- in European Union

- in European Union

- within Media, Telecoms, IT and Entertainment topic(s)

- with readers working within the Law Firm industries

This is the background I would like to share: my firm, Schweiger & Partners, has received overwhelmingly positive public feedback.

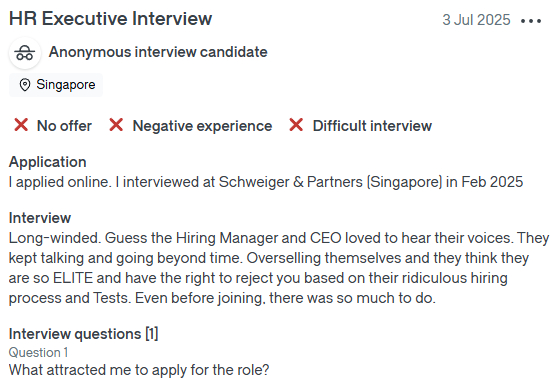

Not long ago, a candidate who didn't make it through our hiring process left a public review on Glassdoor. In it, they described our interviews as "long-winded" and accused us of being "elitist." They felt we talked too much, expected too much, and made the hiring process unnecessarily intense.

We read it. We reflected on it. And ultimately — we agreed.

Yes — our process is long.

Yes — we hold ourselves to elite standards.

That is because we do not hire to fill chairs.

We hire to win.

We're building a high-performance team, not a comfort zone. And we make no apology for designing a process that filters for what we call Class A team members — people who not only thrive under pressure but actively seek it out because they care deeply about the quality of their work.

My article here is not a rebuttal. It is an explanation.

I will be sharing:

- Why our hiring process is built the way it is

- How we extract real behavior — not just interview performance

- What you can learn from it, whether you're a candidate, a hiring manager, or just curious about what it takes to build an elite team

Because if one candidate publicly misunderstood our standards, it's likely others are silently wondering the same. And we would rather clarify now — and attract the right kind of applicants — than lower the bar later.

What We Are Truly Looking For: Class A Individuals

We are not looking for someone who can simply do the job.

We are looking for someone who can do the job better than

we imagined — someone who raises the standard,

speeds things up, and inspires others to level up.

We call them Class A players.

These are not people with perfect CVs or charming interview styles. They are people who:

- Deliver independently — without constant reminders or management babysitting

- Improve systems, not just follow them

- Think in business outcomes, not just tasks

- Spot problems before they surface

- Take ownership for more than their job description

- Make other team members faster, calmer, and smarter

This kind of person is rare. They are not common in the job market because they are not often available. And they are not easy to identify — because you cannot see them clearly from a CV, a personality test, or a friendly chat on Zoom.

That is why we do not run "friendly chats".

We observe carefully what we see. We look at reveal

behavior under load — where clarity, pressure, and

accountability collide.

Because we have learned something the hard way:

A single wrong hire can cost far more than a delayed hire.

And a single Class A hire can change the entire trajectory of a

team.

So we filter hard. And we filter honestly.

The goal is not to impress anyone. It is about finding the people

who want to be measured — because they know they will pass

the test.

Why Personality Tests Alone Do Not Identify Class A Individuals

It can be tempting to believe that with the right tools — such as personality assessments, cognitive evaluations, or motivational profiling — it is possible to automate the search for top-level talent.

However, this assumption does not align with how high performance actually functions.

Class A performance is not a fixed trait.

It is a behaviour.

And behaviour only becomes visible under specific conditions.

An individual may appear calm in a quiet, controlled setting,

but may lose composure in a chaotic environment.

They may describe themselves as proactive — until they are

asked to build a system from the ground up with minimal

guidance.

They may achieve a high score for conscientiousness — but

still fail to complete a project without receiving several

reminders.

This is why we do not rely solely on standardized testing to identify exceptional individuals.

I am repeating myself, but I also realize that I cannot make the following statement often enough:

"You cannot find Class A people with a personality test — it is behavioural."

To elaborate: the same individual can demonstrate Class A performance in one environment but behave like a Class C performer in another. This variation depends on several contextual factors, including:

- The system they are placed into

- The clarity of expectations

- The degree of accountability present

- Their genuine level of motivation for the work itself

For this reason, our hiring process is not focused on assessing

personality traits (although we look at them carefully).

