- within Corporate/Commercial Law topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Business & Consumer Services and Healthcare industries

- within Law Department Performance and Energy and Natural Resources topic(s)

In 2013, Y Combinator, one of Silicon Valley's most influential startup accelerators (known for backing companies like Airbnb, Dropbox, and Stripe), introduced a financing instrument that would transform early-stage fundraising: the Simple Agreement for Future Equity, or SAFE.

What makes SAFE distinctive is its structure. It is neither debt nor equity. Unlike a convertible loan, SAFE has no maturity date, no interest, and no repayment obligation. With SAFE, the investor provides capital today in exchange for a contractual right to receive shares later without the legal and accounting complexities of debt instruments. For founders, SAFE offers speed and flexibility. For investors it provides prompt access to equity upside without the burden of monitoring loan terms.

Since its inception, SAFEs have become a popular fundraising instrument in the US inspiring the development of similar instruments across Europe. Yet Finland, despite its vibrant startup ecosystem and growing venture capital market, lacks a standardised equivalent. While some Finnish startups and investors have explored SAFEs, the instrument has not gained widespread domestic traction. The reason is primarily practical. The SAFE structure, designed for US corporate law, does not align seamlessly with the Finnish Companies Act. Without a standardised and legally sound Finnish adaptation, most market participants continue to rely on familiar instruments such as convertible loans and traditional equity rounds.

In this blog post, we explain what SAFEs are, how they work, why they are difficult to implement in Finland, and how experienced counsel can structure SAFE-like instruments that preserve key benefits while meeting Finnish legal requirements.

How SAFEs work: Key features and differences

SAFE vs convertible loan: What's different?

A SAFE is a standardised agreement through which the investor provides capital in exchange for the right to receive shares upon the occurrence of a triggering event, typically a new funding round, acquisition, IPO, or liquidation.

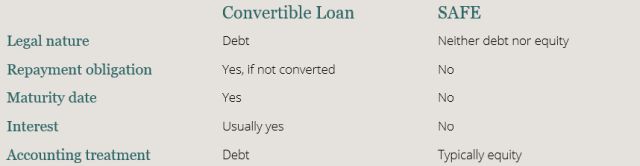

SAFEs are often compared to convertible loans because both convert into equity at a future point. However, the differences are significant:

Because SAFEs have no repayment obligations, maturity date, or interest accrual, they are structurally simpler and operationally more flexible for early-stage fundraising.

Why founders like Safes

For startups, SAFEs offer a fast, cost-effective fundraising tool. They enable swift capital injection without the need to coordinate simultaneous closings or negotiate detailed shareholder agreements. In the United States, legal complexity is typically very low and negotiations focus on commercial terms such as the valuation caps or discounts.

Investor risks and considerations

A defining feature of a SAFE is its open-ended duration. The agreement remains in force until a conversion or liquidity event occurs, potentially staying outstanding indefinitely. This can be acceptable in companies with clear financing trajectories but introduces risk when timelines are uncertain. Investors may face extended periods without liquidity or control rights. As a result, SAFEs may not be suitable for all companies or investors, particularly where a clear path to a financing or exit event is lacking.

Accounting treatment

From an accounting perspective, SAFEs are generally classified as equity instruments, especially where settlement occurs by issuing shares in a future financing round. However, many SAFEs include provisions for cash settlement in a liquidity event. In such cases, the investor typically receives the greater of their original investment, or the amount they would have received had the SAFE converted into equity. Such terms may affect the accounting classification and, depending on the terms and applicable standards, could lead to the instrument being treated as a financial liability rather than equity.

Notably, in Finland, the Accounting Board has concluded ( statement 2032/2022) that a standard SAFE is treated as debt unless its terms are adjusted to remove repayment triggers and align with equity characteristics. This means that, under Finnish Accounting Standards, SAFEs with provisions for cash settlement or repayment obligations cannot be recorded as equity, even though they are commonly viewed as equity instruments in other jurisdictions.

