- within Corporate/Commercial Law topic(s)

- in South America

- within Corporate/Commercial Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Oil & Gas industries

- within Wealth Management, Antitrust/Competition Law and Transport topic(s)

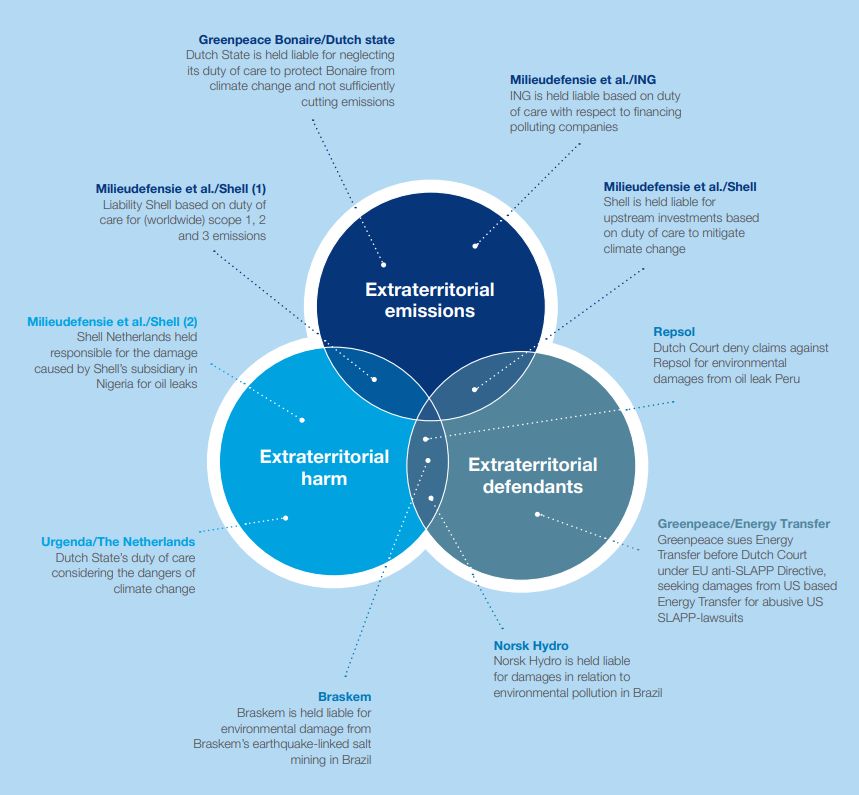

1. In our previous trend report, we identified the trend of climate change litigation is shifting from targeting states to also targeting companies. Such climate change litigation is often based on the duty of care to protect against dangerous climate change, considering the enforcement of human rights. This trend has continued in 2024 and 2025. Recent law further crystalised the specifics of the duty of care of states and companies in relation to fighting dangerous climate change. This provides for further clarity on what to expect from states and companies, for example in terms of mitigation and/or adaptation measures.

In the Annex to this trend report we will discuss several recent ESG litigation cases – both from Dutch courts and international courts – that shed further light on how climate change obligations of companies and states are being enforced through civil litigation.

2. Recent cases, including Bonaire and Nitrogen, illustrate the Dutch courts' proactive stance in enforcing specific obligations under the general duty of care of states, focusing on particular geographical areas and types of emissions. The Shell I-case demonstrates that the transition from a general duty of care of companies to specific reduction obligations remains challenging due to regulatory complexities and market dynamics (please be referred to our Shell I-case analysis).

The efforts of interest organization Milieudefensie in both the Shell II-case and the ING-case will potentially be a next step in terms of corporate liability and specific duties of care in ESG matters.

3. Dutch courts have also shown increasing receptiveness for environmental claims, also in cases with crossborder dimensions. In the Norsk Hydro-case, the District Court of Rotterdam accepted jurisdiction over claims concerning environmental pollution in Brazil, recognizing the legal standing of a Brazilian association under Dutch law. Similarly, in the Braskem-case, the District Court of Rotterdam held the Brazilian parent company liable for damages caused by an earthquake linked to its salt mining activities in Brazil, underscoring the willingness of Dutch courts to hold foreign companies accountable through their Dutch subsidiaries. In other cases, courts take a more critical stance towards environmental claims against foreign companies. While the District Court of The Hague accepted jurisdiction over the Dutch subsidiary in the Repsol-case, the court declined jurisdiction over the Spanish parent and Peruvian subsidiary due to insufficient factual and legal connection with the claims against the Dutch subsidiary.

