and reinforced by the Advocates Act, 1961, read with the BCI Rules2. This duty would apply equally when using GenAI tools for client work. Lawyers must therefore assess how such tools handle client data. Is the data stored or not? Is it used to train the Large Language Model the system is based on? Is it shared with third parties? The concern about breaching client confidentiality is real. For instance, OpenAI recently announced that it may report user interactions if it detects potential illegal activity. Similar concerns arise with AI-powered notetakers, where meeting transcripts may automatically be shared with participants beyond the client, or stored on third-party servers.

- Transparency: Lawyers must disclose any interest in a matter that could reasonably affect a client's judgement to engage them.3 Read together with the duty not to misuse client confidence, the underlying principle is that any information that may influence the decision to retain the lawyer should be shared with the client. Disclosure of AI use in client work may be seen as part of this broader obligation.

- Human verification: The BCI Rules prohibit any attempt to influence the decision of a court through illegal or improper means.4 Lawyers need to be cautious about presenting AI-generated outputs in court without human verification, as this could mislead the court and compromise professional integrity.

- Accountability: Advocates are required to uphold their clients' best interests by fair means.5 This obligation places ultimate accountability on lawyers and any errors or omissions, including by GenAI, must remain theirs.

Apart from these common principles, laws governing the legal industry in India also mandate some unique requirements. To take an example, the restriction on solicitation and advertising6 raises a compelling question in our context: would announcing AI use or partnerships with AI providers be considered advertising?

Singapore's Draft Guidelines are not a ready-made solution for India, but they offer a model for balancing the generational opportunity presented by AI with the duties and risk-related challenges of the legal profession. In any framework that is developed in India—both at the public and private level—it will be important to consider how professional conduct rules intersect with AI use. The overall challenge will be to build a playbook that harnesses the potential of the technology while maintaining allegiance to the profession's oldest commitments: client trust, professional integrity, and accountability.

Footnotes

1 Section 134, Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023

2 BCI Rules, Part VI, Chapter II – Rules 17, 24

3 BCI Rules, Part VI, Chapter II, Rule 14

4 BCI Rules Part VI, Chapter II, Rule 3

5 BCI Rules, Part VI, Chapter II, Rule 15

6 BCI Rules, Part VI, Chapter II, Rule 36

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.