Instead, it is designed to simulate actual working conditions and

to observe real responses.

We want to understand how individuals behave when the situation is unclear, fast-paced, demanding, and grounded in real tasks.

This is the nature of our daily work environment.

It is also the context in which the most capable individuals

consistently excel.

Our Systems Approach: Hiring with an Engineering Mindset

If Class A behavior cannot be identified through a résumé or standardised test, then how can it be detected?

The answer is to build a system.

We approach hiring in the same way an engineer would design a high-performance machine. The goal is not to predict results based on assumptions, but to observe how a system behaves over time under specific conditions.

An Internal Analogy: Hiring as System Modelling

When modeling dynamic systems using differential equations, three main factors determine behaviour. We apply this same logic to our hiring process.

1. Type of System

- In Engineering: The system may be linear or nonlinear, time-invariant or time-varying. These characteristics define how it will respond to input.

- In Hiring: This refers to the nature of the work environment.

Our environment is nonlinear, fast-paced, and feedback-driven. Success in this context does not come from following fixed procedures. It requires solving new problems daily while maintaining stable operations elsewhere.

An individual who thrives in slow-moving, highly structured organizations may struggle in our setting, regardless of how strong their credentials appear on paper.

2. System Parameters

- In Engineering: Parameters include constants such as gain, resistance, and damping, which influence how the system performs.

- In Hiring: These are individual capabilities,

such as:

- Previous performance

- Speed of learning

- Communication style and clarity

- Emotional resilience

- Decision-making under stress

We evaluate these through structured interviews and by collecting references from former colleagues and managers. However, strong parameters alone are not enough. Performance also depends on context and starting point.

3. Initial Conditions

- In Engineering: These are the values known at the start of the model. They strongly influence initial system behaviour.

- In Hiring: These are the statements and commitments made by the candidate at the beginning of the process.

This includes how candidates describe themselves, what they claim they will deliver, and how they say they respond to pressure, feedback, conflict, and complexity.

These initial claims are critical — because they will be tested.

For example:

- If a candidate claims to be proactive, we will ask what they intend to deliver within their first 90 days.

- If they claim to perform well under pressure, we will look for such behaviour in real time.

We do not evaluate identity or personality in isolation.

We evaluate observable behaviour — under real pressure in our

daily work as a team.

This is the only reliable way to distinguish between a genuine Class A contributor and someone whose strengths exist only in theory.

How We Obtain Clear Commitments from Candidates

Once we have created a structured evaluation environment — including realistic pressure, limited time, and relevant context — our goal is not to identify clever or polished answers.

Our goal is to obtain commitments.

The only reliable way to identify a Class A performer is to ask what they intend to do — and then observe whether they follow through on that commitment.

We use two primary methods to extract these commitments:

First Method: The Proactivity Test

This is not a personality test.

It is a structured exercise designed to prompt candidates to

describe how they intend to behave in real-world scenarios.

We ask questions such as:

- What do you do when no one checks your work?

- How do you act when given unclear instructions?

- What is your default response when a task falls outside your formal responsibilities?

We do not assign scores to these answers.

Instead, we record them as a behavioural baseline.

Approximately six months later, during the probation review, we refer back to these statements and ask:

Did this person act in accordance with what they originally described?

This process is not intended to expose inconsistencies.

It is designed to identify candidates who understand professional

accountability.

We are seeking individuals who say, in effect:

Evaluate me based on my actions, not merely on my intentions.

Second Method: The Best-Self Declaration

This method is based on our internal leadership practices and is

also described in our public materials.

We ask each candidate to respond to the following four prompts:

- The one thing I am better at than most is...

- If I were to underperform in the first six months, it would most likely be because...

- What I want to be held accountable for during my first 90 days is...

- This is how I will know I am doing a good job...

These questions require candidates to think clearly.

They reveal whether the individual is capable of reflection,

strategic thinking, and honest self-assessment.

These statements also function as "initial

conditions."

By asking candidates to define their own standards explicitly, we

remove ambiguity and invite genuine commitment.

If a candidate truly meets the standard of a Class A contributor, they will welcome this process.

