- with Inhouse Counsel

- in United Kingdom

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit and Retail & Leisure industries

Economic shifts, regulatory changes and market disruptors like AI are injecting additional uncertainty and fuelling conflict in transactions

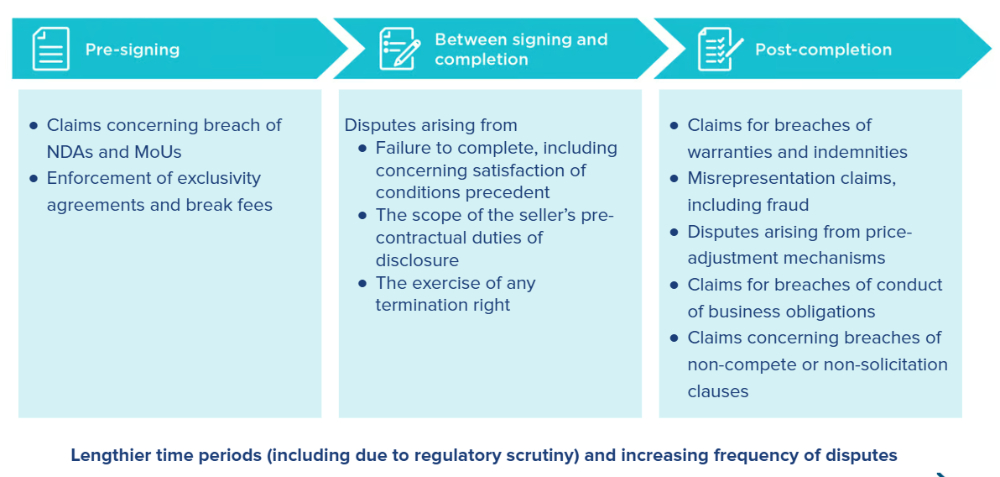

We expect the heightened disputes risk we have seen in recent years to continue in 2026. Volatile market dynamics, shifting regulatory environments and geopolitical uncertainties, as well as market disruptors such as the energy transition and AI, are all contributing to an uncertain deal-making environment, fuelling the potential for conflict. However, parties can take steps to minimise these risks.

Pre-signing phase

Getting to a deal is an art in itself – it is taking longer to agree deals in a volatile and changing market. Lengthier negotiation periods mean more time for relationships to falter and disagreements to derail the deal. Dealmakers should therefore prepare for uncertainty and challenges even at the pre-signing phase. While confidentiality has always been important, we anticipate more disputes on the grounds of breach of NDAs, especially where deals in the technology and energy sectors require disclosure of sensitive information. If sellers have their heads turned, buyers are more likely to enforce exclusivity agreements and to pursue any break fees.

Between signing and completion

Once the deal is signed, the focus shifts to achieving completion. Conditions precedent and gap-period risks are common sources of disputes.

Geopolitical and macroeconomic risks are seen as potential deal breakers, with buyers nervous about exposure to resulting business volatility in the period between signing and closing. The prolonged interim periods between signing and closing caused by increased FDI screening and other regulatory scrutiny mean there is more time for any execution risk to play out.

As a result, far more attention is given by both buyers and sellers to measures that allocate risk during this time, such as warranty bring-downs, material adverse change clauses and other termination rights, and more scrutiny is placed on compliance with pre-closing covenants on conduct of business.

MAC clauses – the approach in different jurisdictions

A material adverse change or MAC condition is intended to protect a buyer from an adverse change in the relevant business before completion of the transaction.

This type of clause is very common in public company transactions, though less so in private deals, other than in the US, where such clauses are typical in both public company and private transactions.

They vary from transaction to transaction but tend to require there to have been an "event" or other change which has an adverse financial consequence. That could be defined in very general terms or defined by reference to a quantified impact on the earnings or net assets of the business.

A key issue is whether, in any given situation, the buyer will be able to rely on the clause.

In the US, MAC conditions are typically defined in general, conceptual terms based on the effect an event or occurrence has on the business and its financial condition and results, with exceptions for a range of matters that broadly affect the economy or an industry in a manner that is not specific to the target business. While such clauses are included in nearly all acquisitions (both public and private), the standard for proving a MAC is exceptionally high. Under Delaware law (the most common governing law for acquisition agreements in the US), courts have consistently held that the effect must be "material when viewed from the longer-term perspective of a reasonable acquirer" and must be "durationally significant", with temporary or transient impacts being insufficient to trigger the MAC condition. Only one buyer in Delaware history (Fresenius Kabi AG, in its proposed acquisition of Akorn, Inc., a specialty generic pharmaceutical company) has ever successfully triggered a MAC condition, and in that transaction the target business suffered more than a 50% decline in EBITDA (with no reason to expect a rebound) while at the same time experiencing "overwhelming evidence of widespread regulatory violations and pervasive compliance problems". Although each state in the US will have a slightly different approach to deciding cases invoking MAC conditions, the standard for triggering such a condition will be similarly high in each state.

While terminating an acquisition on the basis of a MAC clause is unlikely in the US in all but the most extreme scenarios, US buyers have successfully sought to terminate transactions due to material breach of interim operating covenants. The risk of such a breach increases as the time between signing and closing, together with market and geopolitical volatility, increase. Buyers and sellers should be clear about what the seller is permitted to do to respond to changing circumstances between signing and closing, and sellers should proceed carefully before taking actions outside of the ordinary course of business during the interim period between signing and closing.