4. In this context, the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the KlimaSeniorinnen ruling by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) provide further guidance (please see our publications on both the advisory opinion and the ECHR's ruling here and here). Both confirm that states have specific obligations to prevent climate-related harm, based on international and human rights law. The ICJ's advisory opinion and the KlimaSeniorinnen ruling by the ECHR offer important guidance on states' climate obligations under international and human rights law. While the ICJ's opinion is non-binding, it affirms a duty of due diligence and rejects the "drop in the ocean" defence, confirming that even minor contributions to global emissions may entail legal responsibility.

The binding KlimaSeniorinnen ruling further establishes that insufficient climate action can breach positive obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights (the Convention). Both decisions clarify that states must not only act directly but also enact effective legislation to ensure that private actors – including both companies as individuals – contribute to climate mitigation and adaptation.

5. We have also seen a rising trend of anti-ESG movements (please be referred to our earlier blog on this here). This phenomenon, though more prominent in the USA, is also emerging in Europe and the Netherlands, be it in a more moderate form. For example, since Q4 2024, European legislators have been negotiating the simplification of the CSDDD (the so-called 'Omnibus', please be referred toour publication on this and on the most recent Omnibus developments here). Despite emerging anti-ESG challenges, the trajectory of ESG litigation suggests continued growth, driven by the need to address environmental and social governance issues. In the coming years, the outcomes of the Shell II-case and the ING-case in first instance and the Shell I-case in cassation will provide further clarity on which specific obligations can be required and demanded of companies in specific cases, ultimately shaping the future landscape of ESG litigation and demonstrating the practical challenges in enforcing such obligations.

ESG litigation in the Netherlands: key cases and emerging trends

Annex: Relevant climate change litigation

1. Climate change litigation in the Netherlands against the Dutch State

1.1 Bonaire-case

In January 2024, Greenpeace representing the interests of the people of Bonaire, along with eight Bonaire residents (together: Greenpeace et al.), initiated civil law proceedings under the Act on Collective Damages in Class Actions (Dutch acronym: WAMCA) against the Dutch State (the Bonaire-case). According to Greenpeace et al., the Dutch State fails in its duty of care towards (specifically) the people of Bonaire by not taking sufficient measures to protect the people of Bonaire from the effects of climate change and therefore not adequately limiting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to meet the targets of the Paris Agreement.

On 25 September 2024, the District Court of The Hague ruled on the admissibility of Greenpeace et al. The court ruled that Greenpeace itself met all the admissibility requirements and therefore found Greenpeace's claim admissible. With the summons issued against the Dutch State in this case, Greenpeace Netherlands has not only brought claims on behalf of the population of Bonaire; the same claims have also been brought by eight individuals on their own behalf. As for the claims of these individuals, the court decided that Greenpeace already sufficiently represents their interests collectively. Since a class action is more efficient and effective than pursuing individual claims, the court considered that the class action proceedings are not suitable to also decide on individual claims and ruled that the individual claimants are inadmissible. The hearing on the merits will take place early October 2025.

The Bonaire-case is clearly similar to the Urgenda-case, as both concern the Dutch State's duty of care considering the dangers of climate change. However, the Bonaire-case focuses on a more specific situation and set of claims. The claimants in the Bonaire-case focus on the particular dangers of climate change for the inhabitants of the small island of Bonaire, who are allegedly especially vulnerable to its consequences. Moreover, the declarations sought by the claimants in the Bonaire-case are more concrete than those in the Urgenda-case, as they pertain to clearly defined adaptation and mitigation measures, tied to specific percentage targets.

1.2 Nitrogen-case

In another class action initiated by Greenpeace against the Dutch State, Greenpeace claimed that the Dutch State acted unlawfully by failing to take sufficient measures to reduce – specifically – nitrogen deposition in Natura 2000 areas below critical deposition values (the Nitrogen-case, please be referred to our earlier publication on this). Greenpeace sought a declaratory judgment that the Dutch State was not meeting statutory nitrogen targets for 2025 and 2030 and requested the court to order the State to bring certain percentages of these areas below the applicable standards by 2025 and 2030, with a penalty payment for non-compliance. The Dutch State argued that it was the legislator's role, not the court's, to determine necessary measures and highlighted ongoing efforts to reduce nitrogen deposition. We have seen a similar line of the defence from the Dutch State's side in for example the Urgenda-case. This case too has some similarities with the Urgenda-case, but is more specific, from a geographical point of view (because it relates to specific vulnerable areas within the Netherlands) and from a legal point of view (because the claims are based on more specific European legislation).

