- within Corporate/Commercial Law topic(s)

- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Finance and Tax Executives

- in European Union

- in European Union

- in European Union

- with readers working within the Accounting & Consultancy, Advertising & Public Relations and Banking & Credit industries

The Indian startup ecosystem has entered a new phase of maturation. For multiple decades, start-up entrepreneurs moved their holding structures offshore, to United States, Singapore, or Mauritius, seeking access to foreign capital, building international credibility, better exit opportunities and simplified stock option frameworks. In many cases, it was simpler to issue employee stock options to employees under these foreign regimes. Additionally, raising capital in United States dollars helped companies avoid currency exchange problems, thereby facilitating international valuations and exits. Furthermore, multiple startups wanted to list their shares on foreign stock exchanges or sell their companies to international buyers.

During the first half of the 2010s, having a parent company abroad seemed to make dealing with regulations easier, gave the company a more global image, and helped complete deals faster. For companies selling software services, financial technology, or advanced technology across borders, this overseas setup made commercial sense during their growth phase. However, the equation has fundamentally shifted. The very offshore structures that once enabled rapid growth are now, in many cases, creating friction. They are increasingly constraining further expansion, complicating capital access, and posing challenges for companies seeking to list on public markets.

With India's public markets outperforming most global exchanges, regulatory frameworks being rationalised, and a genuine domestic IPO pipeline emerging, an increasing number of companies are evaluating whether their offshore holding company still serves its original purpose. As a result, many of these companies are now actively considering bringing their corporate structures back to India.

Against this backdrop, reverse flipping has emerged as a strategic business decision. Companies are pursuing reverse flips to unlock better valuations, prepare for public listings in India, facilitate investor exits, and build long-term operational sustainability. For founders, CFOs, and growth-stage investors, the decision to reverse flip is increasingly driven by commercial and strategic considerations rather than regulatory compulsion alone.

This article examines the commercial rationale, strategic benefits, structuring options, regulatory and tax considerations, and the evolving role of reverse flipping in India's maturing startup ecosystem.

Reverse Flipping: Meaning and Commercial Rationale

Reverse flipping is a process which involves companies which were incorporated outside of India shifting their legal domicile and headquarters back to India. This process involves the transfer of ownership and control from a foreign holding company to an Indian entity. It effectively reverses the earlier "flipping structure" adopted by Indian startups that had incorporated their parent companies abroad.

Contrary to popular belief, reverse flipping is not primarily driven by nationalist intents, but by practical commercial considerations and regulatory convenience. Some common reasons why companies are inclined towards reverse flipping are as follows:

Leveraging Advantages offered by Indian Capital Markets: India is leading in terms of capturing a significant share of global IPO activity. There is extremely high demand from both retail and institutional investors. This high demand pushes IPO prices up, supporting higher valuations and consequently incentivising companies to reverse flip their structure and list themselves in Indian markets.

Economic and Market Opportunities: Companies whose products, services and operations are primarily targeted towards the Indian audience want to capitalize on India's growing consumer market and rising incomes. Additionally, the increasing favorability of Indian regulations, including supportive government policies, start-up schemes, and tax incentives, provides further reason to shift domicile back to India.

Simplified Group Structure: Another major reason companies are undertaking reverse flipping is to simplify their group structure and form a unified business structure, rather than having multiple entities. This helps in ensuring a simple corporate structure and eliminate duplicate corporate procedures. A notable example of this is Pepperfry, which unified its complex group structure through the reverse-flipping mechanism, involving inbound merger via the NCLT route and a domestic merger, resulting in a single main Indian holding entity, "Pepperfry Private Limited".

Cost and structural complexity: Maintaining offshore structures can be expensive and cumbersome. Offshore structures require annual renewals, foreign audits, multi-jurisdictional tax filings, and compliance with local corporate laws. While these costs made sense when raising capital abroad, they often outweigh the benefits for companies that no longer rely on offshore funding.

