- within Finance and Banking topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Advertising & Public Relations, Utilities and Law Firm industries

- within Law Department Performance, Consumer Protection and Wealth Management topic(s)

Ring-fencing was a key component of the UK's response to the financial crisis of 2008–2009. As has been widely acknowledged, subsequent regulatory reforms in banking regulation (in particular, those relating to capital, liquidity, Total Loss-Absorbing Capacity (TLAC) and resolution) have largely accomplished the objectives that the introduction of ring-fencing intended to achieve. Further, the regime presents costs to the UK economy, diverts investment away from the real economy and impairs the competitive position of UK banks in international markets. This position is clearly at odds with the present UK Government's objectives on growth, as acknowledged by the Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, in her Mansion House speech on July 15, 2025.

In our view, there is therefore a strong case to be made for change. This paper seeks to identify the downsides and residual benefits of ring-fencing in the current regulatory environment, examine what a recalibration could entail, and propose a revised regime which retains those residual benefits while reducing the costs of the regime to the real economy. We believe that the revisions would improve the competitiveness of the UK banking sector and flow of funding to the real economy.

Background

Banks occupy a singularly privileged position within the UK's economy owing to their essential role in the financial system, yet the very attributes that render them indispensable are also the source of acute vulnerabilities. The inherent leverage of deposit-taking institutions, the mismatch between their short-term liabilities and longer-dated assets, and their centrality to payments and clearing systems mean that distress at any one large bank can propagate swiftly through the financial system, and imperil depositors, counterparties and ultimately the real economy. These systemic risks materialised spectacularly during the global f inancial crisis of 2007–2009, when the failure or near-failure of several globally active banks—including systemically important institutions in the UK—necessitated unprecedented taxpayer support, revealed deficiencies in existing prudential and resolution frameworks, and exposed the problem of the implicit guarantee that certain firms were "too big to fail".

The crisis prompted an extensive domestic and international policy response. At the international level, the Basel III framework introduced more stringent capital, liquidity and leverage standards. In Europe, legislators adopted extensive amendments to the capital requirements framework and introduced, and subsequently amended, the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive. Within the UK, the Government judged that more fundamental structural reform was necessary to restore market discipline and ensure the continuity of critical economic functions without recourse to public funds. Consequently, the Chancellor of the Exchequer established the Independent Commission on Banking (ICB) in June 2010, tasking it with considering reforms to enhance financial stability and promote effective competition. After more than a year of evidence gathering, economic modelling and public consultation, the Commission delivered its Final Report in September 2011, recommending, inter alia, the statutory ring-fencing of core retail banking activities, such as deposits and overdrafts, from non-retail activities such as investment banking and international banking. The ring-fencing regime passed into legislation in the Financial Services (Banking Reform) Act 2013 and associated statutory orders came into effect on January 1, 2019.

What's ring-fencing designed to do?

Ring-fencing is a uniquely British solution to the structural issues revealed by the crisis. The UK has a major international financial centre attached to a relatively small domestic economy. As a result, it has a large banking sector relative to GDP (over five times GDP in 2008, albeit that it has reduced somewhat since), which is relatively highly exposed to global financial markets.

Ring-fencing seeks to reduce the perceived risk of disruption in the provision of UK retail financial services arising from contagion from global financial markets by structurally separating retail banking activities from risks associated with activities conventionally conducted by international wholesale and investment banks.

Perimeter: Was ring-fencing aiming at the right target?

One question which was the subject of some debate when ring-fencing was being formulated was whether the underlying premise—that retail banking activities needed to be isolated from investment banking activities (sometimes dismissively referred to as "casino banking" post-crisis)— was the right one at all. In common with most banking crises, the crisis of 2007–2008 primarily manifested itself in the UK through losses associated with imprudent bank lending (including within the treasury function), coupled with excessive leverage. The major bank failures in the UK banking sector were of Bradford and Bingley and Northern Rock, each of which ran an operating model strikingly close to that of a ring-fenced bank.