On 22 January 2025, the District Court of The Hague ruled that the Dutch State had not taken sufficient measures to prevent the deterioration of nitrogen-sensitive nature in Natura 2000 areas, and it failed to meet statutory nitrogen targets. The court found that the Dutch State acted unlawfully and ordered it to comply with the 2030 nitrogen target, prioritizing the most vulnerable nature areas. The court imposed a one-time penalty of EUR 10 million if the target was not met, reflecting a lack of confidence in the Dutch State's voluntary compliance.

2. Climate change litigation against states before the European Court of Human Rights and international developments

2.1 KlimaSeniorinnen-case

On 9 April 2024, the ECHR rendered judgments in three climate change litigation cases, against Switzerland, Portugal (and 32 other European states) and France. All three cases concerned the legal question whether the Convention entails a state's duty of care to protect the human rights of its inhabitants by reducing GHG emissions. The claims of the applicants were primarily based on the positive obligations of states to protect the right to life (Article 2 of the Convention) and the right to respect for private and family life (Article 8 of the Convention). The ECHR only decided on the merits in the case against Switzerland (the KlimaSeniorinnen-case), as it declared the other two cases (against Portugal and France) inadmissible.

The ECHR ruled that Switzerland failed to act in a timely, adequate and consistent manner with respect to the design, development and implementation of the relevant legislative and administrative frameworks to prevent (dangerous) climate change. Therefore, Switzerland did not meet its obligations under Article 8 of the Convention, which protects the right to private and family life and thus violated the human rights of the KlimaSeniorinnen association by failing to take adequate measures against climate change (please see our blog for an overview of further implications of the KlimaSeniorinnen-case and the notable fact that the KlimaSeniorinnen association was held admissible before the ECHR).

2.2 Müllner-case

After exhausting all national remedies, with the final decision from the Austrian Supreme Court communicated on 12 October 2020, Austrian citizen Mr. Müllner with temperature-dependent multiple sclerosis (MS) filed a case before the ECHR against the Austrian government on 25 March 2021 (the Müllner-case). Mr. Müllner claims that the government's failure to implement effective climate measures to reduce GHG-emissions violates his (individual) human rights under Articles 8 and 13 of the Convention, because higher temperatures exacerbate his MS symptoms, causing significant distress, and that Austrian law does not provide an effective remedy for challenging administrative omissions and legislative inaction on climate issues.

On 18 June 2024, the ECHR notified the Austrian government of the application and requested their observations. The ECHR granted the case priority status, due to the urgency and importance of the issues raised, and the alleged deterioration of Mr. Müllner's health due to global warming.

This case differs from the KlimaSeniorinnen-case and all other aforementioned climate change litigation, because it involves an individual claimant with specific health issues significantly affected by climate change, rather than a specific group (being the KlimaSeniorinnen association or the residents of the island Bonaire). This highlights the direct impact of climate change on an individual and its personal health and, consequently, on its (very personal) human rights.

This Müllner-case could set a significant precedent by recognising personal, individual harms from climate change as human rights violations, potentially influencing future climate litigation and prompting stronger climate policies. Mr. Müllner's unique and personal situation highlights the immediate and severe effects of climate change on individual health, which may pave the way for both more robust legal frameworks to address climate-related human rights issues, and the possibility of future liability claims for inadequate climate policies (as set out regarding the Bonaire-case).

2.3 ICJ's advisory opinion

On 23 July 2025, the ICJ issued its advisory opinion on the obligations of states under international law to address climate change (please be referred to our update on this here). The advisory opinion was requested by the UN General Assembly, following a global initiative led by Vanuatu and supported by over 130 states. The ICJ clarified that states have binding obligations to prevent significant environmental harm, including through the regulation of private actors, and that failure to do so may trigger international legal responsibility.

The ICJ held that states must act with due diligence, adopting proactive legislative and administrative measures based on the best available science. These obligations apply not only to state conduct but also to emissions caused by private actors (such as companies) within their jurisdiction.

Importantly, the ICJ found that breaches of these obligations constitute internationally wrongful acts, giving rise to duties of cessation, non-repetition, and full reparation. The ICJ also rejected the so-called "drop in the ocean" defence, affirming that even small contributions to global emissions can result in legal responsibility if they contribute to cumulative climate harm. Furthermore, the ICJ rejected the autonomy of private actors as a defence of states.