Structuring a Reverse Flip

The reverse flipping structure can be achieved primarily through the following structures:

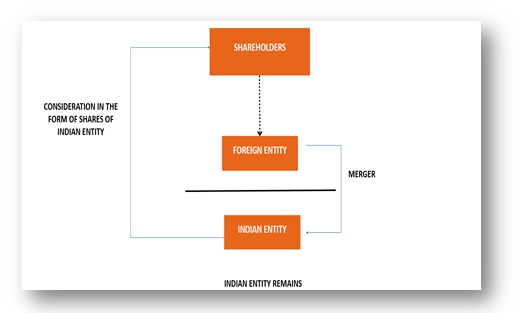

Inbound merger: In an inbound merger, the foreign holding company merges into its Indian subsidiary. Post-merger, the resultant company is the Indian entity, which becomes the ultimate parent company, and the foreign shareholders receive shares of the resultant Indian company. This can be done through the following ways:

- NCLT Route: This inbound merger process can be implemented through the NCLT route under Section 234 of the Companies Act, 2013 ("Act"), Rule 25A of the Companies (Compromises, Arrangements, and Amalgamations) Rules, 2016 ("CAA Rules") and the Foreign Exchange Management (Cross-Border Merger) Regulations, 2018 ("Cross Border Merger Regulations"). The NCLT route is time-consuming and can take anywhere between 7 to 14 months to complete, depending on the jurisdiction in which the foreign entity is located. Several companies undertook reverse flipping using this route including Pepperfry, Meesho, Pine Labs, and Zepto.

- Fast Track Merger Route: The Ministry of Corporate Affairs introduced sub-rule 5 to Rule 25A of the CAA Rules on September 9, 2024, effective from September 17, 2024. The amendment permits an inbound merger between a foreign company with its wholly owned subsidiary through the fast-track merger route provided under Section 233 of the Companies Act, 2013. This route substantially reduces the timelines and can be completed within an estimated 3-4 months.

Below is a diagrammatic representation of an Inbound Merger Structure:

REVERSE FLIPPING STRUCTURE (INBOUND MERGER)

RESULTING STRUCTURE

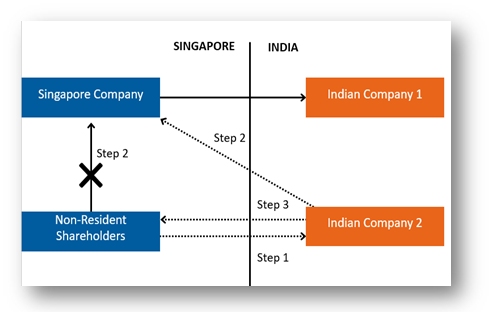

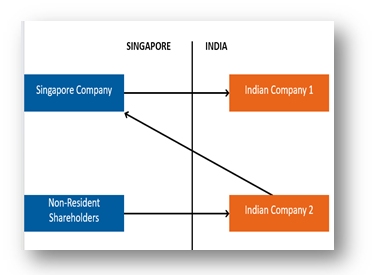

Share swap: In this structure, shareholders of the foreign holding company (referenced in the below diagram as "Singapore Company") incorporate a new Indian company (referenced in the below diagram as "Indian Company 2") (Step 1), which acquires all shares of the foreign holding company from the shareholders of the foreign holding company (Step 2) and in-turn issues its own shares as consideration (Step 3). As a result, shareholders hold shares in the new Indian company, which is the parent entity, and the foreign holding company becomes its wholly owned subsidiary, which in turn owns 100% of existing Indian company (referenced in the below diagram as "Indian Company 1").