How ring-fencing works

Architecture—perimeter and height

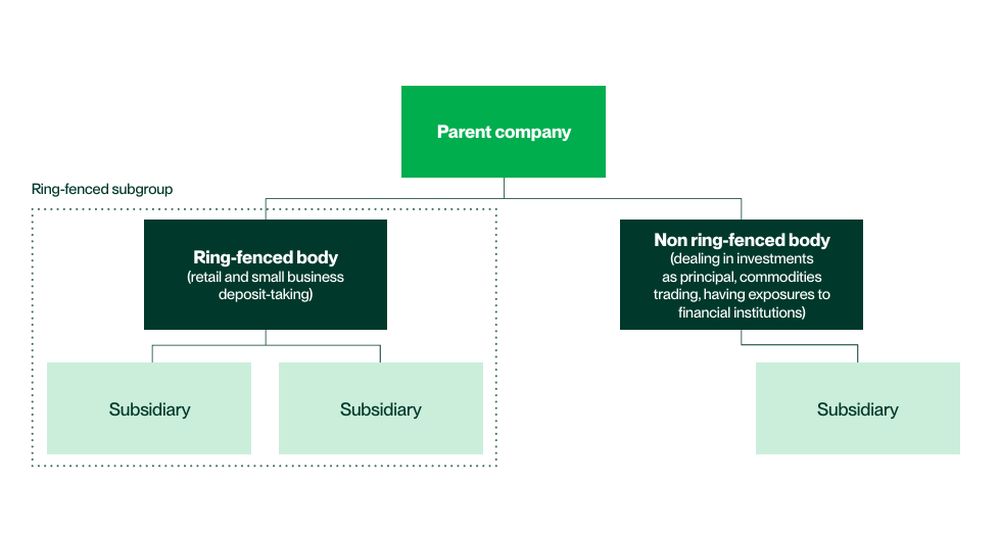

At its core, ring-fencing reflects a policy decision that certain retail banking activities ("core deposit activities"1), when engaged in at sufficient scale to pose systemic risk to the UK (currently a threshold of GBP35 billion2 of core deposits), should be isolated from risks associated with activities conventionally conducted by international wholesale and investment banks ("prohibited activities"3). Isolation is achieved by housing mandated activities in a separate legal entity (ring-fenced bank) within an in-scope group. Prohibited activities (primarily, in broad terms, proprietary dealing in investments and incurring exposures to other financial sector entities—so-called "relevant financial institutions", or RFIs) may not be carried on by a ring-fenced entity; an in-scope banking group which wishes to conduct prohibited activities must do so through a non-ring-fenced bank. (In practice, banking groups have multiple operating legal entities, including banks and non-banks. The perimeter rules extend to non-bank entities within an in-scope group too, resulting in the major UK banks having ring-fenced subgroups (including one or more ring-fenced banks) in wider, non-ring-fenced, groups).

The concepts of "mandated" and "prohibited" activities determine the "perimeter" of ring-fencing, as they determine what activities must take place within, or outside, the ring-fence. The perimeter is defined in statute.4 Until February 2025, the perimeter was also territorial, with ring-fenced banks (and their subgroups) unable to have branches, subsidiaries or participations outside the UK and EEA.5

As the legal structural separation of activities does not of itself fully isolate the ring-fenced bank from risks associated with prohibited activities, including those undertaken within its wider group, the regime also includes "height" rules designed to ensure that a ring fenced bank/subgroup is able to operate at a sufficient level of independence from the wider group. Responsibility for the "height" rules is delegated to the PRA, which is given an operational objective of discharging its general functions in a way which (broadly) ensures the continuity of "core services" (deposits, payment services and overdrafts)6 provided by ring-fenced bodies, and is obliged to make 'height' rules for "group ring-fencing purposes".7 The "height" rules impose standalone governance, financial (capital, large exposures and liquidity), operational and reporting requirements on ring-fenced banks (and ring-fenced subgroups) to give assurance that they could continue to operate notwithstanding insolvency of (or within) the wider group.

