- within Cannabis & Hemp and Insolvency/Bankruptcy/Re-Structuring topic(s)

In this article, the authors first briefly review the basic elements of the False Claims Act (FCA) and its qui tam provisions, and recent Department of Justice (DOJ) enforcement statistics. They then discuss a number of FCA developments, including: (1) the aftermath and impact of the Supreme Court decisions in United States ex rel. Polansky v. Executive Health Resources, Inc.,1 and United States ex rel. Schutte v. SuperValu, Inc.;2 (2) the Supreme Court's expansion of FCA liability to claims made to private-public funded programs in Wisconsin Bell, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Heath;3 (3) the Trump administration's FCA goals, strategies, and approaches; (4) legislative changes to existing FCA laws; and (5) continuing FCA enforcement focus and scrutiny on the opioid crisis, COVID-19 pandemic-related fraud, and cybersecurity measures.

I. BASIC ELEMENTS OF THE FCA AND QUI TAM PROVISIONS

The Civil False Claims Act (FCA)4 was enacted in 1863 in response to allegations of fraud in Civil War procurements. The FCA has since become the government's weapon of choice to combat fraud, waste, and abuse in government contracting. The FCA makes it unlawful for a person to knowingly: (1) present or cause to be presented to the government a false or fraudulent claim for payment, or (2) make or use a false record or statement that is material to a claim for payment.5 A person acts "knowingly" under the FCA if he or she acts with "actual knowledge, deliberate ignorance or reckless disregard of the truth or falsity of information."6 Mistakes and ordinary negligence, however, are not actionable under the FCA.7

The FCA provides for up to treble damages and as of January 15, 2025, penalties of between $14,308 and $28,619 per violation. Violators are also subject to administrative sanctions, including potential suspension, debarment, or program exclusion from participating in government contracts. The FCA has a lengthy statute of limitations of no less than six years and, in some cases, up to 10 years after a violation has been committed.

The FCA permits private citizens, known as qui tam relators, to bring cases on behalf of the government. In qui tam cases, the complaint and a written disclosure of all relevant evidence known to the relator must be served on the U.S. Attorney for the judicial district of the court where the case was filed as well as on the U.S. Attorney General. The qui tam complaint is then ordered sealed for a period of at least 60 days, and the government is required to investigate the allegations contained therein and decide whether to intervene. If the government declines to intervene, the relator may proceed with the complaint on behalf of the government. The complaint must be kept confidential and is not served on the defendant until the seal is lifted. Relators may receive a "whistleblower bounty" of between 15 and 25 percent of the recovery if the government intervenes in their cases and between 25 and 30 percent if the government declines.

II. DOJ REPORTS MORE THAN 1,400 NEW FCA CASES AND BILLIONS OF DOLLARS IN RECOVERIES

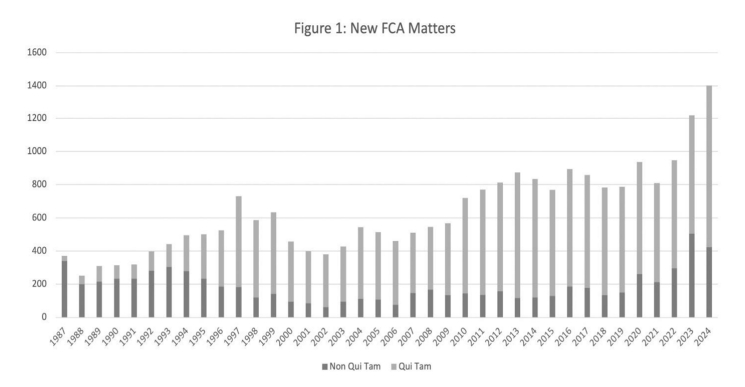

Figure 1 charts new FCA cases per year, which shows a steady increase in qui tam-driven cases.8 Well over 700 FCA cases have been filed each year for the past 15 years and a high percent of those cases have been qui tam cases. Many qui tam cases remain under seal for years pending the DOJ's intervention decision. In 2024, there was a high-water mark in new FCA cases brought by both the government and qui tam relators for a total of 1,402, with the highest number of new qui tam actions, 979, both likely linked to the expenditure of substantial federal funds related to pandemic relief and the ever increasing budgets tied to federal healthcare and other procurement programs. This uptick started back in 2020 during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and related federal stimulus. In the past four years, the government also filed more new FCA cases per year than in prior years, showing the FCA remains a high priority for enforcement.