Conversion mechanics: How SAFEs turn into shares

Conversion in a funding round

Regardless of the SAFE variation, conversion into shares during a priced equity round is automatic and irrevocable. This is the most common triggering event. When the company raises funding at a specific price per share, the SAFE automatically converts into shares based on its specific terms. Y Combinator has published three basic variations:

1. SAFE with a discount

The investor receives a discount on the price per share paid by the new investors in the funding round. Example: An investor holds a SAFE for €100,000 with a 20% discount. If new investors pay €10 per share, the SAFE conversion price is €8 per share, and the investor receives 12,500 shares (€100,000 ÷ €8).

The discount compensates the SAFE investor for taking early-stage risk before the company's valuation was established. In practice, these conversion terms are very similar to those used in Finnish convertible loans.

2. SAFE with a valuation cap

A maximum company valuation is set for calculating the investor's conversion price, ensuring a larger equity stake for early investors, if the company's valuation increases significantly. Example: A €100,000 SAFE with a €4 million valuation cap converts in a Series A round priced at €10 million pre-money. The conversion price is calculated as if the company were valued at €4 million, resulting in a lower price per share and more shares for the SAFE investor.

Valuation caps are the most common SAFE structure, as they provide meaningful upside dilution protection for early investors.

3. SAFE with MFN (most favoured nation) clause, no valuation cap, no discount

There is no valuation cap or discount, but an MFN clause allows the investor to adopt more favourable terms offered in later SAFEs.

Conversion in a liquidity event

If the company is acquired or completes an IPO before raising a priced equity round, SAFEs typically do not convert into shares. Instead, the investor receives cash payment equal to the greater of the original investment or the amount that would have been received on conversion at the exit price. This structure ensures the investor participates in the upside if the company exits successfully.

Liquidation and dissolution

If the company is liquidated or dissolved, SAFE holders are paid according to a specific priority. Creditors and debt holders (including convertible loans) are paid first. SAFE holders and preferred shareholders are then paid pari passu (equally). Common shareholders are paid last. This means SAFEs rank senior to common shares but junior to debt in a liquidation scenario.

SAFE alternatives across Europe

Recognising the benefits of SAFE-like instruments, several European countries have developed their own versions adapted to local corporate law:

- United Kingdom (SeedFast): SeedLegals, a legal tech platform, has introduced SeedFAST, an advance subscription agreement that serves as the UK equivalent to SAFEs. SeedFASTs are similar to YC SAFEs and are designed to be compliant with SEIS (Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme) and EIS ((Enterprise Investment Scheme) tax reliefs, making them attractive to UK angel investors.

- Sweden (WISE): The Warrants for Investment in Startups and Enterprises (WISE) is a warrant-based instrument that mimics a perpetual convertible loan. It is treated as equity on the balance sheet. WISE is designed specifically for Swedish limited liability companies (Aktiebolag).

- Norway (SLIP): In Norway, Startuplab, in collaboration with its law firm SANDS, has launched the Startup's Lead Investment Paper (SLIP), an equity instrument tailored for Norwegian startups.

- France (BSA AIR): Bon de Souscription d'Actions – Accord d'Investissement Rapide), published by French legal professionals, is the French equivalent of the SAFE, allowing investors to subscribe for future shares of the company at the next equity round.

- Germany (KISS): The Keep It Simple Security (KISS) is a standardised agreement similar to the YC SAFE, adapted to German legal requirements.

Each of these instruments demonstrates that whilst the SAFE concept has clear benefits, it requires careful adaptation to local legal frameworks. Across Europe, local adaptations can be complex, as each country must tailor the instrument to its own legal system. Even in the United States, recent updates to SAFE agreements, such as changes to liquidation preferences and side letters, have added further complexity to the original model. Finland has yet to develop an industry-wide equivalent, but the tools exist within Finnish corporate law to create similar structures.