In Australia, there has been renewed interest in these clauses following the high-profile dispute between Mayne Pharma and Cosette Pharmaceuticals. In that case, Cosette had agreed to purchase Mayne Pharma under a scheme of arrangement transaction. The agreement included a MAC condition which would be triggered if there was an event that had an adverse impact on Mayne Pharma's earnings (subject to a number of exceptions). Two months after the transaction was agreed, Mayne Pharma, having experienced lower sales revenue, issued a profit downgrade. Cosette claimed that the lower sales, together with some other issues, constituted a MAC and purported to terminate the transaction. The dispute ended up in court. Mayne Pharma won as Cosette was unable to show that there had been a relevant change which had caused the loss. It was not enough that Mayne Pharma had lowered its profit forecast.

There are a number of lessons to be learned from this, including:

- The threshold for proving a MAC is high and depends on the specific drafting of the clause.

- A buyer cannot rely solely on missed financial forecasts to establish a MAC, particularly where forecasts are accompanied by disclaimers.

- A forecast variance is not itself a MAC, but is rather evidence of an adverse change. It is necessary to show a change in the actual position as distinct from a change between a forecast and an actual position.

- A buyer wishing to protect itself from lower sales would be better off including specific conditions relating to sales revenue pre-completion.

Another issue in Australia is who determines whether there has been a MAC in a public company transaction. Most significant public company transactions in Australia are conducted by scheme of arrangement which are supervised by the courts, so the natural course of action is to test a MAC claim in the court, as occurred in the Mayne Pharma/Cosette transaction. However, whilst this gives rise to a detailed and certain consideration of the issue, litigation is a time-consuming process which may not fit well in a deal timetable. There is now a question in Australia whether a MAC dispute in a public transaction should be considered by the Takeovers Panel, which is usually much faster than the courts in its decision-making. That would make Australia's approach like the approach in the UK.

In the UK, a condition to a takeover can only be invoked with the consent of the UK Takeover Panel and so it is the Takeover Panel that decides whether there has been a MAC. The threshold for invoking any condition on a takeover in the UK is high, but even higher for a MAC where a bidder has to demonstrate that the relevant circumstances are of "very considerable significance striking at the heart of the purpose of the transaction". This was tested shortly after the start of the Covid-19 pandemic where a bidder sought to invoke a MAC in April 2020 because of the impact of the pandemic, and related UK Government measures, on the target, Moss Bros. The Panel did not allow the condition to be invoked. The arguments and reasoning were not made public, but it is likely that the fact that the takeover offer was announced the day after the World Health Organisation declared Covid-19 to be a pandemic, and that the target directors had cited the potential for uncertainty caused by Covid-19 in their reasons for recommending the offer, had a bearing on the Panel's decision.

Post-completion

Completion marks finalisation of the deal, but after the ink dries, the risks don't disappear. Disputes post-completion are also on the rise, be they claims for breach of warranties or indemnities, misrepresentation claims, or disagreements over price adjustments, particularly when the purchased assets have not met performance expectations.

Trending issues such as ESG, AI and cybersecurity are leading to an increase in the breadth of warranty packages, particularly for businesses in the environmental, energy and technology sectors – providing extra scope for post-completion claims.

As limitations on liability for breach of warranty may preclude or reduce an otherwise valid claim, claims for fraudulent misrepresentation are also on the rise. A fraud claim, while harder to establish, may provide a route to uncapped liability and therefore an increased measure of damages.

In addition, parties have increasingly utilised earn-outs and other forms of contingent consideration to bridge valuation gaps in the midst of market volatility, and these mechanisms (especially earn-outs) are notorious for giving rise to potential disputes. Any time a seller does not achieve an earn-out, there is likely to be some level of dispute about the way the business was operated and managed following closing, whether or not such dispute ultimately leads to full blown litigation or arbitration. To mitigate these risks, buyers and sellers must seek to be clear in establishing goals that align their interests in achieving the earn-out targets, as no amount of contractual protections will help parties who have misaligned interests.

Potential for disputes across stages of a deal

Strategies to mitigate disputes

There are, however, a number of strategies which the parties to a transaction can adopt to seek to reduce the possibility of a dispute, or to deal with a dispute successfully should one arise:

- As well as relying on representations and warranties, buyers should conduct thorough due diligence, including on ESG and AI risks.

- Sellers should ensure a comprehensive disclosure exercise and have a strategy in place for dealing with any known issues (ideally before these are raised by the buyer).

- Comprehensive W&I insurance is becoming a must-have for sellers, who are required to provide a growing array of warranties, and for buyers who do not wish to take counterparty credit risk – but it is no substitute for proper diligence, and there may be gaps in coverage.

- Key deal terms must be drafted with precision. Clear methodologies in purchase price adjustment mechanisms and earn-out formulas can materially mitigate the risk of disputes post-completion.

- Parties should use well-drafted dispute resolution clauses to avoid difficulties in bringing claims and to ensure enforceable outcomes.

- A proactive approach to dispute management can often lead to a quicker and less contentious resolution.

- In the event of a dispute, parties should develop a robust strategy early on, including thinking creatively about strategies to achieve favourable outcomes, such as considering injunctive relief – our HSF Kramer Decision Analysis tool can create a financial model of probable outcomes to assist decision-making and settlement discussions.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.