Below is a diagrammatic representation of a Share Swap Structure:

REVERSE FLIPPING STRUCTURE (SHARE SWAP)

RESULTANT STRUCTURE

RBI Approval for Inbound Mergers: Under the Cross Border Merger Regulations, cross-border mergers require RBI approval. However, Regulation 9 of these Cross-Border Merger Regulations provides for deemed approval if the merger complies with prescribed conditions, including sectoral caps, pricing guidelines, entry routes, and reporting requirements. This deemed approval requirement is extremely clear when inbound mergers proceed through the NCLT route. However, confusion arises when one contemplates whether such relaxation is also applicable to inbound mergers undertaken through the fast-track merger route. In this regard, Rule 25A(5) of the CAA Rules 2024 amendment states that both companies (foreign holding company and its wholly owned subsidiary) "shall obtain the prior approval of the Reserve Bank of India." However, it is worth noting that if there is RBI deemed approval in the case of NCLT-driven inbound mergers, then what practical reasons restrict its applicability to inbound mergers driven by the fast-track merger route? In this regard, it's important that the regulators provide absolute clarity, considering the increasing prevalence of fast-track reverse flipping mergers and their critical importance from a transaction-timelines perspective.

Composite Mergers via the Fast-Track Merger Route: Another complex question, for which there is little to no clarity or precedent, is whether composite mergers can take place under the fast-track merger route. The Act permits composite schemes under Sections 230–232 (NCLT route), wherein a single scheme can include multiple restructuring steps, such as an inbound merger followed by a domestic merger or a demerger of a business division. However, whether such composite schemes can be implemented through a fast-track merger route is still unclear. Ideally, if each limb of the composite scheme independently can be executed through a fast-track merger route, a composite scheme as a whole should be permissible. However, in the absence of any regulatory clarity, a conclusive answer cannot be reached, and further clarification from regulators should be awaited.

Key Considerations for Reverse Flipping

Compliance with Foreign Exchange Laws: Issuance or transfer of securities to non-residents through inbound mergers or otherwise must adhere to the pricing guidelines, entry routes, sectoral caps, attendant conditions and reporting requirements for foreign investment as laid down under Foreign Exchange Management (Non-Debt Instruments) Rules, 2019. Additionally, a reverse flip may result into the entry of foreign investors in India, companies should therefore assess the applicability of Press Note 3 to each of their foreign investors.

Other regulatory and sectoral approvals: Depending on the nature of the business, the transaction may require sector-specific regulatory approvals, including approvals relating to changes in control, ownership, shareholding and management of the entity. The need to notify or obtain approval from the Competition Commission of India (CCI) as a result of the internalisation will also have to be assessed. Additionally, compliance with the laws of the jurisdiction where the foreign holding company is incorporated must be examined.

ESOPs: ESOPs originally granted by the offshore entity to employees who transition to the Indian company will need to be reworked to align with Indian legal requirements, which typically involves the Indian company issuing fresh employee stock options. Where the Indian company grants ESOPs to non-resident employees, directors or officers, such grants will be subject to the Foreign Exchange Management (Non-Debt Instruments) Rules, 2019, including compliance with applicable entry routes, sectoral caps, conditions and reporting obligations. Further, a mandatory one-year cliff applies from the date of grant before options can vest, which may result in delays in vesting or exercise following internalisation. These restructuring requirements and regulatory constraints may, in practice, impact employee sentiment and could lead to dissatisfaction or attrition, particularly among key managerial personnel and directors, where there is a perceived dilution in incentives or changes to the economic value or terms of existing options.

Conclusion

Reverse flipping marks a significant evolution in India's startup ecosystem. What was once a regulatory workaround has now become a strategic financial tool for unlocking higher valuations, deeper liquidity, and stronger domestic capital participation. For founders, it represents a return to the home market with global ambitions intact. For investors, it offers improved exit reliability and alignment with India's expanding public markets. For employees, it increases the likelihood of real liquidity through domestic listings. Most importantly, reverse flipping reflects India's emergence as a self-sufficient startup capital market and no longer dependent on foreign jurisdictions to legitimise growth. As India's IPO pipeline deepens and institutional capital expands, reverse flipping is poised to become a mainstream feature of the startup lifecycle rather than an exception.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.