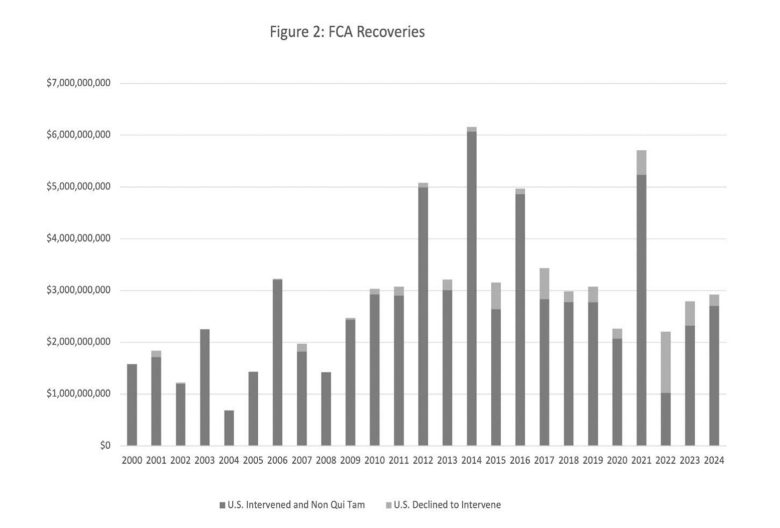

The DOJ collected over $2.9 billion in settlements and judgments in 2024, a slight increase from 2023 FCA monetary recoveries of $2.68 billion, but still trending downwards from prior years when there were more individual big settlements. Nonetheless, in 2024, DOJ pulled in 558 settlements and judgments, the second highest number in a single year after last year's record of 566. Figure 2 shows annual recoveries by the government in FCA cases and compares recoveries coming from qui tam cases where the government declined to intervene versus non-qui tam cases or qui tam cases where the government intervened.9 Consistent with recent trends, DOJ reported recoveries ($1.67 billion) in 2024 mostly came from settlements and judgments from the healthcare industry, including managed care providers, hospitals, pharmacies, pharmaceutical companies, laboratories, long-term acute care facilities, and physicians. DOJ reported that additional 2024 recoveries reflected its focused attention on new enforcement priorities such as pandemic-related fraud and cybersecurity requirements in government contracts and grants.

III. THE AFTERMATH OF THE SUPREME COURT DECISIONS IN POLANSKY AND SCHUTTE

A. The Government Exercising Its Broad Dismissal Authority Under 31 U.S.C. § 3730(c)(2)(A)

FCA Section 3730(c)(2)(A)10 allows the government to dismiss a qui tam action over the objection of the relator. Rarely used until recent years, § 3730(c)(2)(A), significantly backed by the Supreme Court's decision in United States ex rel. Polansky v. Executive Health Resources, Inc.,11 has now emerged as a more frequent method of ending qui tam FCA cases. In Polansky, the Supreme Court (in an 8-1 majority decision) affirmed the government's authority to dismiss qui tam actions whenever it chose to intervene during the litigation, whether at the outset or a later time in the case. The Supreme Court also held that in assessing such a dismissal motion, district courts should apply the rule generally governing voluntary dismissal of suits in ordinary civil litigation, Rule 41(a). Though district courts must evaluate whether the dismissal occurred on "proper" terms, which requires weighing the relator's interests against the government's interests, the Supreme Court expressly recognized that the government will satisfy Rule 41 "in all but the most exceptional cases" and that deference should be given to the government's views (once it has intervened). To meet the standard for Rule 41, the government need only offer a reasonable argument for why the burdens of continued litigation outweigh its benefits (e.g., grounds for why the case is not likely to prevail and arguments related to significant litigation and discovery costs). This is so even if the relator presents compelling counterarguments.

In the wake of Polansky, the government has secured several dismissals in the FCA context, facing little to no resistance from the courts in implementing its broad dismissal authority under § 3730(c)(2)(A).12 This slew of recent decisions illustrates the government's dismissal muscle, allowing it to intervene and seek dismissal with confidence at any stage of a qui tam litigation, fully aware that the courts accept that the threshold for doing so is low.