Why SAFEs are hard to implement under Finnish law

Using the original Y Combinator SAFE agreements directly in Finland creates several legal, tax, and accounting challenges. Finnish corporate law does not recognise SAFEs as a distinct instrument category, creating uncertainty about whether they would be treated as debt, equity, or contracts.

Contractual conversion rights in a loan agreement are not securities under Finnish law and may only give rise to breach-of-contract claims rather than enforceable property rights. The tax treatment of SAFEs is also uncertain under Finnish tax law, potentially creating unexpected consequences for both companies and investors. Finally, determining whether a SAFE should be classified as equity or a financial liability under Finnish accounting standards (FAS or IFRS) is not straightforward.

These uncertainties mean that using an unmodified SAFE in Finland creates legal risk. Modifying the SAFE to comply with Finnish law, however, often requires additional legal resources, undermining the original purpose of simplifying fundraising.

How to build SAFE-like instruments in Finland

Despite these challenges, Finnish corporate law offers several tools that can be combined to create SAFE-like instruments. The Finnish Companies Act includes provisions for various financing instruments that, when structured carefully, can replicate many SAFE features .

Capital loans and convertible capital loans

Finnish limited liability companies can issue a capital loan (pääomalaina), which has equity-like characteristics, if conditions under the Companies Act are met. The defining feature of a capital loan is that repayment is only allowed if the company has sufficient distributable equity.

Capital loans rank above equity but below ordinary debt in bankruptcy. If structured without a maturity date and without repayment triggers, a capital loan can even be booked as equity, similarly to how SAFEs are typically treated.

A company may issue a convertible capital loan that is perpetual (no maturity), interest-free and convertible based on discount, valuation cap, or MFN clauses. If properly structured, such an instrument mimics key SAFE features: counted as equity, no maturity date, and conversion terms similar to SAFEs.

However, implementing SAFE-like conversion terms under Finnish law raises enforceability challenge. In jurisdictions where SAFEs are well-established, they are recognised as securities, granting holders enforceable rights to conversion or exit proceeds. In Finland, contractual conversion rights in a loan agreement are not securities and only give rise to breach-of-contract claims if the company fails to honour them. In practice, this enforceability risk can be mitigated by additional agreements, such as requiring existing shareholders to commit to honouring the conversion terms. Whilst this approach strengthens the investor's position, it adds administrative burden, as all shareholders must participate in these side agreements.

Strengthening enforceability through subscription warrants

To address the enforceability concern more robustly, companies can utilise subscription warrants (option rights to the company's new shares) that qualify as securities under Finnish law. Subscription warrants offer stronger legal protection than purely contractual conversion rights and can be structured in several ways to achieve SAFE-like economics.

The first approach would be to issue standalone subscription warrants without any convertible loan component. This means that the investor pays an option premium upfront (the actual investment), receiving warrants that entitle the investor to subscribe for shares at a future date based on predetermined terms. The option premium is treated as equity under Finnish law, meaning that no debt component exists. Under current law, shares would need to be issued at a nominal subscription price (e.g. €0.01 per share) when warrants are exercised, though the Finnish Companies Act is currently proposed to be amended to allow shares to be issued pursuant to subscription warrants at zero price, which would more accurately replicate the SAFE structure.

Alternatively, subscription warrants could be attached to convertible capital loans, where the loan agreement provides that the company issues warrants allowing investors to subscribe for new shares at a discount or capped valuation in future rounds or liquidity events. In this structure, the loan principal can be used to pay the subscription price when warrants are exercised.

Regardless of the structure, subscription warrants must be publicly registered with the Finnish Trade Register, creating a public record of the investor's rights. This registration requirement is the trade-off for the stronger legal enforceability that warrants provide compared to purely contractual arrangements.