Although the ICJ's opinion is not legally binding, it carries significant persuasive authority and may influence future climate litigation, including cases against both states and companies. The opinion reinforces the growing legal consensus that climate inaction can amount to a breach of international (human rights) law and may support the development of more robust legal frameworks for climate accountability.

3. Climate change litigation against companies in the Netherlands

3.1 Shell I-case

In 2019, the Dutch NGO Milieudefensie and other individual claimants (Milieudefensie et al.) initiated a class action against Shell, ordering that Shell must reduce its GHG emissions by 45% by 2030, based on Dutch tort law and human rights obligations (the Shell I-case). In May 2021, the District Court of The Hague ruled that Shell has a duty of care to mitigate its contribution to dangerous climate change and was therefore required to reduce its GHG emissions by 45% by 2030, based on 2019 levels (we refer to our earlier trend report on this here). The court ruled that Shell has a 'result obligation' with respect to the Shells group GHG emissions (Scope 1 and Scope 2) and a 'best-efforts obligation' for its suppliers and customers (Scope 3).

In the long-awaited ruling in the Shell I-case in appeal of 12 November 2024, the Court of Appeal of The Hague acknowledged the human rights implications of climate change. The court confirmed that EU regulations require companies to prepare climate transition plans consistent with the EU's climate objectives. This could entail a general duty of care for (large) companies to mitigate climate change. However, the court did not impose specific reduction targets on Shell, because of regulatory complexities and market dynamics. For example, the existing EU regulation does not mandate specific, sectoral GHG reduction targets for individual companies. This lack of specific – and sectoral – legal requirements influenced the court of appeal's decision not to impose a concrete reduction obligation on Shell following from its (existing) general duty of care to mitigate climate change.

The outcome of the Shell I-case (for now, Milieudefensie et al. lodged cassation on 12 February 2025 and consequently the case will now be heard by the Dutch Supreme Court) highlights the hurdles of ESG litigation against companies, emphasizing the balance between legal obligations and practical considerations in the global market. Milieudefensie et al. lodged an appeal against the judgment of the Court of Appeal, so the case will now be handled by the Dutch Supreme Court.

3.2 Shell II-case

In its ruling in the Shell I-case, the Court of Appeal the Hague suggests a path for new climate change litigation focused on preventing future emissions by aiming to block specific investment plans rather than addressing past emissions. This indicates that the legal framework for banning such investments may already be developing. The court emphasises the need to consider how fossil fuel investments can create a 'lock-in effect,' where significant initial investments in fossil fuel infrastructure commit resources for the long term, delaying the energy transition. This reflects the court's recognition that mere investment strategies may not be effective in achieving GHG emission reductions without concrete regulatory frameworks or commitments.

On 13 May 2025, Milieudefensie announced the initiation of new legal proceedings against Shell (Shell II-case), seeking a court order to halt Shell's investments in new, undeveloped oil and gas fields. The ruling of the Court of Appeal of The Hague in the Shell I-case basically functioned as a catalyst for this litigation, with the objective of targeting 'lock-in' fossil fuel investments: Milieudefensie's claim is founded on the court's recognition that such investments risk undermining the energy transition and may constitute a violation of Shell's legal duty of care. By focusing on upstream investments and the concepts of carbon and institutional lock-in effects, Milieudefensie aims to translate the court's general findings into specific, enforceable obligations. The Shell II-case aims to directly restrict corporate (upstream) investment strategies that are not aligned with climate objectives. Following Shell's response on 13 June 2025, Milieudefensie confirmed its intention to proceed with serving the writ of summons, thereby formally initiating the Shell II-case.

3.3 Norsk Hydro-case

In 2021, a Brazilian association initiated a proceeding (not being a class action under the WAMCA) against Norsk Hydro ASA and its Dutch subsidiaries, regarding cross-border corporate liability in relation to environmental pollution in Brazil (Norsk Hydro-case).

On 19 October 2022, the District Court of Rotterdam established jurisdiction over Norsk Hydro ASA, as the company did not contest jurisdiction due to the presence of its Dutch subsidiaries. In its interim ruling of 29 May 2024, the court ruled that the Brazilian association and nine individual claimants were admissible to bring claims in the Netherlands. The court found that the association had legal personality under Brazilian law and met the requirements of Dutch procedural law. Since the proceedings were not a class action under Dutch law, the specific admissibility criteria for class actions did not apply. The court thus accepted the claims as admissible, illustrating the willingness of Dutch courts to handle ESGrelated claims, even when the alleged environmental harm occurred abroad (in this case, in Brazil).