The Case Study: Why One Strong Candidate Failed Our Process

Recently, a candidate applied for a remote Human Ressources (HR) Executive role at our firm. On paper, he was qualified — in fact, more than qualified by conventional standards.

He had:

- A PhD (pending viva) in Leadership & Organisational Behaviour

- Teaching experience in HR management and strategic planning

- Managerial experience in education and food & beverage

- Publications in peer-reviewed journals

He made it through the early filters and was invited for interviews — including a session with me, the CEO.

But during the process, something became clear: while he had credentials, he lacked alignment with the core behavior we seek.

- He struggled with the intensity of the process.

- He viewed structure as a burden.

- He questioned the legitimacy of our standards.

And after being rejected, he posted a public review on Glassdoor calling us "long-winded" and "elitist."

We are not naming him here to embarrass anyone.

We are sharing this because it illustrates something important:

A strong CV and years of experience are not the same as Class A performance.

In fact, in this case, his background included strategic-level work in a government-linked institution, which ignores our internal hiring warning for public-sector decision-makers applying for private-sector leadership roles.

That warning was missed early — but his behavior during interviews reconfirmed it:

- He expressed discomfort with accountability-driven processes.

- He rejected the idea that he should be measured beyond his résumé.

- He viewed a structured, multi-stage interview as a power play — not as a fair filter.

He didn't fail because he wasn't capable. He failed because he didn't want to be tested. And for us, that's the test.

It's not personal. It's operational.

Our environment is designed for people who crave performance

tension — not those who fear it.

And strangely, his Glassdoor review was a gift.

It proved our system did exactly what it was supposed to do:

Filter out the misaligned before the damage is

done.

The Probation Period: The Six-Month System Test

Making it through our hiring process does not mean that you have

"arrived."

It means that you have been given access to the real test:

your work.

At my firm Schweiger & Partners, probation is not a grace period. It is a structured system test — designed to observe whether a new hire actually behaves like the person they promised to be.

The Six-Month Arc

- Month 1–2: You receive onboarding, context, and clear expectations.

- Month 3–4: You begin to take ownership of your area — we expect momentum to build.

- Month 5–6: You are fully in motion. And this is where we evaluate.

At Month 5, we ask:

Are they delivering what they said they would — in behavior, outcomes, and initiative?

We go back to their:

- Proactivity Test

- Self-assessment declaration

- Interview statements

This is not meant to "catch" anyone.

It's to measure integrity between stated

intent and actual performance.

At the End of Month 6, We Ask Two Questions:

1. Can they demonstrate the value of their work — in terms of money?

We expect clarity around:

- What did you deliver?

- Who did it help?

- What amount of money did it earn, directly or indirectly?

Whenever possible, we ask for monetary framing:

- Did your work produce money by generating extra revenues?

- Can we quantify the outcome?

We are not asking for fluff.

We are asking for evidence.

2. Can they do the work 1st class — without external support?

We look at:

- Are they executing at a professional standard — without reminders?

- Do they need handholding from a co-worker?

- Do they require frequent oversight from a manager?

If the answer is no — if they are driving, not riding

— they pass.

If not, we part ways — respectfully, but clearly.

Because by Month 6, if someone still cannot self-manage, they are not in the right place.

And that is okay — we all win by knowing early.

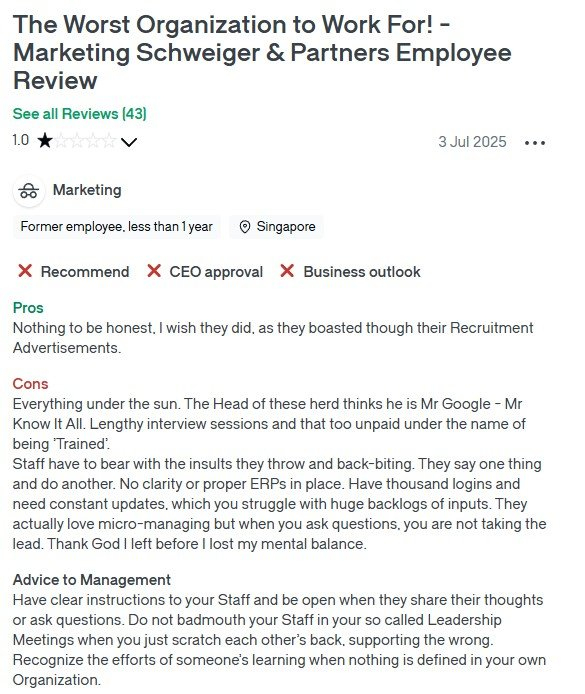

A Second Case Study: When Probation Works Exactly as Intended

We recently terminated another hire during probation —

this time from our marketing team.