Comparing the two approaches

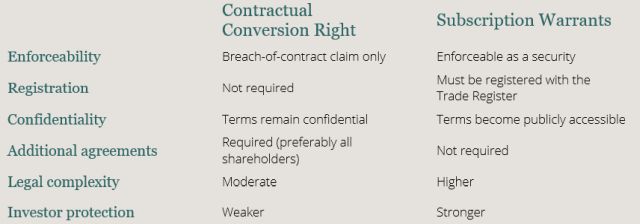

Both structures can achieve SAFE-like outcomes, but with different trade-offs:

The choice between these approaches depends on the specific circumstances. Subscription warrants offer stronger legal enforceability and are often preferred by professional investors who prioritise legal certainty. However, contractual conversion rights may be more suitable for companies with few shareholders, where the administrative burden of side agreements is minimal and the benefits of confidentiality and flexibility outweigh the enforceability concerns.

Practical hurdles in creating SAFE-like instruments

Both approaches – contractual conversion rights and subscription warrants – come with trade-offs. Contractual conversion rights avoid registration requirements and keep terms confidential, but they require shareholder agreements to ensure enforceability. This can be cumbersome in companies with many shareholders and adds administrative complexity.

Subscription warrants, while offering stronger legal protection, introduce their own practical challenges. The primary technical hurdle is determining the number of shares issued upon conversion. Because subscription warrants must comply with the Finnish Companies Act and be registered with the Trade Register, Finnish law requires precision in share issuance terms at the time of registration. This can be difficult to reconcile with SAFE-style valuation caps and discounts that depend on future funding round terms not yet known at the time of issuance. The proposed amendments to the Finnish Companies Act would address some of these concerns, building on the already significant flexibility of Finnish corporate law to further facilitate creation of SAFE-type instruments.

Confidentiality is another consideration. Subscription warrants must be registered with the Trade Register, making the terms publicly accessible. This contrasts with contractual SAFEs in other jurisdictions, which typically remain confidential between the parties. For companies and investors who prefer to keep investment terms private, this public disclosure requirement may be a disadvantage.

Finally, both structures require planning for future corporate changes. Convertible capital loans and subscription warrants are not shares before conversion, so they do not entitle holders to dividend distributions or repayment of invested equity prior to conversion. Finnish companies relatively commonly reorganise their corporate structure through legal mergers, demergers, spin-offs and share exchanges. Each of these transactions would require corresponding adjustments to the SAFE terms to ensure the investor's rights are preserved. This challenge is not unique to Finland. Even in the US, the SAFE terms do not necessarily address corporate reorganisations which is why SAFEs work best in startup companies that do not plan major structural changes before the anticipated conversion event.

These factors mean that creating SAFE-like instruments under Finnish law requires legal effort and documentation, which conflicts with the SAFE's original goal of simplicity. However, with experienced counsel, the complexity can be managed and the resulting instrument can still offer meaningful benefits compared to traditional financing structures.

Pragmatic solutions for Finnish startups

While SAFEs offer elegant, flexible financing in the United States and several European countries, Finnish corporate law presents structural challenges that complicate their direct use. Nevertheless, these challenges are not insurmountable.

With the support of experienced legal counsel familiar with both SAFE mechanics and Finnish corporate law, Finnish startups and investors can structure instruments that closely resemble SAFEs, preserving many of their key benefits such as simplicity, flexibility, and equity treatment. Though some compromises and legal work are required, these solutions can often be implemented at moderate cost and with manageable complexity.

The upcoming amendments to the Finnish Companies Act are expected to further facilitate these structures, bringing Finnish law closer to the flexibility that makes SAFEs work so well elsewhere.

As the Finnish startup ecosystem continues to grow and internationalise, there is also potential for industry-wide collaboration to develop a standardised, legally sound SAFE-like instrument tailored to Finnish law. Such an initiative would bring the best of global practices into the local context, benefiting founders, investors, and the broader venture capital ecosystem.

For now, the path forward requires balancing the SAFE's elegant simplicity with the realities of Finnish corporate law. With the right legal expertise, that balance is achievable, allowing Finnish startups to access the same fundraising flexibility that their international counterparts enjoy

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]