A hearing on the merits took place on 12 March 2025. A final judgment on the merits is currently expected in September 2025.

3.4 Braskem-case

In 2022, a resident of Maceió, Brazil, initiated legal proceedings in the Netherlands against Braskem S.A., a Brazilian petrochemical company, concerning crossborder corporate liability for environmental damage allegedly caused by Braskem's salt mining activities, which are linked to a local earthquake (the Braskem-case). On 21 September 2022, the District Court of Rotterdam established jurisdiction to rule on the claims against Braskem due to its Dutch subsidiaries. In its ruling of 24 June 2024, the court ruled that Braskem is liable for the damages caused by the earthquake.

Both the Norsky Hydro-case and the Braskem-case underscore the responsibility of companies with a Dutch connection for their environmental and social impacts abroad. Furthermore, they both demonstrate the receptiveness of Dutch courts to hear cases against foreign companies based on the actions of their Dutch subsidiaries and to hold parent companies accountable for their subsidiaries' conduct, particularly in ESG matters.

3.5 Repsol-case

Another noteworthy case is the class action proceedings initiated against the Spanish parent company of Repsol and Dutch and Peruvian subsidiaries of Repsol, a Spanish multinational energy and petrochemical company (the Repsol-case).

On 21 May 2025, the District Court of The Hague determined its jurisdiction over three Repsol entities in relation to an oil spill incident in Peru. While the court acknowledged the legitimacy of the claims brought against the Dutch Repsol subsidiary, it determined that the evidence linking these claims to those against the Spanish parent company and the Peruvian subsidiary was insufficient to establish a sufficient connection. The court concluded that the claims were not based on the same facts or legal grounds, and that there was no risk of conflicting judgments. Consequently, the court ruled that it had no jurisdiction to rule on the claims against the foreign Repsol entities.

3.6 ING-case

Milieudefensie filed a lawsuit against ING on 28 March 2025, demanding the bank to halve its total GHG emissions by 2030 and to continue reducing them in line with scientific recommendations (the ING-case). A key aspect of Milieudefensie's claims focuses on ING's Scope 3 emissions. Scope 3 emissions include indirect emissions resulting from the activities financed by the bank, such as loans to and investments in companies that use or produce fossil fuels. Milieudefensie argues that ING – as (financial) facilitator – has considerable influence over the economy and contributes to GHG emissions through financing activities. The question under consideration is whether ING has such an enforceable duty of care as a 'facilitator' towards companies, as those in the fossil fuel sector, which are responsible for a 'lock-in effect' (as mentioned in the Shell I-case).

Milieudefensie furthermore asserts that ING is breaching its duty of care – inter alia based on human rights – by failing to take adequate measures to reduce its Scope 3 emissions. This duty of care has been confirmed in the aforementioned Shell I-case, in which the Court of Appeal in The Hague determined that large companies must reduce their GHG emissions to prevent dangerous climate change. Despite this obligation, ING has not implemented sufficient climate measures, which Milieudefensie claims to be in violation of the law. Milieudefensie has made several demands of ING. Firstly, the bank must establish absolute reduction targets for its Scope 3 emissions. Secondly, it must cease financing new fossil fuel projects. However, Milieudefensie also asserts that ING must reduce its Scope 3 emissions in eight specific polluting sectors that ING finances (such as the steel and aviation sectors), in accordance with the reduction pathways of the International Energy Agency's Net Zero Emissions scenario.

Moreover, Milieudefensie introduces the concept of dynamic absolute sectoral reduction targets. Milieudefensie argues that these targets are necessary to address the challenge highlighted in the Shell I-case, where the court ruled that a fixed reduction percentage cannot be imposed because reduction scenarios are subject to (scientific) updates. Dynamic targets allow for adjustments based on the latest scientific data and sector-specific circumstances, ensuring that companies remain accountable while adapting to new information and evolving standards.

Milieudefensie's approach demonstrates a clear evolution in their strategic approach, evidenced by the implementation of a procedure that aligns with the specific nuances of various claims within various sectors and that also accounts for the continuous developments in climate science and therefore also sectoral standardization.

A notable aspect of this evolution is the Milieudefensie's acknowledgement of lessons learned from the precedent set by the Shell I-case, in which the Court of Appeal concluded that that mandating an absolute reduction obligation upon Shell was unfeasible due to the flexibility of the established standard, which could not be adequately applied across the oil sector.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.