To further reinforce the resilience of ring-fenced banks (and their subgroups), the PRA also applies a regulatory capital surcharge (the other systemically important institutions (OSII) buffer), requiring ring-fenced banks (subgroups) to maintain a risk-weighted asset (and in some cases a leverage) capital buffer as specified by the PRA.8

A RING-FENCED BANKING GROUP—EXAMPLE CORPORATE STRUCTURE

Activities that can be performed by either:

- Deposit-taking for large corporates, building societies and other RFBs

- Having exposure to building societies and other RFBs

- Lending to individuals and corporates

- Holding own securitisations

- Trade finance

- Payment services

- Hedging liquidity, interest rates, currency, commodity and credit risks for itself

- Selling simple derivatives to corporates, building societies and other RFBs

International comparators

The UK ring-fence regime is unique. Structural separation is a feature of some banking markets—in particular, the U.S.— while prohibiting FDIC insured deposits from being used to fund investment banking activities does not prevent U.S. banks from having exposures to the financial sector. The EU looked at introducing structural reform via the Liikanen Report of 2012 but ultimately did not progress it.9 France and Germany each introduced a restriction on banks engaging in proprietary trading. Switzerland has no formal ring-fencing regime but as a supervisory matter encouraged its local systemic banks to subsidiarise their domestic banking business locally.

How has ring-fencing changed the UK banking sector?

As a result of the introduction of ring-fencing, affected UK banks were required to undergo ring-fencing projects which, for the major UK banks,10 involved bifurcating their business across the ring-fence. The major UK banks therefore undertook substantial restructuring programmes in the run-up to implementation, and now run separate ring-fenced and non-ring-fenced franchises. The split has had a number of consequences for the UK banking sector, its clients and the real economy.

Narrowing the investment of retail deposits

The regime reshaped how the UK retail banking system channels retail savings into investment. Ring-fencing affects this in two ways: f irst, by prohibiting redeployment of retail savings into prohibited activities; and secondly, by causing affected banks to split their service offerings in a way which has resulted in large corporate customers being serviced in the non-ring-fenced bank, while smaller customers are serviced in the ring-fenced bank. This has had a number of consequences.

Funding prohibited activities

It is a design feature of the regime that core deposits are prevented from funding prohibited activities. Ring-fenced banks cannot engage in prohibited activities and generally cannot invest in entities which do so (albeit that they may incur small exposures across the ring-fence under the height rules).

Further, how core deposits flow into permitted activities depends on the choices which each affected institution had to make as to how it drew up its operating model under the ring-fencing regime. In practice, most of the affected banking groups bifurcated their customer base to service larger commercial banking customers from the non-ring-fenced bank, with small and medium-sized customers (other than relevant financial institutions) being serviced from the ring-fenced bank.

The narrowing of the investment of the proceeds of core deposits has had a number of consequences for the UK market:

- At its most straightforward, ring-fenced bank deposits are by design not funding non-ring-fenced bank activities, and are funding larger corporate customers less than would otherwise be the case. Ring-fenced banks have a large, high-quality, "sticky" retail deposit base which is unavailable outside the ring-fence. The trapping of funding in the ring-fence creates a liquidity surplus in ring-fenced banks, and a corresponding liquidity deficit in non-ring-fenced banks which needs to be eliminated by obtaining liquidity from third parties.11 The inability of non-ring-fenced banks to access funding across the ring-fence:

- creates additional liquidity costs for in-scope groups, which must maintain separate liquidity buffers and access liquidity elsewhere;

- DZ increases the cost of funding for NRFBs given greater funding costs;12 and

- puts NRFBs at a competitive disadvantage relative to their more integrated international competitors (including those operating in the UK retail banking market under the GBP35bn threshold) which can (and do) deploy UK retail deposit funding more profitably across their franchise.

- The prohibited activities include a number of categories of investment in the real economy. In particular, although there has been some recent liberalisation, ring-fenced banks are highly constrained in their ability to acquire and hold shares. By way of example, all of the in-scope shareholders in the Business Growth Fund (the UK venture capital fund established and owned by the major UK banks following the crisis) hold their shares outside the ring-fence, notwithstanding the obvious alignment with their retail bank franchises. (Recent liberalisation to permit investment in SME funds does not permit migration into the ring-fence pending changes to the height rules discussed below).