The individual had passed the initial interviews and was

enthusiastic at the start. But as the weeks progressed, key

misalignments became clear.

They struggled with:

- Managing our structured systems and task infrastructure

- Accepting feedback constructively

- Delivering work independently and on time

- Understanding that learning curves are normal, but performance still matters

When expectations weren't met, the response wasn't

ownership — it was emotional projection.

They described our structured processes as

"micro-managing."

They misunderstood feedback loops as "insults."

And after being terminated, they left a public review accusing us

of being disorganized, unsupportive, and mentally

destabilizing:

We won't dissect their language — it speaks for

itself.

But what it proves is something more important:

The system did its job.

Probation exists not to "weed out the weak" but to protect both sides:

- For the company: from onboarding someone who drains speed, energy, or clarity

- For the individual: from committing long-term to a system they are not built for

We do not expect perfection during probation.

We expect behavioral growth, professional

communication, and a clear match between the promises

someone makes... and how they show up when things get complex.

This particular employee failed that test.

And while we regret that the experience was negative for them, we're proud that our process surfaced the mismatch early — and gave them the freedom to find something better aligned elsewhere.

This is our rationale for taking up new members into our team as described here:

Because if we do not say "no" at Month 3 or Month 6, we end up saying "why" at Month 12.

Why We Will Not Lower Our Standards — Now or in the Future

We recognise that our hiring process is not suitable for

everyone.

It requires time. It demands transparency. It often places

candidates in situations that are uncomfortable.

This is not a flaw. It is a deliberate filtering mechanism.

We are building a highly specific type of team:

One that operates on the principles of clarity, discipline, and

accountability.

If we compromise these principles — even once — the

entire system begins to decline.

This decline has predictable consequences:

- Standards begin to fall

- Motivation and momentum decrease

- High performers choose to leave

We have observed what happens when organisations lower their

standards "just this once."

They encounter internal friction.

They spend excessive management time supporting

underperformers.

They lose operational speed — not because the individuals are

inherently incapable, but because those individuals were not

suitable for the role or the environment.

We are therefore unambiguous on this point:

We would rather lose 10 "maybe" candidates than hire 1 wrong one.

Our Guiding Principle

- Every candidate we decline represents a success — if that decision protects the integrity of the team.

- Every candidate we accept must contribute beyond their own role. They must amplify team performance, not require constant oversight.

- Every team member must provide clarity. None should create confusion.

This is why we are not discouraged when someone describes our

process as "too demanding."

For the right individuals, it does not feel excessive.

For the right individuals, it demonstrates that we approach people

— and performance — with seriousness and respect.

And that is precisely the kind of team they are seeking to join.

Final Note: Why Class A Individuals Value This Process

We do not expect every candidate to value our hiring

process.

In fact, we expect that many will not.

This is intentional.

Class A individuals — the type of professionals we are building our organisation around — are not searching for convenience.

They do not resent being tested.

They welcome it — because they know the test

protects their future teammates from mediocrity.

They do not need comfort.

They need clarity.

They want to know:

If I go all in here, will I be surrounded by others doing the same?

Our hiring process is how we prove that the answer is "yes".

Call-to-Action: A Formal Invitation

If you consider yourself a Class A professional, and:

- You take full ownership of your responsibilities

- You perform best under clear, direct expectations

- You want your work to produce measurable results

- You expect to be held to the same high standards you apply to others

Then we encourage you to apply.

However, we ask that you do not submit a résumé on its own.

Come with a promise. And be ready to keep it.

Because that is how we hire.

And that is how we win.

IP Lawyer Tools by Martin Schweiger

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.