Moreover, while Polansky confirmed that a § 3730(c)(2)(A) motion affords a qui tam relator an "opportunity for hearing," courts have nonetheless granted dismissals based solely on the parties' written submissions, without holding a separate hearing.13 In Vanderlan, the district court emphasized that Polansky only required the government to offer a reasonable argument for why the burdens of continued litigation outweigh its benefits, with the term "argument" not mandating discovery or an evidentiary hearing. Moreover, the Vanderlan court concluded that the requirement for a relator to have an "opportunity to be heard" could be satisfied through briefing, submitted exhibits and/or oral arguments. In August 2024, the Fourth Circuit cemented this interpretation when in U.S. ex rel. Doe v. Credit Suisse AG14 it held that § 3730(c)(2)(A) does not require any in-person "hearing." The majority opinion provided three reasons for its holding:

- The Second Circuit and several district courts have determined written submissions met the hearing requirement;

- The Fourth Circuit and other courts have found the term "hearing" has a "fluid" meaning not limited to live proceedings; and

- Polansky confirmed that the government is entitled to substantial deference in its decision to dismiss an action.

Thus far, no relator has successfully demonstrated, in a published opinion, that their case is "exceptional" enough to overcome a government's § 3730(c)(2)(A) motion to dismiss. And, it is clear that the government is increasingly willing to pursue such dismissal if and when it chooses, including after years of costly litigation and discovery expenses borne by the relators. This growing trend may have some chilling effect on suits brought by relators. In light of the DOJ's string of published wins in this area, relators and their counsel should seriously assess the likelihood of a case's success as they gather evidence and be prepared to demonstrate the case's potential to prevail without overburdening the government to prevent a dismissal.

Footnotes

1 United States ex rel. Polansky v. Executive Health Resources, Inc., 599 U.S. 419 (2023).

2 United States ex rel. Schutte v. SuperValu, Inc., 598 U.S. 739 (2023).

3 Wisconsin Bell, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Heath, No. 23-1127 (U.S. Feb. 21, 2025).

4 31 U.S.C. § 3729 et seq.

5 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729(a)(1)(A)–(B) (2009); U.S. ex rel. Rose v. Stephens Inst., 909 F.3d 1012, 1017 (9th Cir. 2018).

6 31 U.S.C. § 3729(b).

7 United States v. Sci. Applications Int'l Corp., 626 F.3d 1257 653 F. Supp. 2d 87 (D.D.C. 2009).

8 DOJ Office of Public Affairs, Fraud Statistics—Overview (January 15, 2025), available at https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/media/1384546/dl.

9 Id.

10 "The Government may dismiss the action notwithstanding the objections of the person initiating the action if the person has been notified by the Government of the filing of the motion and the court has provided the person with an opportunity for a hearing on the motion."

11 United States ex rel. Polansky v. Executive Health Resources, Inc., 599 U.S. 419 (2023).

12 See e.g., U.S. ex rel. USN4U v. Wolf Creek Federal Services, No. 1:17-cv-0558 (N.D. Ohio Dec. 7, 2023); U.S. ex. rel. Sargent v. McDonough, No. 1-23-cv-00328-LEW (D. Me. Feb. 27, 2024); U.S. ex rel. Vanderlan v. Jackson HMA, LLC, No. 3:15-CV-767-DPJ-FKB (S.D. Miss. Apr. 12, 2024); U.S. ex rel. Hill v. Ernst & Young U.S., LLP, No. 1:23-CV-319 (E.D. Va. Mar. 4, 2024); U.S. ex rel. Guglielmo v. Leidos, Inc., No. 1:19-CV-1576 (D.D.C. Feb. 20, 2024), and U.S. ex rel. Relator LLC v. Dayhoff, No. 0:23-cv-60292-KMW (S.D. Fla. Apr. 30, 2024).

13 See e.g., U.S. ex rel. Vanderlan v. Jackson HMA, LLC, No. 3:15-CV-767-DPJ-FKB (S.D. Miss. April 12, 2024) (dismissal granted without any discovery or evidentiary hearing); and U.S. ex rel. USN4U v. Wolf Creek Federal Services, No. 1:17-cv-0558 (N.D. Ohio Dec. 7, 2023) (dismissal granted without any hearing).

14 U.S. ex rel. Doe v. Credit Suisse AG, 117 F.4th 155, 162 (4th Cir. 2024).

To view the full article click here

Originally published by Lexis Nexis

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.