Geographic concentration

The ring-fenced banks are overwhelmingly domestically focussed (as noted above they have until earlier this year been unable to have non-EEA presences and, in practice, they have limited non-UK business and exposure).13

Sectoral concentration

The combination of high capital requirements and the limits noted above have resulted in a high level of concentration in UK mortgage lending.14

Capital

As noted above, ring-fenced banks are subject to the OSII buffer, a ring-fence-specific capital buffer.15 The amount of Tier 1 capital attributable to the buffer across the affected banks runs into billions for each bank.16 This represents a drag on investment for the UK banking sector. Some ring-fenced banks are also subject to additional leverage ratio buffer requirements.

Implementation costs

Implementation took four to five years and is reported to have cost roughly GBP2.9bn.17

Footnotes

1. The legislation uses the terminology "core activities", "core services" and "core deposits". The term "core deposits" captures deposits held with a UK deposit-taker in a UK account from individuals and corporates. Exclusions exist for certain high net worth individuals (permitting private banking in the non-ring-fence) and high net worth organisations (Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Ring-fenced Bodies and Core Activities) Order 2014).

2. Changed from GBP25bn in February 2025.

3. We have used the term "prohibited activities" as a catch-all for the activities a ring-fenced bank cannot undertake. The legislative framework in fact describes two categories: excluded activities (in broad terms, dealing as principal in investments, set out in section 142D FSMA) and prohibitions, empowered by section 142E FSMA and set out in the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Excluded Activities and Prohibitions) Order 2014. In addition to "mandated activities" and "prohibited activities", there also exists a third, residual, category of "permitted" activities (such as commercial lending) which may be undertaken within and/or outside the ring-fence— we refer to these in this paper as "permitted activities".

4. Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Excluded Activities and Prohibitions) Order 2014.

5. The regime was introduced while the UK was still part of the European Union and it was considered contrary to EU law to have a narrower geographic perimeter.

6. Section 2B FSMA.

7. Section 142B FSMA.

8. The capital buffer required from January 1, 2025 is set out here: https://www. bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2023/november/ osii-buffer-rates-for-ringfenced-banks-and-large-building-societies.

9. High-level Expert Group on reforming the structure of the EU banking sector, Final Report, October 2, 2012, https://finance.ec.europa.eu/ document/download/e30ae267-9b3a-4be5-a3fb-4e268e7b6d67_ en?filename=liikanen-report-02102012_en.pdf.

10. Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, NatWest and Santander: see https://www. bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/prudential-regulation/ authorisations/which-firms-does-the-pra-regulate/2025/list-of-ring-fenced bodies.pdf. Santander is unique in being a foreign-owned group which is within the regime. Virgin Money was in scope until it was acquired by Nationwide Building Society on October 1, 2024.

11. The Ring-fencing and Proprietary Trading Independent Review Final Report (the Skeoch Review), page 11, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ media/6230b687e90e070ed9432345/CCS0821108226-006_RFPT_ Web_Accessible.pdf. The excess liquidity above internal liquidity targets held by the five largest RFBs was GBP120bn as of September 2021.

12. Skeoch Review, page 65. The additional cost of funding for NRFBs was an accepted cost of the ring-fencing regime in advance of the legislation being passed. At the time of the Skeoch Review, wider macroeconomic conditions (e.g., low bank rate and quantitative easing) had limited the actual impact on NRFBs' cost of funding, which is likely to have changed in the years since.

13. Skeoch Review, pages 78–79.

14. Skeoch Review, page 44. UK retail mortgages constituted more than 80% of RFBs' lending at the time of the report.

15. Building societies over a certain threshold must also maintain an OSII buffer.

16. For example, GBP3.82bn for Lloyds Banking Group (see Pillar 3 disclosures, https://www.lloydsbankinggroup.com/assets/pdfs/investors/financial performance/lloyds-bank-plc/2025/q1/2025-lb-q1-pillar-3.pdf).

17. Skeoch Review, page 14.

To read this article in full, please click here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]